Compiler Optimizations: From Source Code to Fast Machine Code

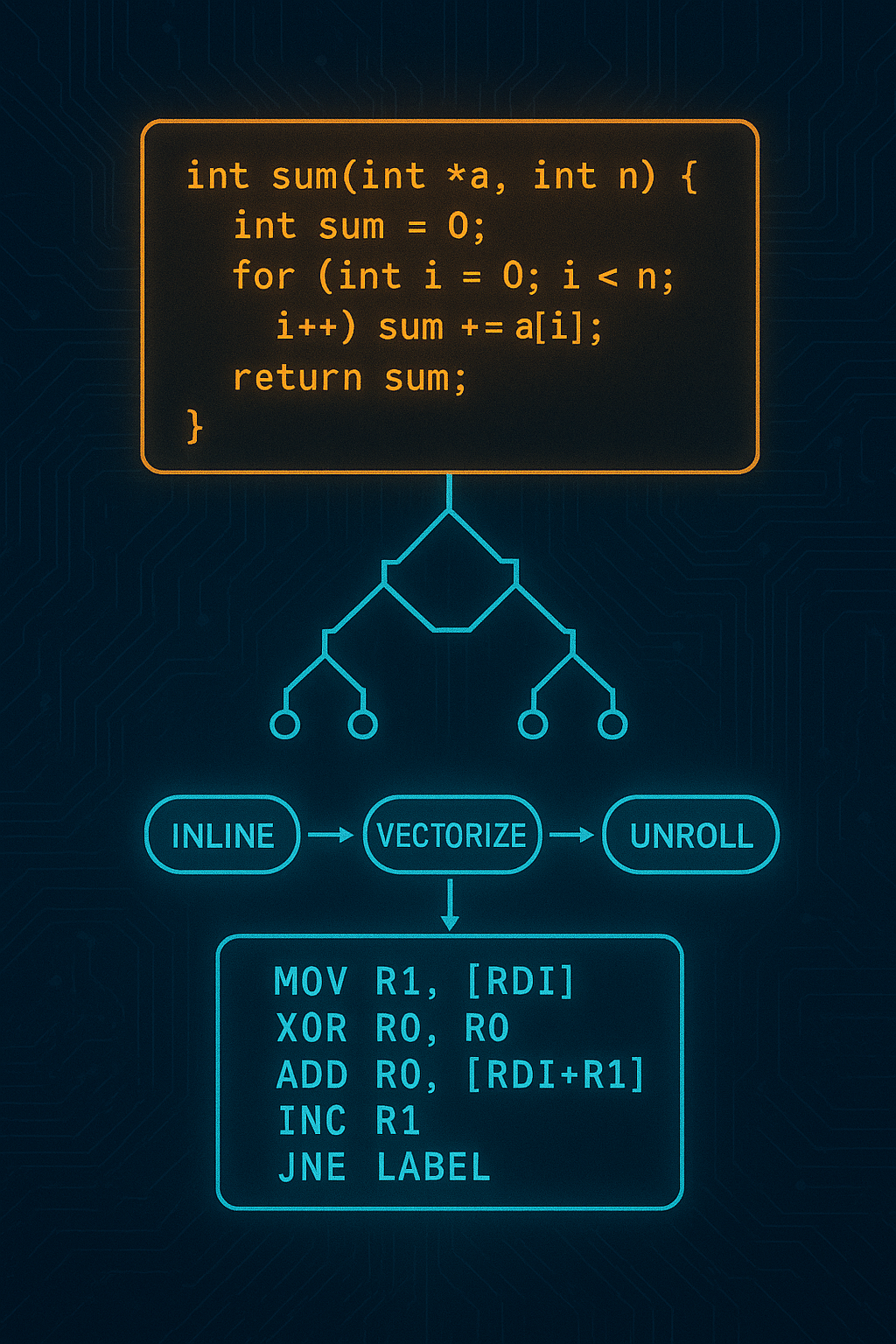

A deep dive into how modern compilers transform your code into efficient machine code. Explore optimization passes from constant folding to loop vectorization, and learn how to write code that compilers can optimize effectively.

When you compile your code with -O2 or -O3, something magical happens. The compiler applies dozens of optimization passes that can make your program run 10x faster—or more. Understanding these optimizations helps you write faster code and debug mysterious performance issues. Let’s explore how modern compilers transform source code into efficient machine code.

1. The Compilation Pipeline

Before diving into optimizations, let’s understand where they happen.

1.1 Compiler Phases

Source Code

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Front-end │ Parsing, type checking, AST generation

│ (Language- │ C, C++, Rust, Swift → IR

│ specific) │

└────────┬────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Middle-end │ ★ MOST OPTIMIZATIONS HAPPEN HERE ★

│ (IR-based │ Constant folding, inlining, loop opts

│ optimization) │ Dead code elimination, vectorization

└────────┬────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ Back-end │ Instruction selection, register allocation

│ (Target- │ Instruction scheduling, peephole opts

│ specific) │

└────────┬────────┘

│

▼

Machine Code

1.2 Intermediate Representation (IR)

LLVM IR is a popular intermediate representation:

; Source: int square(int x) { return x * x; }

define i32 @square(i32 %x) {

entry:

%result = mul i32 %x, %x

ret i32 %result

}

IR enables language-agnostic optimization: the same optimization passes work for C, C++, Rust, Swift, and other LLVM-based languages.

1.3 Optimization Levels

# GCC/Clang optimization levels

-O0 # No optimization (fast compile, slow code)

-O1 # Basic optimizations

-O2 # Most optimizations (production default)

-O3 # Aggressive (may increase code size)

-Os # Optimize for size

-Ofast # O3 + unsafe math optimizations

# View applied passes (Clang)

clang -O2 -mllvm -print-pipeline-passes file.c

2. Scalar Optimizations

The simplest optimizations work on individual values and expressions.

2.1 Constant Folding

Evaluate constant expressions at compile time:

// Before

int x = 2 + 3;

int y = 60 * 60 * 24;

// After constant folding

int x = 5;

int y = 86400;

This extends to function calls with constant arguments:

// Before

double pi_squared = pow(3.14159, 2);

// After (with -O2)

double pi_squared = 9.869587728099999;

2.2 Constant Propagation

Substitute known constant values:

// Before

int a = 5;

int b = a + 3;

int c = b * 2;

// After constant propagation

int a = 5;

int b = 8; // 5 + 3

int c = 16; // 8 * 2

2.3 Dead Code Elimination

Remove code that doesn’t affect output:

// Before

int compute(int x) {

int unused = x * x * x; // Never used

int result = x * 2;

return result;

}

// After DCE

int compute(int x) {

return x * 2;

}

2.4 Common Subexpression Elimination (CSE)

Compute repeated expressions once:

// Before

double distance = sqrt(x*x + y*y);

double normalized_x = x / sqrt(x*x + y*y);

double normalized_y = y / sqrt(x*x + y*y);

// After CSE

double temp = sqrt(x*x + y*y);

double distance = temp;

double normalized_x = x / temp;

double normalized_y = y / temp;

2.5 Strength Reduction

Replace expensive operations with cheaper equivalents:

// Before

int y = x * 2;

int z = x * 8;

int w = x / 4;

int v = x % 8;

// After strength reduction

int y = x << 1; // Shift instead of multiply

int z = x << 3; // Shift instead of multiply

int w = x >> 2; // Shift instead of divide (for positive x)

int v = x & 7; // AND instead of modulo (for power of 2)

2.6 Algebraic Simplification

Apply mathematical identities:

// Before

int a = x + 0;

int b = x * 1;

int c = x * 0;

int d = x - x;

int e = x | 0;

int f = x & x;

// After simplification

int a = x;

int b = x;

int c = 0;

int d = 0;

int e = x;

int f = x;

3. Control Flow Optimizations

Optimizations that restructure how code executes.

3.1 Inlining

Replace function calls with function body:

// Before

static inline int square(int x) { return x * x; }

int compute(int a, int b) {

return square(a) + square(b);

}

// After inlining

int compute(int a, int b) {

return a * a + b * b;

}

Inlining eliminates:

- Function call overhead

- Argument passing

- Return handling

- Enables further optimizations

// Inlining enables more optimization

int process(int x) {

if (x > 0) {

return abs(x); // abs() inlined

}

return 0;

}

// After inlining + simplification

int process(int x) {

if (x > 0) {

return x; // We know x > 0, so abs(x) = x

}

return 0;

}

3.2 Tail Call Optimization

Convert tail recursion to iteration:

// Before (recursive)

int factorial(int n, int acc) {

if (n <= 1) return acc;

return factorial(n - 1, n * acc); // Tail call

}

// After TCO (effectively)

int factorial(int n, int acc) {

while (n > 1) {

acc = n * acc;

n = n - 1;

}

return acc;

}

This prevents stack overflow and improves performance.

3.3 Branch Elimination

Remove branches with known outcomes:

// Before

void process(int *ptr) {

if (ptr == NULL) {

// Handle null

} else {

*ptr = 42;

}

if (ptr != NULL) { // Redundant check

printf("%d\n", *ptr);

}

}

// After branch elimination (in else branch context)

void process(int *ptr) {

if (ptr == NULL) {

// Handle null

} else {

*ptr = 42;

printf("%d\n", *ptr); // We know ptr != NULL

}

}

3.4 Loop-Invariant Code Motion

Move computations out of loops:

// Before

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = data[i] * (a + b) / c;

}

// After LICM

int temp = (a + b) / c; // Moved out of loop

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = data[i] * temp;

}

3.5 Jump Threading

Eliminate unnecessary jumps:

// Before

if (x > 0) {

flag = true;

}

if (flag) { // Redundant when x > 0

do_something();

}

// After jump threading (when x > 0)

if (x > 0) {

flag = true;

do_something(); // Directly threaded

}

if (flag && x <= 0) { // Only check when needed

do_something();

}

4. Loop Optimizations

Loops are where programs spend most of their time, so they receive special attention.

4.1 Loop Unrolling

Execute multiple iterations per loop:

// Before

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

sum += array[i];

}

// After unrolling (factor of 4)

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i += 4) {

sum += array[i];

sum += array[i + 1];

sum += array[i + 2];

sum += array[i + 3];

}

Benefits:

- Fewer branch instructions

- Better instruction-level parallelism

- Enables more CSE opportunities

4.2 Loop Fusion

Combine adjacent loops:

// Before

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] + 1;

}

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] * 2;

}

// After fusion

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] + 1;

c[i] = a[i] * 2; // Better cache locality

}

4.3 Loop Fission (Distribution)

Split a loop into multiple loops:

// Before (poor vectorization due to dependency)

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] + 1; // Can vectorize

c[i] = c[i-1] * 2; // Cannot vectorize (dependency)

}

// After fission

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] + 1; // Now vectorizable

}

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = c[i-1] * 2; // Sequential

}

4.4 Loop Interchange

Swap nested loop order for better memory access:

// Before (poor cache behavior - column-major access)

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Strided access

}

}

// After interchange (row-major access)

for (int i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Sequential access

}

}

4.5 Loop Vectorization

Use SIMD instructions to process multiple elements:

// Before

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

// After vectorization (conceptually)

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 8) { // Process 8 floats at once

__m256 va = _mm256_load_ps(&a[i]);

__m256 vb = _mm256_load_ps(&b[i]);

__m256 vc = _mm256_add_ps(va, vb);

_mm256_store_ps(&c[i], vc);

}

Modern compilers auto-vectorize when possible:

# Enable vectorization reports

clang -O2 -Rpass=loop-vectorize file.c

gcc -O2 -fopt-info-vec-optimized file.c

4.6 Loop Tiling (Blocking)

Improve cache utilization for nested loops:

// Before (matrix multiply - poor cache use)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

// After tiling (64x64 blocks fit in L1 cache)

#define TILE 64

for (int ii = 0; ii < N; ii += TILE) {

for (int jj = 0; jj < N; jj += TILE) {

for (int kk = 0; kk < N; kk += TILE) {

for (int i = ii; i < ii + TILE; i++) {

for (int j = jj; j < jj + TILE; j++) {

for (int k = kk; k < kk + TILE; k++) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

}

}

}

5. Memory Optimizations

Optimizations targeting memory access patterns.

5.1 Scalar Replacement of Aggregates (SROA)

Break structs into individual variables:

// Before

struct Point { int x, y; };

int distance_squared(struct Point p) {

return p.x * p.x + p.y * p.y;

}

// After SROA (at call site)

int distance_squared(int p_x, int p_y) {

return p_x * p_x + p_y * p_y;

}

This enables register allocation for struct members.

5.2 Memory to Register Promotion

Keep variables in registers instead of memory:

// Before (conceptual C, showing memory operations)

void compute(int *result) {

int temp; // On stack

temp = 5; // Store to memory

temp = temp + 3; // Load, add, store

*result = temp * 2; // Load, multiply, store

}

// After mem2reg

void compute(int *result) {

int temp = 5; // In register

temp = temp + 3; // Register operation

*result = temp * 2; // Single store

}

5.3 Load/Store Elimination

Remove redundant memory operations:

// Before

void update(int *ptr) {

*ptr = 10; // Store

int x = *ptr; // Load (redundant - we just stored 10)

*ptr = x + 1; // Store

}

// After elimination

void update(int *ptr) {

*ptr = 11; // Single store

}

5.4 Alias Analysis

Determine if pointers can refer to the same memory:

// Can these be optimized?

void compute(int *a, int *b, int *c) {

*a = *b + *c;

*a = *b + *c; // Redundant if a doesn't alias b or c

}

// With restrict keyword (C99)

void compute(int *restrict a, int *restrict b, int *restrict c) {

*a = *b + *c; // Compiler knows a, b, c don't overlap

// Second assignment definitely redundant

}

5.5 Prefetching

Insert prefetch instructions for predictable access:

// Compiler may insert prefetches for:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

// __builtin_prefetch(&data[i + 16]); // Implicit

sum += data[i];

}

6. Interprocedural Optimizations

Optimizations across function boundaries.

6.1 Link-Time Optimization (LTO)

Optimize across compilation units:

# Compile with LTO

clang -O2 -flto file1.c file2.c -o program

# Benefits:

# - Cross-file inlining

# - Whole-program dead code elimination

# - Better alias analysis

6.2 Interprocedural Constant Propagation

Propagate constants across functions:

// file1.c

int get_multiplier() { return 4; }

// file2.c

int scale(int x) {

return x * get_multiplier();

}

// After IPCP with LTO

int scale(int x) {

return x * 4; // Or: x << 2

}

6.3 Devirtualization

Replace virtual calls with direct calls:

// Before

class Base { virtual void foo() = 0; };

class Derived : public Base { void foo() override { /*...*/ } };

void call_foo(Base* b) {

b->foo(); // Virtual call through vtable

}

// After devirtualization (when type is known)

void call_foo(Derived* d) {

d->Derived::foo(); // Direct call

}

6.4 Function Cloning

Create specialized versions for specific call sites:

// Original

void process(int *data, int n, bool reverse) {

if (reverse) {

for (int i = n-1; i >= 0; i--) process_item(data[i]);

} else {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) process_item(data[i]);

}

}

// After cloning

void process_forward(int *data, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) process_item(data[i]);

}

void process_reverse(int *data, int n) {

for (int i = n-1; i >= 0; i--) process_item(data[i]);

}

// Call site uses appropriate clone based on known value

7. Target-Specific Optimizations

Optimizations that depend on the target architecture.

7.1 Instruction Selection

Choose optimal instructions for the target:

// Source

int count_ones(unsigned int x) {

int count = 0;

while (x) {

count += x & 1;

x >>= 1;

}

return count;

}

// On x86 with POPCNT support

int count_ones(unsigned int x) {

return __builtin_popcount(x); // Single instruction

}

7.2 Register Allocation

Assign variables to physical registers:

Virtual registers: Physical registers (x86-64):

v1 = load a rax = load a

v2 = load b rbx = load b

v3 = v1 + v2 rcx = rax + rbx

v4 = v3 * v1 rcx = rcx * rax

store v4 → result store rcx → result

Register pressure can force spills to memory, impacting performance.

7.3 Instruction Scheduling

Reorder instructions to hide latency:

; Before (stalls waiting for load)

mov rax, [ptr1] ; Load (latency: 4 cycles)

add rax, 1 ; Must wait for load

mov rbx, [ptr2] ; Load

add rbx, 2 ; Must wait for load

; After scheduling (overlap latencies)

mov rax, [ptr1] ; Start load 1

mov rbx, [ptr2] ; Start load 2 (parallel)

add rax, 1 ; Load 1 ready by now

add rbx, 2 ; Load 2 ready by now

7.4 SIMD Instruction Selection

Choose appropriate vector instructions:

// Compiler chooses based on target

float sum = a + b; // scalar: addss

// SSE: addps (4 floats)

// AVX: vaddps (8 floats)

// AVX-512: vaddps (16 floats)

# Target specific architectures

clang -march=skylake file.c # Use Skylake instructions

clang -march=native file.c # Use current CPU's features

clang -mavx2 -mfma file.c # Enable specific extensions

8. Profile-Guided Optimization (PGO)

Use runtime data to guide optimization decisions.

8.1 How PGO Works

# Step 1: Build instrumented binary

clang -O2 -fprofile-generate file.c -o program_instrumented

# Step 2: Run with representative workload

./program_instrumented < typical_input.txt

# Step 3: Build optimized binary using profile

clang -O2 -fprofile-use=default.profdata file.c -o program_optimized

8.2 PGO Benefits

// Without PGO: compiler guesses

if (rarely_true) { // Compiler assumes 50/50

cold_path();

} else {

hot_path();

}

// With PGO: compiler knows actual frequencies

if (rarely_true) { // Profile shows 0.1% taken

cold_path(); // Moved to separate cache line

} else {

hot_path(); // Inlined, optimized aggressively

}

PGO improves:

- Branch prediction hints

- Function inlining decisions

- Basic block layout

- Register allocation priorities

8.3 Feedback-Directed Optimization

Modern PGO uses sampling for low overhead:

# AutoFDO with Linux perf

perf record -b ./program # Sample branches

create_llvm_prof --binary=./program --profile=perf.data --out=program.afdo

clang -O2 -fprofile-sample-use=program.afdo file.c

9. Writing Optimizer-Friendly Code

Help the compiler help you.

9.1 Use const and restrict

// Help alias analysis

void add_arrays(

float *restrict result, // result doesn't alias others

const float *restrict a, // a is read-only

const float *restrict b, // b is read-only

int n

) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

// Enables vectorization without runtime alias checks

9.2 Prefer Local Variables

// Harder to optimize (could alias through ptr)

void bad(int *ptr) {

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

*ptr += i;

}

}

// Easier to optimize

void good(int *ptr) {

int sum = *ptr; // Load once

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

sum += i; // Register operation

}

*ptr = sum; // Store once

}

9.3 Avoid Pointer Aliasing

// May not vectorize (a and b might overlap)

void copy_bad(int *a, int *b, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] * 2;

}

}

// Will vectorize

void copy_good(int *restrict a, int *restrict b, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] * 2;

}

}

9.4 Use Appropriate Types

// size_t for array indexing

void sum(int *arr, size_t n) {

int sum = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) { // No sign extension needed

sum += arr[i];

}

}

// Appropriate width for data

void process(uint8_t *data, int n) { // 8-bit data

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

data[i] = data[i] >> 1;

}

}

9.5 Structure Data for Vectorization

// Array of Structures (AoS) - harder to vectorize

struct Particle { float x, y, z, mass; };

struct Particle particles[N];

// Structure of Arrays (SoA) - easier to vectorize

struct Particles {

float x[N], y[N], z[N], mass[N];

};

9.6 Mark Unlikely Branches

#define unlikely(x) __builtin_expect(!!(x), 0)

#define likely(x) __builtin_expect(!!(x), 1)

void process(int *data) {

if (unlikely(data == NULL)) {

handle_error();

return;

}

// Hot path continues here

}

10. Debugging Compiler Optimizations

When optimizations cause problems or you want to understand what’s happening.

10.1 Viewing Optimization Passes

# LLVM: print all optimization passes

clang -O2 -mllvm -debug-pass=Arguments file.c

# GCC: dump optimization info

gcc -O2 -fdump-tree-all -fdump-rtl-all file.c

# View generated assembly

clang -O2 -S -fverbose-asm file.c -o file.s

# Compare optimization levels

diff <(clang -O0 -S file.c -o -) <(clang -O2 -S file.c -o -)

10.2 Optimization Reports

# Clang optimization remarks

clang -O2 -Rpass=inline -Rpass-missed=inline file.c

clang -O2 -Rpass=loop-vectorize file.c

# GCC optimization info

gcc -O2 -fopt-info-vec-all file.c

gcc -O2 -fopt-info-inline-all file.c

10.3 Online Tools

Compiler Explorer (godbolt.org) is invaluable:

Features:

- Compare compilers and versions

- View assembly in real-time

- Diff different optimization levels

- See which source maps to which assembly

10.4 Preventing Optimization (for debugging)

// Prevent optimization of a variable

volatile int keep = result;

// Memory barrier (prevent reordering)

asm volatile("" ::: "memory");

// Prevent function inlining

__attribute__((noinline)) void debug_function() { ... }

// Prevent all optimizations for a function

__attribute__((optnone)) void debug_function() { ... } // Clang

__attribute__((optimize("O0"))) void debug_function() { ... } // GCC

11. Advanced Topics

11.1 Polyhedral Optimization

For complex loop nests, polyhedral compilation can find optimal transformations:

// Complex loop nest

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < M; j++)

for (int k = 0; k < K; k++)

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

// Polyhedral model represents as:

// { [i,j,k] : 0 <= i < N ∧ 0 <= j < M ∧ 0 <= k < K }

// Can automatically derive tiling, interchange, etc.

Tools like PLUTO and Polly (LLVM) use this approach.

11.2 Auto-Parallelization

Compilers can automatically parallelize some loops:

// With OpenMP

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

// Auto-parallelization (GCC)

// gcc -O2 -ftree-parallelize-loops=4 file.c

11.3 Sanitizer-Aware Optimization

Compilers adjust optimizations when sanitizers are enabled:

# AddressSanitizer reduces some optimizations

clang -O2 -fsanitize=address file.c

# UndefinedBehaviorSanitizer affects transformations

clang -O2 -fsanitize=undefined file.c

Some optimizations are disabled because they would mask bugs.

11.4 Whole-Program Optimization Challenges

Challenges:

- Compilation time scales with program size

- Memory usage can be extreme

- Incremental rebuilds are slow

- Debug info generation is complex

Mitigations:

- ThinLTO: scalable LTO with summary-based approach

- Distributed LTO: parallelize across machines

- Incremental LTO: cache and reuse work

12. The Evolution of Compiler Optimizations

12.1 Historical Perspective

1950s: First optimizing compilers (FORTRAN)

1970s: SSA form, dataflow analysis

1980s: Interprocedural optimization

1990s: Profile-guided optimization, SPEC benchmarks

2000s: JIT compilation, LLVM emergence

2010s: Auto-vectorization, polyhedral optimization

2020s: ML-guided optimization, domain-specific compilation

12.2 Modern Trends

Machine Learning for Compilation:

# ML can learn optimization heuristics

# Instead of hand-tuned rules:

if loop_size > 100 and estimated_benefit > threshold:

inline()

# Learn from data:

inline_probability = ml_model.predict(loop_features)

if inline_probability > 0.7:

inline()

Domain-Specific Compilers:

TensorFlow XLA: ML computation graphs → optimized GPU/TPU code

Halide: Image processing → optimized parallel code

MLIR: Multi-level IR for domain-specific optimization

12.3 Compiler Correctness

Optimizations must preserve semantics:

// This transformation is WRONG

// Before: x - 1 > y

// After: x > y + 1 (incorrect if y + 1 overflows!)

// Compilers use formal verification and extensive testing

// - Translation validation

- Random testing (Csmith)

// - Differential testing across compilers

13. Real-World Optimization Stories

13.1 The Famous Bounds Check Elimination

In a tight loop processing array elements, bounds checking can be expensive:

// Java-style array access with bounds checks

for (int i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

sum += array[i]; // Implicit bounds check every iteration

}

Modern JIT compilers (HotSpot, V8) recognize this pattern and eliminate redundant checks:

Analysis:

- Loop bounds: 0 to array.length

- Array index: i

- Since 0 <= i < array.length, bounds check always passes

- Hoist check outside loop or eliminate entirely

This optimization can provide 2-3x speedups in array-heavy code.

13.2 String Interning Gone Wrong

A production system exhibited puzzling performance characteristics:

// Original code

for (String s : data) {

if (s.equals("ACTIVE")) {

activeCount++;

}

}

After profiling, the team discovered the JIT compiler wasn’t optimizing equals() as expected. The solution was explicit string interning:

private static final String ACTIVE = "ACTIVE".intern();

for (String s : data) {

if (s == ACTIVE) { // Reference comparison after interning

activeCount++;

}

}

The lesson: understanding optimization limitations helps find workarounds.

13.3 Auto-Vectorization Failures

A team optimized image processing code expecting auto-vectorization:

void brighten(uint8_t *pixels, int n, int amount) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int val = pixels[i] + amount;

pixels[i] = val > 255 ? 255 : val; // Saturation

}

}

Checking compiler output revealed no vectorization. The issue was the saturation check creating control flow. The fix used intrinsics:

void brighten(uint8_t *pixels, int n, int amount) {

__m128i vamount = _mm_set1_epi16(amount);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 16) {

__m128i vpix = _mm_loadu_si128((__m128i*)&pixels[i]);

// ... SIMD saturation arithmetic

}

}

13.4 The Inlining Cliff

A performance regression appeared after a “minor” code change:

// Before: 15 lines, always inlined

int fastPath(Data& d) {

// Simple computation

return d.x + d.y * d.z;

}

// After: 52 lines, not inlined

int fastPath(Data& d) {

// Added validation, logging

if (!d.valid) { log("invalid"); return -1; }

// ... more code ...

return d.x + d.y * d.z;

}

The function exceeded the inlining threshold, causing a 3x slowdown in the hot loop that called it. Solution: split into fast path (inlined) and slow path (not inlined).

inline int fastPath(Data& d) {

if (__builtin_expect(!d.valid, 0)) {

return slowPath(d); // Outlined error handling

}

return d.x + d.y * d.z;

}

13.5 LTO Unlocks Cross-Module Inlining

A microservices framework showed surprising speedups with LTO:

Before LTO:

- Each module compiled separately

- Interface calls go through function pointers

- Virtual dispatch for polymorphism

- 15% CPU in call overhead

After LTO:

- Whole-program visibility

- Devirtualization of common patterns

- Cross-module inlining

- Call overhead reduced to 2%

Result: 18% overall performance improvement

The key insight: modular code design doesn’t mean modular compilation.

14. Compiler Optimization Pitfalls

14.1 Undefined Behavior Exploitation

Compilers exploit undefined behavior aggressively:

int foo(int x) {

if (x + 1 > x) {

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

// Optimized to (assuming signed overflow is UB):

int foo(int x) {

return 1; // Always true if no overflow

}

This can remove security checks:

void vulnerable(char *buf, int len) {

if (len > MAX_LEN) return; // Bounds check

if (len < 0) return; // Negativity check

// len + HEADER_SIZE might overflow!

char *p = malloc(len + HEADER_SIZE);

// Compiler might optimize assuming no overflow

}

14.2 Floating-Point Optimization Dangers

// -ffast-math can change results

float sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

sum += data[i];

}

// With -ffast-math, compiler might reorder:

// (a + b) + c != a + (b + c) in floating point!

// This can cause reproducibility issues

Guidelines for floating-point:

- Use

-ffast-mathonly when precision isn’t critical - Consider

-ffp-contract=fastfor FMA without full fast-math - Test numerical stability after enabling optimizations

14.3 Memory Model Violations

Optimizers assume single-threaded execution unless told otherwise:

// Broken without synchronization

int flag = 0;

int data = 0;

void producer() {

data = 42; // Might be reordered after flag

flag = 1;

}

void consumer() {

while (flag == 0); // Might be optimized to if (flag == 0) while(1);

use(data);

}

The fix requires proper atomics or volatile:

#include <stdatomic.h>

atomic_int flag = 0;

int data = 0;

void producer() {

data = 42;

atomic_store_explicit(&flag, 1, memory_order_release);

}

void consumer() {

while (atomic_load_explicit(&flag, memory_order_acquire) == 0);

use(data);

}

14.4 Debug vs Release Differences

Code that works in debug can break in release:

// Uninitialized in release, zero in debug

int compute() {

int result; // Uninitialized

// Forgot assignment on some path

return result; // UB in release, often 0 in debug

}

// Order-of-evaluation issues

map[key] = process(map[key]);

// Debug: predictable order

// Release: order undefined, map might rehash

14.5 The Observer Effect

Measuring performance can change it:

void hot_function() {

// Very tight loop

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

result += data[i];

}

}

// Adding timing code:

void hot_function() {

auto start = now(); // Prevents some optimizations

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

result += data[i];

}

auto end = now();

log(end - start); // Side effect changes optimization

}

Solutions include:

- Use sampling profilers (perf, VTune)

- Profile release builds

- Minimize instrumentation

15. The Future of Compiler Optimization

15.1 Machine Learning Integration

Modern compilers are beginning to incorporate ML:

Traditional approach:

- Hand-tuned heuristics

- if (loop_count > 100 && benefit > cost) inline()

- Requires expert knowledge, often suboptimal

ML approach:

- Learn from millions of programs

- Predict optimal decisions

- Adapt to new architectures automatically

Research examples:

- Google's ML inlining for LLVM

- Microsoft's learning-based register allocation

- Intel's ML-guided code generation

15.2 Domain-Specific Compilation

Specialized compilers for specific domains:

# TensorFlow XLA compiles computation graphs

@tf.function(jit_compile=True)

def model(x):

return tf.matmul(x, w) + b

# XLA optimizations:

# - Fuse operations (matmul + add → single kernel)

# - Optimize memory layout for hardware

# - Generate code for GPU/TPU

Similar patterns exist for:

- Image processing (Halide)

- Database queries (query compilers)

- Cryptography (specialized constant-time compilation)

15.3 Hardware-Software Co-Design

As hardware becomes more specialized, compilers adapt:

Modern challenges:

- Heterogeneous systems (CPU + GPU + TPU + FPGA)

- Memory hierarchies (L1/L2/L3/HBM/DRAM/SSD)

- Power constraints (frequency scaling, dark silicon)

Compiler responses:

- Unified IR across accelerators (MLIR)

- Automatic data placement and movement

- Power-aware optimization passes

15.4 Security-Focused Compilation

Compilers increasingly target security:

// Stack canaries

void vulnerable() {

char buffer[64];

// Compiler inserts: canary = random_value

gets(buffer);

// Compiler inserts: if (canary != expected) abort()

}

// Control-Flow Integrity

void call_function(void (*fptr)()) {

// Compiler inserts: verify fptr in allowed targets

fptr();

}

Emerging techniques:

- Pointer authentication (ARM PA)

- Shadow stacks

- Memory tagging (MTE)

15.5 Verified Compilation

Ensuring optimizations preserve correctness:

CompCert: Formally verified C compiler

- Mathematical proof of correctness

- Guarantees: compiled code behaves like source

- Used in safety-critical domains (aviation, medical)

Challenges:

- Verification effort is substantial

- Performance gap with production compilers

- Limited optimization scope

Future: combining formal methods with aggressive optimization

16. Summary

Modern compilers apply sophisticated transformations to make code fast:

Scalar optimizations:

- Constant folding and propagation

- Dead code elimination

- Common subexpression elimination

- Strength reduction

Control flow optimizations:

- Function inlining

- Branch elimination

- Tail call optimization

Loop optimizations:

- Unrolling and vectorization

- Fusion, fission, and interchange

- Loop-invariant code motion

- Tiling for cache

Memory optimizations:

- Register promotion

- Load/store elimination

- Alias analysis

Interprocedural optimizations:

- Link-time optimization

- Devirtualization

- Cross-module inlining

Target-specific optimizations:

- Instruction selection

- Register allocation

- SIMD vectorization

Key takeaways:

- Trust the compiler: Modern compilers are remarkably good

- Write clear code: Let the compiler optimize; focus on readability

- Help when needed: Use restrict, const, and hints judiciously

- Profile first: Don’t optimize blindly; measure

- Understand limits: Some optimizations need source-level changes

Understanding compiler optimizations makes you a better programmer. You’ll write code that compilers can optimize effectively, diagnose performance issues more quickly, and appreciate the incredible engineering in modern compilation systems.