CPU Caches and Cache Coherence: The Memory Hierarchy That Makes Modern Computing Fast

A comprehensive exploration of how CPU caches bridge the processor-memory speed gap. Learn about cache architecture, replacement policies, coherence protocols, and how to write cache-friendly code for maximum performance.

Modern CPUs can execute billions of instructions per second, but main memory takes hundreds of cycles to respond. Without caches, processors would spend most of their time waiting for data. The cache hierarchy is one of the most important innovations in computer architecture, and understanding it is essential for writing high-performance software.

1. The Memory Wall Problem

The fundamental challenge that caches solve.

1.1 The Speed Gap

Component Access Time Relative Speed

─────────────────────────────────────────────────

CPU Register ~0.3 ns 1x (baseline)

L1 Cache ~1 ns ~3x slower

L2 Cache ~3-4 ns ~10x slower

L3 Cache ~10-20 ns ~30-60x slower

Main Memory ~50-100 ns ~150-300x slower

NVMe SSD ~20,000 ns ~60,000x slower

HDD ~10,000,000 ns ~30,000,000x slower

1.2 Why the Gap Exists

Memory technology tradeoffs:

SRAM (caches):

├─ Fast: 6 transistors per bit

├─ Expensive: ~100x cost per bit vs DRAM

├─ Power hungry

└─ Low density

DRAM (main memory):

├─ Slow: 1 transistor + 1 capacitor per bit

├─ Cheap: high density

├─ Needs refresh (capacitors leak)

└─ Better power per bit

1.3 The Solution: Caching

Caches exploit two key principles:

Temporal Locality:

"If you accessed it recently, you'll probably access it again"

Example: Loop counter variable

Spatial Locality:

"If you accessed this address, you'll probably access nearby addresses"

Example: Sequential array traversal

2. Cache Architecture Fundamentals

How caches are organized internally.

2.1 Cache Lines

Caches don’t store individual bytes—they store fixed-size blocks:

Typical cache line: 64 bytes

Memory address: 0x1234_5678

└──────┴──┘

Tag │

└─ Offset within cache line (6 bits for 64B)

When you read one byte, the entire 64-byte line is loaded:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Cache Line (64 bytes) │

│ [byte0][byte1][byte2]...[byte63] │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

2.2 Cache Organization Types

1. Direct-Mapped Cache:

Each memory address maps to exactly one cache location

Pros: Simple, fast lookup

Cons: Conflict misses (two addresses compete for same slot)

Memory Address → Hash → Single Cache Location

2. Fully Associative Cache:

Any memory address can go in any cache location

Pros: No conflict misses

Cons: Expensive to search all entries

Memory Address → Search All → Any Cache Location

3. Set-Associative Cache (most common):

Address maps to a set; can go in any slot within that set

4-way set associative: 4 slots per set

8-way set associative: 8 slots per set

Memory Address → Hash → Set → One of N Slots

2.3 Anatomy of a Cache Entry

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Cache Entry │

├──────┬───────┬───────┬─────────────────────────────────────────┤

│Valid │ Dirty │ Tag │ Data (Cache Line) │

│ (1b) │ (1b) │(~30b) │ (64 bytes) │

├──────┼───────┼───────┼─────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 1 │ 0 │ 0x1A3 │ [64 bytes of data from memory] │

└──────┴───────┴───────┴─────────────────────────────────────────┘

Valid: Is this entry holding real data?

Dirty: Has this data been modified (needs writeback)?

Tag: High bits of address for matching

Data: The actual cached bytes

2.4 Address Breakdown

For a 32KB, 8-way set associative cache with 64-byte lines:

Total entries: 32KB / 64B = 512 entries

Sets: 512 / 8 = 64 sets

Bits needed for set index: log2(64) = 6 bits

Address breakdown (for 48-bit virtual address):

┌────────────────────────┬────────┬────────┐

│ Tag │ Set │ Offset │

│ (36 bits) │(6 bits)│(6 bits)│

└────────────────────────┴────────┴────────┘

Offset: Which byte within the 64-byte line

Set: Which set to look in

Tag: For matching within the set

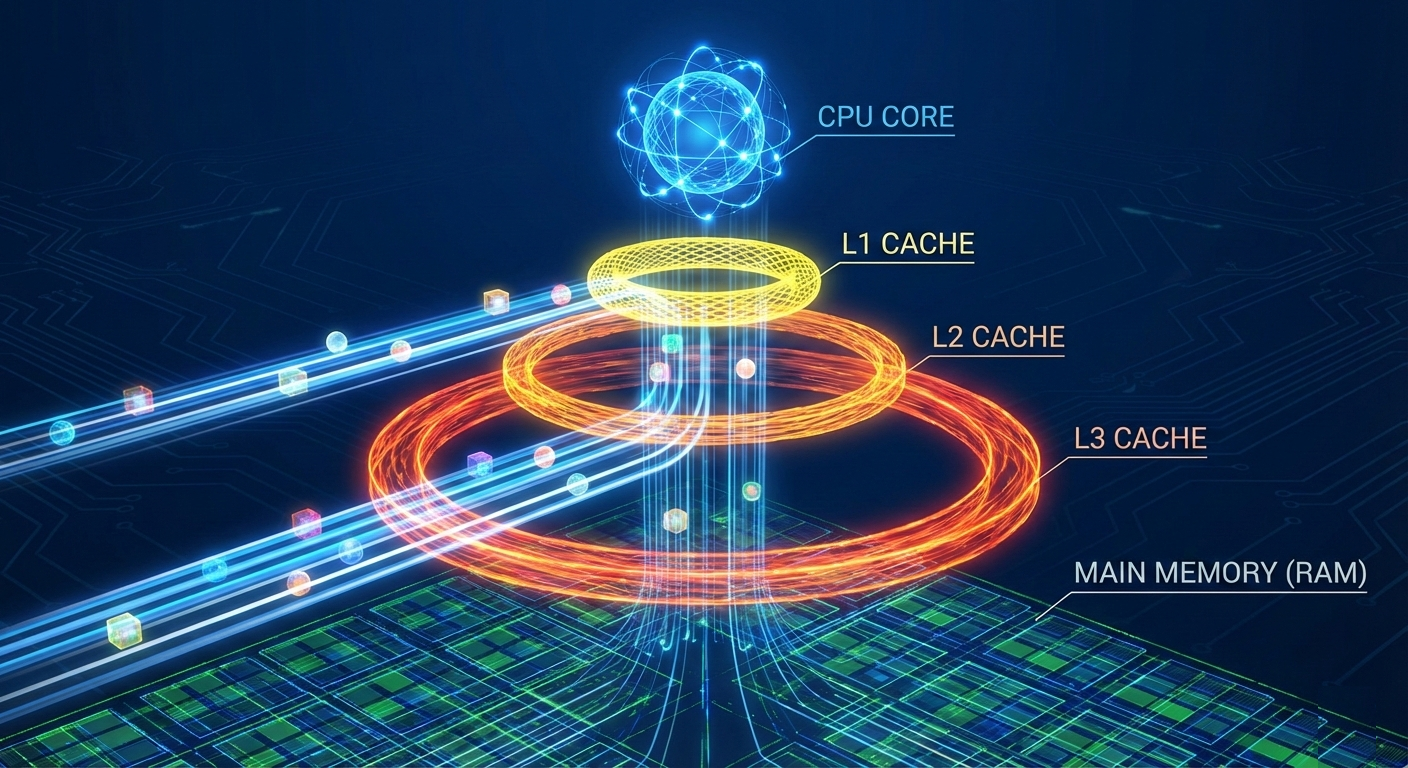

3. The Cache Hierarchy

Modern CPUs have multiple cache levels.

3.1 Typical Modern Configuration

┌─────────────┐

│ CPU Core │

└──────┬──────┘

│

┌──────▼──────┐

│ L1 I-Cache │ 32-64 KB, ~4 cycles

│ L1 D-Cache │ 32-64 KB, ~4 cycles

└──────┬──────┘

│

┌──────▼──────┐

│ L2 Cache │ 256-512 KB, ~12 cycles

└──────┬──────┘

│

┌────────────▼────────────┐

│ L3 Cache │ 8-64 MB, ~40 cycles

│ (Shared across cores)│

└────────────┬────────────┘

│

┌────────────▼────────────┐

│ Main Memory │ ~200 cycles

└─────────────────────────┘

3.2 Inclusive vs Exclusive Hierarchies

Inclusive (Intel):

- L3 contains copy of everything in L1/L2

- Simpler coherence

- Wastes some capacity

L1: [A, B, C]

L2: [A, B, C, D, E]

L3: [A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H]

Exclusive (AMD):

- Each level holds unique data

- Better capacity utilization

- More complex coherence

L1: [A, B]

L2: [C, D, E]

L3: [F, G, H, I, J]

Non-Inclusive Non-Exclusive (NINE):

- L3 doesn't guarantee inclusion

- Flexible eviction policies

- Modern Intel uses this

3.3 Private vs Shared Caches

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ Core 0 │ │ Core 1 │ │ Core 2 │ │ Core 3 │

├─────────┤ ├─────────┤ ├─────────┤ ├─────────┤

│L1 (Priv)│ │L1 (Priv)│ │L1 (Priv)│ │L1 (Priv)│

├─────────┤ ├─────────┤ ├─────────┤ ├─────────┤

│L2 (Priv)│ │L2 (Priv)│ │L2 (Priv)│ │L2 (Priv)│

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │ │ │

└───────────┴─────┬─────┴───────────┘

│

┌────────▼────────┐

│ L3 (Shared) │

└─────────────────┘

Private caches: Low latency, no sharing overhead

Shared caches: Better utilization, requires coherence

4. Cache Replacement Policies

When the cache is full, which line gets evicted?

4.1 Common Policies

LRU (Least Recently Used):

- Evict the line accessed longest ago

- Optimal for many workloads

- Expensive to implement exactly

Pseudo-LRU:

- Approximates LRU with less hardware

- Tree-based tracking

- Good enough in practice

Random:

- Surprisingly effective

- Simple to implement

- Avoids pathological patterns

RRIP (Re-Reference Interval Prediction):

- Intel's modern approach

- Predicts reuse distance

- Handles scan-resistant workloads

4.2 LRU Implementation

True LRU for 4-way associative:

- Need to track order of 4 elements

- 4! = 24 states = 5 bits per set

- Update on every access

Tree-PLRU (Pseudo-LRU):

[0] Root bit

/ \

[1] [2] Level 1 bits

/ \ / \

W0 W1 W2 W3 Cache ways

On access to W1: Set root→left, level1-left→right

On eviction: Follow bits to find victim

Only 3 bits per set (vs 5 for true LRU)

4.3 Replacement Policy Impact

// Different access patterns favor different policies

// Sequential scan (LRU performs poorly):

for (int i = 0; i < HUGE_ARRAY; i++) {

sum += array[i]; // Each line used once, evicted before reuse

}

// Working set that fits in cache (LRU works well):

for (int iter = 0; iter < 1000; iter++) {

for (int i = 0; i < CACHE_SIZE; i++) {

sum += array[i]; // Lines stay in cache

}

}

// Random access (all policies similar):

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

sum += array[random_indices[i]];

}

5. Cache Coherence

When multiple cores have caches, how do we keep them consistent?

5.1 The Coherence Problem

Initial state: memory[X] = 0

Core 0 L1: [X = 0] Core 1 L1: [X = 0]

Core 0 writes X = 1:

Core 0 L1: [X = 1] Core 1 L1: [X = 0] ← STALE!

Without coherence:

- Core 1 reads stale data

- Program behaves incorrectly

- Multithreaded code breaks

5.2 MESI Protocol

The most common cache coherence protocol:

States:

┌───────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ State │ Meaning │

├───────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Modified (M) │ Only copy, dirty (different from memory) │

│ Exclusive (E) │ Only copy, clean (matches memory) │

│ Shared (S) │ Multiple copies may exist, clean │

│ Invalid (I) │ Not valid, must fetch from elsewhere │

└───────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────┘

5.3 MESI State Transitions

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

▼ │

┌───────────┐ Read hit ┌───────────┐ │

│ │◄────────────►│ │ │

│ Invalid │ │ Shared │─────────┤

│ (I) │ │ (S) │ Write │

└─────┬─────┘ └─────┬─────┘ (upgrade)

│ │ │

│ Read miss │ Other core │

│ (no other copy) │ writes │

▼ ▼ │

┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐ │

│ Exclusive │──────────────│ Modified │◄────────┘

│ (E) │ Write │ (M) │

└───────────┘ └───────────┘

5.4 Coherence Operations

Scenario: Core 0 has line in M state, Core 1 wants to read

1. Core 1 issues read request on bus

2. Core 0 snoops the bus, sees request for its line

3. Core 0 provides data (cache-to-cache transfer)

4. Core 0 transitions M → S

5. Core 1 receives data in S state

6. Memory may or may not be updated (depends on protocol variant)

This is called a "snoop" or "intervention"

5.5 MOESI and MESIF Extensions

MOESI (AMD):

- Adds Owned (O) state

- Owner provides data, memory not updated

- Reduces memory traffic

MESIF (Intel):

- Adds Forward (F) state

- One cache designated to respond

- Reduces duplicate responses

Example with Owned state:

Core 0: Modified [X = 5]

Core 1: Read request

Result: Core 0 → Owned, Core 1 → Shared

Memory still has old value (only owner has current)

6. False Sharing

A critical performance pitfall in multithreaded code.

6.1 The Problem

// Looks innocent...

struct Counters {

long counter0; // 8 bytes

long counter1; // 8 bytes

};

struct Counters counters;

// Thread 0:

void thread0() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

counters.counter0++; // Only touches counter0

}

}

// Thread 1:

void thread1() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

counters.counter1++; // Only touches counter1

}

}

// But both counters are in the SAME cache line!

// Every write invalidates the other core's cache

// Result: 10-100x slower than expected

6.2 Visualizing False Sharing

Cache line (64 bytes):

┌────────────────┬────────────────┬─────────────────────────────┐

│ counter0 │ counter1 │ (padding) │

│ (8 bytes) │ (8 bytes) │ (48 bytes) │

└────────────────┴────────────────┴─────────────────────────────┘

▲ ▲

│ │

Thread 0 Thread 1

writes writes

Every write:

1. Writer invalidates other core's cache line

2. Other core must fetch updated line

3. Then it writes and invalidates the first core

4. Ping-pong of cache line between cores

6.3 The Solution: Padding

#define CACHE_LINE_SIZE 64

struct Counters {

alignas(CACHE_LINE_SIZE) long counter0;

alignas(CACHE_LINE_SIZE) long counter1;

};

// Or with explicit padding:

struct Counters {

long counter0;

char padding0[CACHE_LINE_SIZE - sizeof(long)];

long counter1;

char padding1[CACHE_LINE_SIZE - sizeof(long)];

};

// C++17 hardware_destructive_interference_size:

#include <new>

struct Counters {

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) long counter0;

alignas(std::hardware_destructive_interference_size) long counter1;

};

6.4 Measuring False Sharing

# Linux perf can detect cache line contention

perf c2c record ./program

perf c2c report

# Output shows:

# - Cachelines with high contention

# - Which loads/stores conflict

# - HITM (Hit Modified) events

7. Writing Cache-Friendly Code

Practical techniques for better cache utilization.

7.1 Sequential Access Patterns

// Good: Sequential access (spatial locality)

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

sum += array[i]; // Next element likely in same cache line

}

// Bad: Strided access

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += 16) {

sum += array[i]; // Only use 1/16 of each cache line

}

// Terrible: Random access

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

sum += array[rand() % N]; // No locality

}

7.2 Loop Ordering for Multi-Dimensional Arrays

#define ROWS 1000

#define COLS 1000

int matrix[ROWS][COLS]; // Row-major in C

// Good: Row-major traversal (matches memory layout)

for (int i = 0; i < ROWS; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < COLS; j++) {

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Sequential in memory

}

}

// Bad: Column-major traversal (cache thrashing)

for (int j = 0; j < COLS; j++) {

for (int i = 0; i < ROWS; i++) {

sum += matrix[i][j]; // Stride of COLS * sizeof(int)

}

}

// Performance difference: often 10-50x!

7.3 Structure Layout Optimization

// Bad: Poor cache utilization

struct Bad {

char a; // 1 byte + 7 padding

double b; // 8 bytes

char c; // 1 byte + 7 padding

double d; // 8 bytes

}; // Total: 32 bytes, only 18 used

// Good: Grouped by size

struct Good {

double b; // 8 bytes

double d; // 8 bytes

char a; // 1 byte

char c; // 1 byte + 6 padding

}; // Total: 24 bytes, 18 used

// Best for hot/cold: Separate structures

struct Hot {

double b;

double d;

};

struct Cold {

char a;

char c;

};

7.4 Data-Oriented Design

// Object-Oriented (cache-unfriendly for bulk operations):

struct Entity {

float x, y, z; // Position

float vx, vy, vz; // Velocity

float health;

char name[32];

int id;

// ... more fields

};

Entity entities[10000];

// Update positions: loads entire struct, uses only 24 bytes

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

entities[i].x += entities[i].vx;

entities[i].y += entities[i].vy;

entities[i].z += entities[i].vz;

}

// Data-Oriented (cache-friendly):

struct Positions { float x[10000], y[10000], z[10000]; };

struct Velocities { float vx[10000], vy[10000], vz[10000]; };

Positions pos;

Velocities vel;

// Update positions: sequential access, full cache line utilization

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

pos.x[i] += vel.vx[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

pos.y[i] += vel.vy[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

pos.z[i] += vel.vz[i];

}

7.5 Blocking (Loop Tiling)

// Matrix multiply without blocking

// Each pass through B column thrashes cache

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

// Matrix multiply with blocking

// Process cache-sized blocks

#define BLOCK 64 // Fits in L1 cache

for (int ii = 0; ii < N; ii += BLOCK) {

for (int jj = 0; jj < N; jj += BLOCK) {

for (int kk = 0; kk < N; kk += BLOCK) {

// Mini matrix multiply on cached blocks

for (int i = ii; i < min(ii+BLOCK, N); i++) {

for (int j = jj; j < min(jj+BLOCK, N); j++) {

for (int k = kk; k < min(kk+BLOCK, N); k++) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

}

}

}

8. Cache Prefetching

Bringing data into cache before it’s needed.

8.1 Hardware Prefetching

Modern CPUs detect patterns and prefetch automatically:

Patterns detected:

- Sequential: array[0], array[1], array[2]...

- Strided: array[0], array[4], array[8]...

- Some complex patterns on modern CPUs

Hardware prefetcher limitations:

- Can't cross page boundaries (4KB)

- Limited number of streams tracked

- Irregular patterns not detected

8.2 Software Prefetching

#include <xmmintrin.h> // For _mm_prefetch

void process_array(int *data, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

// Prefetch data for future iterations

_mm_prefetch(&data[i + 16], _MM_HINT_T0); // L1 cache

// Process current element

process(data[i]);

}

}

// Prefetch hints:

// _MM_HINT_T0: Prefetch to L1 (and all levels)

// _MM_HINT_T1: Prefetch to L2 (and L3)

// _MM_HINT_T2: Prefetch to L3 only

// _MM_HINT_NTA: Non-temporal (don't pollute cache)

8.3 When Prefetching Helps

// Prefetching helps: Predictable but non-sequential access

void linked_list_traverse(Node *head) {

Node *current = head;

while (current) {

// Prefetch next node while processing current

if (current->next) {

_mm_prefetch(current->next, _MM_HINT_T0);

}

process(current);

current = current->next;

}

}

// Prefetching hurts: Already sequential (hardware handles it)

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

_mm_prefetch(&array[i+16], _MM_HINT_T0); // Wasteful

sum += array[i]; // Hardware prefetcher already doing this

}

9. Cache Performance Metrics

Measuring and understanding cache behavior.

9.1 Key Metrics

Hit Rate = Hits / (Hits + Misses)

Miss Rate = 1 - Hit Rate

MPKI = Misses Per Kilo Instructions

Types of misses (the "3 Cs"):

- Compulsory: First access to a line (cold miss)

- Capacity: Working set exceeds cache size

- Conflict: Multiple addresses map to same set

9.2 Using Performance Counters

# Linux perf for cache statistics

perf stat -e L1-dcache-loads,L1-dcache-load-misses,\

LLC-loads,LLC-load-misses ./program

# Example output:

# 1,234,567,890 L1-dcache-loads

# 12,345,678 L1-dcache-load-misses # 1% miss rate

# 12,345,000 LLC-loads

# 123,456 LLC-load-misses # 1% of L1 misses hit memory

9.3 Cache Miss Visualization

# Cachegrind for detailed cache simulation

valgrind --tool=cachegrind ./program

cg_annotate cachegrind.out.*

# Output shows per-line cache behavior:

# Ir I1mr ILmr Dr D1mr DLmr Dw D1mw DLmw

# 1000000 0 0 1000000 250000 0 0 0 0

# for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 64) sum += array[i];

# Dr: Data reads

# D1mr: L1 data read misses

# DLmr: Last-level cache read misses

9.4 Working Set Analysis

// Determine effective working set size

// by measuring performance vs array size

#include <time.h>

void measure_cache_sizes() {

for (int size = 1024; size <= 64*1024*1024; size *= 2) {

char *array = malloc(size);

clock_t start = clock();

// Random accesses within array

for (int i = 0; i < 10000000; i++) {

array[rand() % size]++;

}

clock_t end = clock();

double time = (double)(end - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

printf("Size: %8d KB, Time: %.3f s\n", size/1024, time);

free(array);

}

}

// Output shows jumps at cache boundaries:

// Size: 1 KB, Time: 0.150 s ← Fits in L1

// Size: 2 KB, Time: 0.151 s

// ...

// Size: 32 KB, Time: 0.155 s ← L1 boundary

// Size: 64 KB, Time: 0.280 s ← Falls out of L1

// ...

// Size: 256 KB, Time: 0.290 s ← L2 boundary

// Size: 512 KB, Time: 0.850 s ← Falls out of L2

10. Advanced Cache Topics

10.1 Non-Temporal Stores

Bypass cache for write-once data:

#include <emmintrin.h>

void write_without_caching(float *dest, float *src, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 4) {

__m128 data = _mm_load_ps(&src[i]);

_mm_stream_ps(&dest[i], data); // Bypass cache

}

_mm_sfence(); // Ensure stores complete

}

// Use when:

// - Writing large amounts of data

// - Data won't be read again soon

// - Don't want to pollute cache

10.2 Cache Partitioning (Intel CAT)

# Intel Cache Allocation Technology

# Partition L3 cache between applications

# Check support

cat /sys/fs/resctrl/info/L3/cbm_mask

# Create partition with 4 cache ways

mkdir /sys/fs/resctrl/partition1

echo "0xf" > /sys/fs/resctrl/partition1/schemata

# Assign process to partition

echo $PID > /sys/fs/resctrl/partition1/tasks

Use cases:

- Isolate noisy neighbors

- Guarantee cache for latency-sensitive tasks

- Prevent cache thrashing between workloads

10.3 NUMA and Cache Considerations

NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access):

┌────────────────────┐ ┌────────────────────┐

│ Socket 0 │ │ Socket 1 │

│ ┌──────────────┐ │ │ ┌──────────────┐ │

│ │ Cores │ │ │ │ Cores │ │

│ └──────┬───────┘ │ │ └──────┬───────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ ┌──────▼───────┐ │ │ ┌──────▼───────┐ │

│ │ L3 Cache │ │ │ │ L3 Cache │ │

│ └──────┬───────┘ │ │ └──────┬───────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ ┌──────▼───────┐ │ │ ┌──────▼───────┐ │

│ │Local Memory │◄─┼────┼─►│Local Memory │ │

│ └──────────────┘ │ │ └──────────────┘ │

└────────────────────┘ └────────────────────┘

│ │

└────────┬────────────────┘

│

Interconnect

Local memory access: ~100 ns

Remote memory access: ~150-200 ns

Cache coherence across sockets: expensive!

10.4 Persistent Memory and Caching

// Intel Optane DC Persistent Memory

// New caching considerations

#include <libpmem.h>

void persist_data(void *dest, void *src, size_t len) {

memcpy(dest, src, len);

// Ensure data reaches persistent memory

// (not just CPU cache)

pmem_persist(dest, len);

}

// Cache line flush instructions:

// CLFLUSH: Flush and invalidate

// CLFLUSHOPT: Optimized flush (can be parallel)

// CLWB: Write back without invalidate (preferred)

11. Historical Evolution

11.1 Cache History

1960s: First cache (IBM System/360 Model 85)

- 16-32 KB

- Proved caching concept

1980s: On-chip L1 caches

- Intel 486: 8 KB unified cache

- Brought cache onto CPU die

1990s: Split I/D caches, L2 on package

- Pentium: separate I-cache and D-cache

- Pentium Pro: L2 on same package

2000s: L2 on-die, L3 introduced

- Pentium 4: on-die L2

- Core 2: shared L3

2010s: Large shared L3, advanced coherence

- Sandy Bridge: 8-way L3

- AMD Zen: L3 victim cache

2020s: 3D V-cache, larger L3

- AMD 3D V-Cache: 96 MB L3

- Intel Hybrid: different caches for P/E cores

11.2 Future Directions

Emerging trends:

- 3D-stacked cache (more capacity)

- Adaptive replacement policies

- ML-based prefetching

- Near-memory processing

- Processing-in-cache architectures

Challenges:

- Power scaling limits cache growth

- Coherence overhead increases with core count

- Memory wall continues to widen

12. Real-World Cache Optimization Case Studies

12.1 Database Buffer Pools

Database systems carefully manage cache utilization:

PostgreSQL buffer pool strategy:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Shared Buffer Pool │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Ring Buffers (for sequential scans) │

│ ├─ Limited size (256KB default) │

│ └─ Prevents cache pollution from full scans │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Clock Sweep (for random access) │

│ ├─ Usage count per page │

│ └─ Popular pages stay resident │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The lesson: Application-level caching must consider

CPU cache effects too. Page layout affects L1/L2 hit rates.

12.2 High-Frequency Trading

Financial systems obsess over cache behavior:

// HFT order book: hot data must fit in L1

struct alignas(64) Order { // Cache line aligned

uint64_t price;

uint64_t quantity;

uint64_t order_id;

uint32_t side;

uint32_t flags;

// Exactly 32 bytes - two orders per cache line

};

// Top of book (most accessed) kept separate

struct alignas(64) TopOfBook {

uint64_t best_bid;

uint64_t best_ask;

uint64_t bid_size;

uint64_t ask_size;

// Fits in single cache line

};

// Result: Critical path accesses 1-2 cache lines

// Latency: sub-microsecond order processing

12.3 Game Engine Entity Systems

Modern game engines use data-oriented design:

// Traditional OOP (cache-unfriendly):

class Entity {

Transform transform; // 64 bytes

Physics physics; // 128 bytes

Renderer renderer; // 256 bytes

AI ai; // 512 bytes

// ... many more components

};

vector<Entity> entities; // Huge stride

// Update physics: loads entire Entity for each

for (auto& e : entities) {

e.physics.update(); // Cache miss likely

}

// Data-oriented (cache-friendly):

struct PhysicsComponents {

vector<Vec3> positions;

vector<Vec3> velocities;

vector<float> masses;

};

// Update physics: sequential access

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

positions[i] += velocities[i] * dt; // Vectorizable

}

// Result: 10-50x improvement in physics update

12.4 Compiler Optimization Matrices

Compilers do matrix transformations on large arrays:

// LLVM's sparse matrix representation

// Hot arrays separated from cold metadata

struct SparseRow {

uint32_t *indices; // Column indices (hot)

double *values; // Values (hot)

uint32_t size; // Metadata (cold)

uint32_t capacity; // Metadata (cold)

};

// During SpMV (sparse matrix-vector multiply):

// indices and values accessed sequentially

// size/capacity rarely touched

// Further optimization: indices and values interleaved

// for better prefetching in some access patterns

12.5 Network Packet Processing

High-performance networking optimizes for cache:

// DPDK packet buffer structure

// Designed for cache efficiency

struct rte_mbuf {

// First cache line (64 bytes) - hot path

void *buf_addr;

uint16_t data_off;

uint16_t data_len;

uint32_t pkt_len;

// ... other hot fields

// Second cache line - less frequent access

struct rte_mbuf *next;

uint16_t nb_segs;

// ... metadata

// Remaining lines - rarely accessed

uint64_t timestamp;

// ... debugging info

};

// Packet headers also aligned for single-line access:

// Ethernet (14) + IP (20) + TCP (20) = 54 bytes

// Fits in one cache line with minimal padding

13. Debugging Cache Performance Issues

13.1 Identifying Cache Problems

Common symptoms of cache issues:

Symptom: Code runs slower than expected

Possible cache causes:

├─ Working set exceeds cache size

├─ Poor access patterns (strided, random)

├─ False sharing in multithreaded code

├─ Structure layout causing extra misses

└─ Unintended memory allocator behavior

Symptom: Performance varies between runs

Possible cache causes:

├─ ASLR changing alignment

├─ Different initial cache state

└─ Memory allocator placing data differently

Symptom: Adding threads makes it slower

Possible cache causes:

├─ False sharing

├─ Cache line bouncing between cores

└─ L3 contention

13.2 Profiling Tools Comparison

# perf: Quick overview

perf stat -e cache-references,cache-misses ./program

# perf c2c: Find false sharing

perf c2c record ./program

perf c2c report

# cachegrind: Detailed simulation (slow but precise)

valgrind --tool=cachegrind ./program

# Intel VTune: Comprehensive analysis

vtune -collect memory-access ./program

# AMD uProf: AMD-specific insights

uprof-cli -C memory ./program

13.3 Interpreting perf c2c Output

=================================================

Shared Data Cache Line Table

=================================================

Total Hitm Snoop Remote

Index Records Lcl Hitm Hitm PA

0 4521 2341 12 198 0x7f...

HITM (Hit Modified): Cache line was modified in another cache

- High HITM = cache line bouncing between cores

- Often indicates false sharing

Drill down:

0.15% [kernel] lock_acquire

0.12% program increment_counter ← Source of contention

13.4 Cache-Aware Memory Allocators

// Standard malloc may cause cache issues:

// - Adjacent allocations may false share

// - No alignment guarantees beyond 16 bytes

// Solutions:

// 1. aligned_alloc (C11)

void *ptr = aligned_alloc(64, size); // Cache line aligned

// 2. posix_memalign (POSIX)

void *ptr;

posix_memalign(&ptr, 64, size);

// 3. Custom allocators with cache awareness

// jemalloc, tcmalloc offer better behavior

// 4. Arena allocators for related objects

struct Arena {

char *base;

size_t offset;

};

void *arena_alloc(Arena *a, size_t size) {

// Objects allocated together stay together

// Better spatial locality

void *ptr = a->base + a->offset;

a->offset += (size + 63) & ~63; // Cache line aligned

return ptr;

}

13.5 Automated Cache Optimization

// GCC/Clang provide hints:

// Prefetch hint

__builtin_prefetch(address, rw, locality);

// rw: 0=read, 1=write

// locality: 0=no locality to 3=high locality

// Structure packing

struct __attribute__((packed)) Compact {

char a;

int b;

// No padding between a and b

};

// Cache line alignment

struct __attribute__((aligned(64))) Aligned {

int data[16];

};

// Hot/cold function splitting

void __attribute__((hot)) critical_path() {

// Compiler optimizes more aggressively

}

void __attribute__((cold)) error_handler() {

// Compiler optimizes for size over speed

}

14. The Future of Caching

14.1 3D-Stacked Caches

Traditional:

┌──────────────────────┐

│ CPU Die │

│ ┌────────────────┐ │

│ │ Cores + L3 │ │

│ └────────────────┘ │

└──────────────────────┘

3D V-Cache (AMD):

┌──────────────────────┐

│ 3D V-Cache Die │ ← Additional 64MB L3

│ (stacked on top) │

├──────────────────────┤

│ CPU Die │

│ ┌────────────────┐ │

│ │ Cores + L3 │ │

│ └────────────────┘ │

└──────────────────────┘

Benefits:

- 3x more L3 capacity

- Same latency as base L3

- Significant gains for gaming, simulation

14.2 Machine Learning for Prefetching

Traditional prefetcher:

- Detects simple patterns

- Limited stride detection

- No semantic understanding

ML-based prefetcher:

- Learns program behavior

- Predicts irregular patterns

- Adapts to workload

Research examples:

- Delta-LSTM: Uses LSTM to predict address deltas

- Voyager: Graph neural network for prefetching

- Pythia: RL-based prefetching decisions

14.3 Processing Near or In Cache

Moving computation closer to data:

Near-Memory Processing:

- Logic near DRAM

- Reduces data movement

- Good for memory-bound workloads

Processing-in-Cache:

- Simple operations in SRAM

- Bit-line computing

- Reduces energy dramatically

Examples:

- AMD's newer architectures explore this

- Research: SCOPE, ComputeDRAM, Ambit

14.4 Cache Challenges in Modern Architectures

As systems become more complex, cache design faces new challenges:

Heterogeneous Computing:

- CPU and GPU share memory

- Different cache architectures must cooperate

- Coherence becomes more expensive

ARM big.LITTLE / Intel Hybrid:

- Different core types with different caches

- P-cores: Large L2, shared L3

- E-cores: Smaller L2, may share different L3

- Task migration must consider cache state

Chiplet Architectures:

- AMD Ryzen: Multiple CCDs with separate L3

- Cross-chiplet coherence adds latency

- Locality matters more than ever

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ CCD 0 │ │ CCD 1 │

│ ┌──────────┐ │ │ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ L3 │ │ │ │ L3 │ │

│ │ 32 MB │ │ │ │ 32 MB │ │

│ └──────────┘ │ │ └──────────┘ │

│ 4 cores │ │ 4 cores │

└──────┬───────┘ └──────┬───────┘

│ │

└────────┬───────────┘

│

Infinity Fabric

(higher latency)

14.5 Security Implications of Caches

Caches have been exploited in numerous attacks:

Spectre/Meltdown (2018):

- Speculative execution leaves cache traces

- Timing attacks reveal secret data

- Required fundamental CPU changes

Cache Timing Attacks:

- Measure access time to determine cache state

- Can reveal cryptographic keys

- AES T-table attacks

Prime+Probe:

1. Fill cache set with attacker data

2. Victim runs and evicts some lines

3. Attacker measures which lines evicted

4. Infers victim's access patterns

Mitigations:

- Constant-time cryptography

- Cache partitioning

- Randomized cache indexing (CEASER)

15. Summary

CPU caches are the critical technology bridging the processor-memory speed gap:

Architecture fundamentals:

- Cache lines (typically 64 bytes)

- Set-associative organization

- Multi-level hierarchy (L1 → L2 → L3)

Coherence protocols:

- MESI/MOESI maintain consistency

- Snooping detects conflicts

- False sharing causes performance issues

Writing cache-friendly code:

- Sequential access patterns

- Proper loop ordering

- Structure layout optimization

- Data-oriented design

- Loop blocking/tiling

Performance analysis:

- Use perf counters

- Measure miss rates

- Identify working set sizes

- Profile with cachegrind

Advanced techniques:

- Software prefetching

- Non-temporal stores

- Cache partitioning

- NUMA awareness

Understanding CPU caches transforms how you write performance-critical code. The difference between cache-friendly and cache-oblivious code can easily be 10-100x in performance. Profile, measure, and optimize your memory access patterns—your caches will thank you.