Database Internals: Storage Engines, Transactions, and Recovery

A deep technical walkthrough of how databases store data, ensure correctness, and recover from crashes — covering B-trees, LSM-trees, write-ahead logging, MVCC, isolation levels, and replication.

Databases are much more than SQL parsers and client libraries — their core is a storage engine that durably stores and efficiently retrieves data while preserving the guarantees applications depend upon. This article unpacks how modern databases manage on-disk data structures, coordinate concurrent access, provide transactional semantics, and recover from crashes. We’ll look at B-trees and LSM-trees, the write-ahead log, MVCC and isolation levels, recovery algorithms, and practical tuning advice for real-world systems.

1. The Database Stack: responsibilities and components

A storage engine’s main responsibilities:

- Durable storage: Persist committed transactions so they survive crashes.

- Efficient access: Serve point lookups, range scans, and index queries with low latency.

- Concurrency control: Allow multiple clients to operate safely in parallel.

- Atomicity and consistency: Ensure transactions appear atomic and preserve integrity constraints.

- Recovery: After a crash, restore a consistent state and finish or roll back in-flight operations.

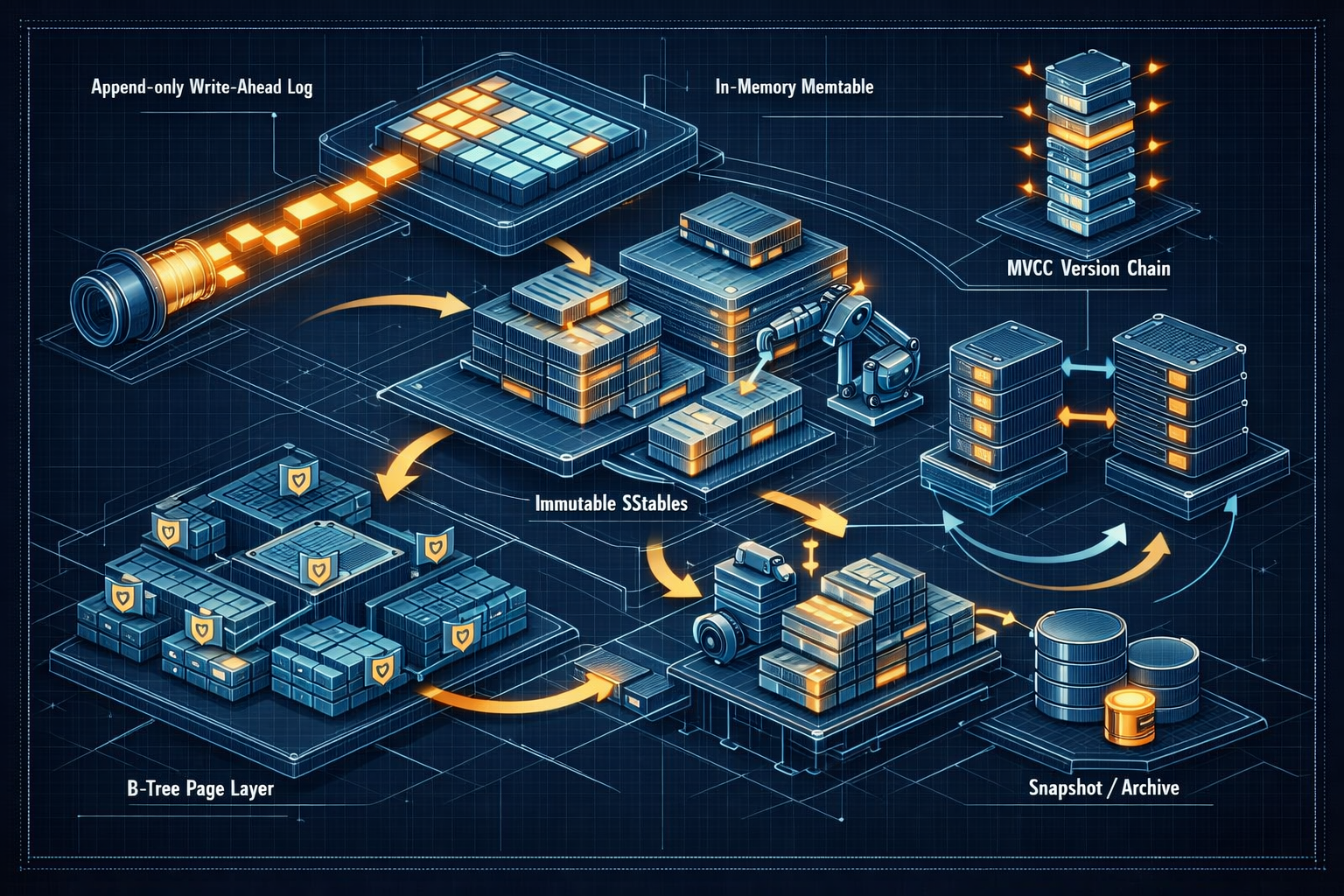

Key components:

- Write-Ahead Log (WAL): Durable sequential log of changes.

- In-memory buffers (memtables/cache): Fast read/write layer.

- On-disk structures: B-trees or SSTables which store persistent data.

- Checkpointing/compaction: Periodic actions to reduce WAL replay and rewrite data into compact form.

- Transaction manager: Tracks in-flight transactions, versions, and commit state.

- Replication & consensus: For high availability and global durability.

This layered separation allows databases to trade off read/write performance, latency, and space amplification while ensuring correctness.

2. Page-oriented storage and record layout

Most storage engines organize disk into fixed-size pages (typically 4KB or 8KB) — the unit of I/O and caching.

2.1 Typical page layout

Page header (fixed):

- Page type (leaf, interior, overflow)

- LSN (log sequence number) of last modification

- Free space pointer / slot array offset

Slot array (for variable records):

- Offsets to record beginnings (allows compaction and variable length)

Records: key, value, metadata

- Key length (varint)

- Value length (varint)

- Inline or overflow storage for big values

Page design choices affect fragmentation, scanning speed, and update complexity. For example, updates that increase record size may cause split or overflow pages, requiring extra work.

2.2 Page-based caching and dirty management

- Buffer pool: In-memory cache of recently used pages (LRU or CLOCK eviction).

- Dirty pages: Modified pages that must be flushed to disk before their WAL becomes irrelevant.

- Pinning: Prevent eviction while a page is in use.

Efficient buffer management reduces disk I/O and improves throughput.

3. B-Trees: the classic on-disk index

B-trees (and B+trees) are the canonical balanced tree used for clustered indexes and range queries.

3.1 Node structure and invariants

- Each node contains up to M keys and M+1 pointers.

- All leaves at same depth (balanced).

- Height is small for large datasets (e.g., 4–5 levels for billions of rows when page size is 4KB).

B+tree variation: keys in internal nodes, full records stored only in leaves — optimizes range scans.

3.2 Search and insert

Search complexity: O(log_M N) disk pages touched.

Insertion algorithm (high-level):

- Search down to leaf where key belongs.

- Insert key/value into leaf. If it overflows (too many keys), split.

- Propagate split to parent, possibly up to root (which can increase height).

Splitting is expensive (requires I/O to write new pages and update parent). To amortize cost, many databases batch writes or apply them via WAL before page updates.

3.3 Deletion and rebalancing

Deletion may cause underflow. Many implementations either rebalance with neighbors (borrow) or merge nodes. Rebalancing minimizes tree height changes but increases write amplification.

3.4 Locking and concurrency

Classic B-tree concurrency techniques:

- Latch coupling (hand-over-hand locking): Acquire a lock on parent, then child; release parent when child lock obtained.

- Intent locks (MDL): Indicate intention to modify a subtree so higher-level operations avoid contention.

- Lock-free or optimistic approaches: Use version counters and detect conflicts after traversals.

High-performance systems favor latch-free reads with short critical sections for structural modifications.

4. LSM-Trees: write-optimized storage engines

Log-Structured Merge Trees (LSM) invert the classic B-tree trade-offs: optimize for writes by turning random I/O into sequential writes and performing compaction in the background.

4.1 Components of an LSM engine

- Memtable: In-memory ordered structure (skiplist or tree) that accepts writes.

- WAL: Append-only log to guarantee durability of memtable contents.

- SSTables (sorted string tables): Immutable on-disk files produced by flushing memtables.

- Compaction: Background process merging multiple SSTables into new ones, discarding obsolete versions.

Flow:

- Client writes → memtable (fast) + WAL (durable).

- When memtable full → flush to SSTable (sequential write).

- Compaction merges SSTables and removes tombstones.

4.2 Read path complexity

Reads need to check memtable first, then across SSTable levels (often using bloom filters to avoid scanning files), then merge results if multiple entries exist for the same key.

SSTable layout typically includes:

- Block index (per-chunk sampling of keys)

- Bloom filter for quick negative checks

- Restart points to enable binary search inside compressed blocks

4.3 Compaction strategies and tuning

Compaction governs space amplification, write amplification, and read performance.

- Levelled compaction (used by RocksDB): Files organized in levels where each level is larger by a factor (e.g., 10). Compaction keeps levels disjoint key ranges, reducing read amplification.

- Size-tiered compaction: Merge similarly-sized files to reduce the number of files, but may increase read amplification.

Tuning knobs:

- Compaction threads and throughput throttling.

- Fanout between levels (space multiplier).

- Trigger thresholds for minor vs major compactions.

Tradeoffs:

- More compaction → lower read amplification, higher write amplification, more CPU

- Less compaction → cheaper writes, more files to consult on reads

4.4 Tombstones and delete semantics

Deletes in LSM are represented as tombstones — special marker entries. Tombstones are removed only during compaction, so reads must respect them and treat deleted keys as absent until tombstone is purged.

5. The Write-Ahead Log (WAL) and durability

WAL is the backbone of durability: a sequential record of changes that allows replay after crashes.

5.1 WAL mechanics

Principles:

- Append-only: Writes are appended to a log file and flushed to disk (fsync or fdatasync) before acknowledging commits.

- Idempotent or ordered writes: Each log record includes an LSN (log sequence number) used to order changes.

- WAL record types: Begin txn, update (page delta or key-value), commit, checkpoint markers.

On recovery, the database replays WAL records, reapplying committed changes and rolling back partial ones if necessary.

5.2 Group commit and latency amortization

Flushing the WAL per-transaction is expensive. Group commit batches multiple transactions’ WAL records before a single disk flush, amortizing fsync cost across many transactions.

Batching strategies:

- Synchronous: Wait for all transactions in group to be buffered then flush once.

- Asynchronous: Background flusher flushes WAL at regular intervals (reduces latency guarantees: producers may return before data durable).

If durability is critical (e.g., financial systems), prefer synchronous group commit with short wait windows (ms-level).

5.3 Checkpoints and reducing recovery time

A checkpoint writes a consistent snapshot of on-disk structures (pages or SSTable manifests) and records the LSN up to which recovery must replay WAL. Regular checkpoints bound recovery time by avoiding full WAL replays since inception.

6. Transactions, isolation levels, and MVCC

Transactions provide atomic multi-statement updates. Isolation levels determine how concurrent transactions interact.

6.1 ACID recap

- Atomicity: All-or-nothing semantics (often implemented using WAL and rollback).

- Consistency: Database invariants are preserved (schema, constraints).

- Isolation: Concurrent transactions do not interfere (various guarantees).

- Durability: Committed transactions survive crashes (WAL + commit flush).

6.2 Isolation levels

ANSI SQL defines several isolation levels with increasing guarantees:

- Read Uncommitted: Low isolation, may see dirty reads.

- Read Committed: No dirty reads; sees only committed data.

- Repeatable Read: Guarantees repeatable reads within a transaction (prevents non-repeatable reads), but may still allow phantoms depending on implementation.

- Serializable: Equivalent to serial execution; highest guarantee.

Databases implement these with different techniques; e.g., Snapshot Isolation (SI) is used widely because it avoids many anomalies of weaker levels while being performant.

6.3 MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control)

MVCC allows readers to see a consistent snapshot without blocking writers by keeping multiple versions of data.

Core ideas:

- Each update writes a new version with a commit timestamp or LSN.

- Reads choose the version visible to their snapshot timestamp.

- Old versions are retained until no active transactions need them (garbage collection).

MVCC data layout (simplified):

Key -> [Version: {value, commit_ts, txn_id}] -> [older versions...]

Read(snapshot_ts): find first version with commit_ts <= snapshot_ts

Write: append new uncommitted version, record in WAL

Commit: set commit_ts and flush

Read-only transactions can use a stable snapshot and never block writers — excellent for analytical queries and consistent backups.

6.4 Anomalies and SI vs Serializable

Snapshot Isolation prevents many anomalies (dirty reads, non-repeatable reads) but may allow write skew anomalies where two transactions read overlapping data and write disjoint sets producing an invalid combined state. Serializable isolation requires extra mechanisms (e.g., predicate locking, SSI — Serializable Snapshot Isolation) to eliminate such anomalies, often with higher contention.

7. Concurrency control: locking vs optimistic

7.1 Pessimistic locking

- Lock at row or page granularity (shared/exclusive modes).

- Prevents conflicting access upfront.

- Good for workloads with high write contention or long transactions.

- Deadlocks must be detected or prevented (wait-for graph and timeout-based detection).

7.2 Optimistic concurrency control (OCC)

- Transactions proceed without taking locks, validating at commit time.

- If validation fails (conflicting write), transaction aborts and must retry.

- Works well for workloads with low conflict rates and short transactions.

Validation approach:

- Read phase: Transaction reads data into local workspace, records read set.

- Validation phase: At commit, ensure no conflicting writes committed since read’s start snapshot.

- Write phase: If validation passed, apply updates (often with WAL and commit sync).

7.3 Hybrid approaches and contention mitigation

- Short transactions: OCC is effective.

- High contention: Locking or partitioning reduces aborts.

- Partition-based systems: Shard data so many transactions are single-shard and conflict-free.

8. Crash recovery: redo, undo, and checkpoints

Recovery ensures the database returns to a durable consistent state after a crash.

8.1 ARIES-like recovery (widely used)

ARIES (Algorithms for Recovery and Isolation Exploiting Semantics) is a well-known approach built around WAL and page-based logging.

Phases:

- Analysis: Read the log forward from the last checkpoint to determine the set of losers (in-flight transactions) and dirty pages.

- Redo: Reapply all logged updates from the oldest needed LSN to ensure pages are up-to-date.

- Undo: Roll back incomplete transactions by undoing their logged changes, writing compensation log records (CLRs) so undo is itself redoable.

Key properties:

- Repeating history during redo ensures idempotence: reapplying the same WAL doesn’t change correctness.

- CLRs make the undo phase safe and resumable after subsequent crashes.

8.2 Checkpointing

A checkpoint records:

- Dirty page table (which pages may have unflushed changes) and their earliest LSN.

- Transaction table (active transactions and their states).

Checkpoint frequency trades off recovery time and runtime overhead. More frequent checkpoints reduce recovery time but introduce more I/O.

8.3 Incremental and fuzzy checkpoints

- Fuzzy checkpoint: Takes a snapshot of in-memory structures without pausing the world; may require more redo work but avoids long pauses.

- Incremental checkpoint: Flushes a subset of dirty pages continuously to avoid large spikes.

9. Replication and distributed transactions

For availability and scale, databases replicate data across nodes.

9.1 Replication modes

Asynchronous (eventual): Primary applies writes and sends to replicas; commits return before replicas are durable.

- Low write latency, potential data loss if primary fails.

Synchronous: Primary waits for acknowledgment from a quorum (or all) replicas before committing.

- Higher latency, stronger durability.

Semi-synchronous: Middle ground; primary waits for at least one replica to confirm receipt but not necessarily durable.

9.2 Replication techniques

- Statement-based replication: Replicate SQL statements (hard to get deterministic behavior).

- Row-based replication: Replicate row changes directly (more reliable but larger bandwidth).

- Logical replication: Replicate logical changes (DML) with transformation capability.

9.3 Distributed transactions and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

2PC ensures atomic commits across multiple nodes:

- Prepare phase: Coordinator asks participants to prepare; participants vote YES/NO and persist a prepare record to local WAL.

- Commit phase: If all YES, coordinator asks participants to commit; otherwise, it aborts.

Drawbacks:

- 2PC blocks participants if coordinator crashes (can be mitigated with coordinator replicas or 3PC variants).

- Performance overhead: multiple network round trips and syncs.

Optimizations:

- Presumed commit/abort variants

- Combining 2PC with group commit and batching

- Using Paxos/Raft-based consensus for metadata and leader election instead of naive 2PC

10. Indexes, query patterns, and advanced storage techniques

10.1 Secondary and covering indexes

- Secondary index: Index on a non-primary key attribute; requires maintaining index on writes.

- Covering index: Contains all columns required by query; avoids lookup to primary store.

Tradeoffs:

- More indexes → faster reads, slower and heavier writes (index maintenance), increased storage.

10.2 Full-text and inverted indexes

- Inverted index maps terms to posting lists (document IDs + positions).

- Typically stored as compressed posting lists optimized for scans.

- Writes require updating multiple posting lists; often handled asynchronously or with near-real-time layers (memtables + segment merging).

10.3 Columnar storage and vectorized execution

- Column stores are optimized for analytics: store columns contiguously for compression and SIMD-friendly processing.

- Columnar storage shines for scans and aggregations, often combined with vectorized execution engines to amortize CPU overhead.

10.4 Compression and space optimization

- Compression reduces I/O and memory footprint; common techniques include prefix encoding, dictionary encoding, run-length encoding, and page-level compression.

- Tradeoffs: CPU cost for compress/decompress vs savings in IO and cache utilization.

11. Observability, metrics, and troubleshooting

Monitoring and tools are essential to diagnose performance and correctness issues.

11.1 Key runtime metrics

- Throughput (ops/sec) split by reads/writes

- Latency percentiles (p50, p95, p99, p999)

- WAL flush time and fsync latency

- Compaction throughput and queue sizes

- Number of open file descriptors and SSTable count

- Buffer pool hit rate and dirty page counts

- Transaction abort rate and average retries

11.2 Tracing and profiling

- Distributed tracing (W3C Trace, OpenTelemetry) for cross-node request flows.

- Flame graphs for CPU hotspots (compaction, WAL writing, encryption/decryption).

- Tools: perf, eBPF-based tracing, database-specific telemetry.

11.3 Debugging checklist

When investigating database anomalies:

□ Check disk and fsync latency (iostat, blktrace)

□ Inspect WAL throughput and flush latency

□ Check compaction backlog and rate

□ Monitor background threads and CPU utilization

□ Check buffer pool hit/miss ratios

□ Review recent schema/index changes

□ Search for lock contention and transaction wait graphs

□ Reproduce high-latency query with tracing enabled

□ Capture sample SSTables or pages for offline inspection

□ Verify replication lag and last-applied LSN on replicas

12. Practical tuning and best practices

A few concise guidelines for production systems:

- Choose storage engine based on workload: LSM for write-heavy workloads, B-tree for read/scan-heavy workloads with low write amplification sensitivity.

- Tune WAL group commit and commit frequency to balance latency and throughput.

- Provision enough memory for memtables and buffer pools to reduce I/O.

- Use bloom filters and adequate block sizes to optimize point reads in LSM.

- Monitor and configure compaction to avoid large backlogs; tune parallelism conservatively.

- Avoid unbounded long-running transactions; they delay MVCC cleanup and compaction.

- Use appropriate isolation level: start with read-committed or SI, move to serializable only if necessary.

13. Advanced topics and case studies

This section dives into practical, advanced topics you will encounter in production systems: consensus and leader-based replication, snapshotting and backups, corruption detection and repair, online schema evolution, and real-world engine examples.

13.1 Consensus and leader-based replication

Distributed databases commonly use a single-writer leader model for simplicity and strong consistency. Two widely-used consensus algorithms provide safe leader election and replicated logs:

- Paxos: A proven but subtle algorithm; the original formulation is complex to implement directly.

- Raft: A more engineer-friendly formulation that provides the same safety properties with clearer invariants (leader election, log replication, membership changes).

Core ideas:

- Leader election: A candidate solicits votes; the node with the most up-to-date log wins leadership.

- Log replication: Leader appends commands to its log and replicates to followers; commit is when a quorum persists the entry.

- Safety under leader changes: New leader must have the most recent committed prefix to avoid lost commits.

Practical considerations:

- Synchronous replication to a quorum provides durability guarantees even if some replicas fail but increases commit latency.

- Read-only requests can be served by followers if stale reads are acceptable, or via leader-assisted leases for safe linearizable reads.

- Membership changes (adding/removing replicas) must be done carefully to maintain quorum properties — Raft uses joint consensus for this.

13.2 Snapshots, backups, and point-in-time recovery

Backups are essential for disaster recovery and long-term retention. Common mechanisms:

- Full snapshot: Copy of data files at a point in time; fast restores but expensive to create.

- Incremental backup: Save only changed pages or SSTables since last snapshot; efficient storage but more complex restores.

- Point-in-time recovery (PITR): Use WAL segments to replay changes up to a desired LSN/ts.

Practical flow for PITR:

- Restore the latest snapshot.

- Replay WAL incrementally until the target LSN or timestamp.

- Stop recovery and open database for reads/writes at that logical point.

Storage tips:

- Keep WAL archives and snapshots reproducible and verify checksums after writing.

- Automate periodic verification of restore processes (test restores) to ensure backups are usable.

13.3 Corruption detection, checksums, and repair

Bit-rot and partial writes happen. Defenses include:

- Per-page or per-block checksums: Calculate checksums on write and verify on read.

- Doublewrite buffer (InnoDB pattern): Write page twice to disk (doublewrite area) to avoid torn-page corruption on partial page writes.

- SSTable-level checksums and corruption markers: Detect and skip corrupted files during compaction and replication.

Repair strategies:

- Replicated systems: Rebuild data from healthy replicas (preferred).

- Single-node systems: Use last-known-good snapshots, or WAL with careful replay and validation.

- Avoid in-place repairs without verification; always prefer rebuilding from verified sources when possible.

13.4 Online schema changes and backfill strategies

Schema evolution without downtime is a common requirement. Strategies:

- Expand-only changes: Add new columns with defaults handled lazily (no immediate backfill).

- Backfill in background: Add new index or compute column values with a background job that updates rows while keeping existing writes visible.

- Swap-in pointer: Create new table/index, populate it, then atomically swap metadata pointers so traffic points to the new structure.

Caveats:

- Long-running backfills can cause contention and trigger compaction or vacuum work; throttle such jobs.

- Ensure transactional visibility semantics during the transition so that readers and writers see a consistent view.

13.5 Materialized views and incremental maintenance

Materialized views (MVs) cache query results for performance. Maintenance approaches:

- Immediate update: Maintain MV on every write (strong consistency, high write cost).

- Deferred/periodic refresh: Recompute MV on a schedule (lower write cost, eventual freshness).

- Incremental maintenance: Apply diffs using change capture (WAL or change-stream) to update MVs efficiently.

Incremental maintenance needs careful handling of concurrency and ordering: use the same ordering guarantees as primary data (LSN/commit timestamps) to apply changes safely.

13.6 Security: encryption and access control

- In-transit encryption: TLS between client and server, and node-to-node encryption for replication.

- At-rest encryption: Encrypt WAL and data files with AES-GCM or similar; manage keys with KMS and rotate keys carefully.

Performance implications:

- Encryption increases CPU utilization; offloading or dedicated crypto hardware can help.

- Compression then encryption is usually optimal (compress before encrypting).

13.7 Case studies: Postgres, InnoDB, and RocksDB

Postgres (WAL/XLOG + checkpoints):

- WAL stores write-ahead records (XLOG) and is flushed on commit depending on synchronous_commit.

- Checkpoints write dirty pages to reduce WAL replay on recovery; checkpoint tuning affects both runtime I/O and recovery time.

InnoDB (doublewrite + clustered B-tree):

- InnoDB uses a clustered B+tree for primary tables and a doublewrite buffer to prevent torn pages.

- It also supports change buffering (insert buffering) to defer random writes and improve throughput.

RocksDB (LSM + compaction):

- RocksDB exposes many knobs: memtable size, block size, bloom filters per level, compaction style, and compaction threads.

- It offers universal/levelled/leveled-compaction tradeoffs; tuning requires workload profiling.

13.8 Multi-region and global considerations

Designing for geo-distribution introduces new tradeoffs:

- Latency vs consistency: Synchronous replication across regions increases commit latency dramatically; asynchronous or CRDT-based approaches offer lower latency with weaker consistency.

- Data locality: Route requests to nearest replicas when possible, but be mindful of stale reads.

- Failover automation: Automate leader failover with clear health checks to avoid split-brain.

13.9 Repair and resilience patterns

- Self-healing replicas: Nodes detect corruption and request fresh data from healthy peers.

- Read repair: On reads, detect divergence and schedule repairs.

- Re-replication: Maintain redundancy factor by re-copying missing or corrupted shards.

13.10 MVCC garbage collection and vacuum strategies

MVCC requires periodic cleanup of old versions to reclaim space and reduce read amplification.

- Conservative vacuuming: Only remove versions when no transaction can possibly need them (safe but may accumulate bloat).

- Aggressive vacuuming: Reclaim space quickly to reduce storage/bloat at the cost of more CPU and IO.

Postgres example:

- Autovacuum scans tables based on update/delete-rate heuristics and triggers VACUUM to reclaim dead tuples.

- Long-running transactions prevent tuple removal (because their snapshot might still need old versions), causing table bloat and higher autovacuum costs.

Practical tips:

- Monitor long transactions (pg_stat_activity in Postgres) and alert on transactions older than acceptable thresholds.

- Tune autovacuum thresholds and scale-up autovacuum workers if you have high update rates.

- For LSMs: large numbers of tombstones delay compaction; tune compaction and reduce tombstone retention windows.

13.11 Global ordering and timestamp allocation (Spanner-style)

Systems like Google Spanner provide externally-consistent distributed transactions by using a tightly synchronized time API (TrueTime) to assign timestamps.

Key points:

- TrueTime provides an interval [earliest, latest] for the current physical time, allowing servers to assign conservative commit timestamps that respect causality.

- If a leader assigns a commit timestamp, it may delay commit until the latest allowed time has passed to avoid anomalies — this can add latency but simplifies correctness.

If you don’t have a global clock, logical clocks (Lamport or hybrid logical clocks) plus conservative protocols can be used, but they complicate external consistency guarantees.

13.12 Sagas and application-level compensation

Not all distributed business workflows require ACID across services. Sagas are a pattern for long-lived distributed operations using compensating actions:

- Each step is a local transaction; if any step fails, run compensating transactions on completed steps to undo effects.

- Requires idempotent compensating actions and careful ordering.

Use-cases:

- Multi-service order fulfillment where each microservice commits locally, and occasional compensating refunds are acceptable.

- When acceptably eventual correctness and high availability trump strict atomicity.

13.13 Benchmarking and realistic load testing

Synthetic microbenchmarks are useful for isolating parts of the stack, but realistic testing must mirror production workloads. Key considerations:

- Use representative data sizes, distributions (zipfian, uniform), and operation mixes (read/write ratio).

- Measure latency percentiles (p50/p95/p99/p999), not just averages.

- Include background tasks (compaction, checkpoint) in test to measure interference.

Tools and commands:

YCSB for key-value workloads: tune thread count, request distribution, and record count.

sysbench for OLTP-like workloads on MySQL/Postgres:

sysbench oltp_read_write –threads=128 –time=600 –tables=32 –table-size=100000 run

For RocksDB: built-in db_bench with options for writes, compaction threads, and bloom filters.

Interpretation:

- A slight throughput increase with a big latency tail (p99 spike) often signals contention or background work. Investigate blocking activities (fsync, compaction) at those times.

- Long tail latencies deserve attention even if average latency is acceptable.

13.14 Practical recovery walkthrough (example)

A high-level recovery flow for a crashed primary:

- Failover orchestration: Coordinator promotes a healthy replica (ensure it has recent LSN and is consistent).

- Recover crashed node: Restore last known-good snapshot, replay WAL logs to catch up to a safe LSN, run consistency checks.

- Re-join as a replica: Begin streaming WALs from new leader and confirm replication lag returns to low levels.

Commands (example for Postgres):

- Inspect WAL and checkpoints:

pg_controldataandpg_waldump(orpg_walhelpers). - Restore from base backup:

pg_basebackupfollowed by WAL replay or usingpg_restorefor logical backups.

For RocksDB:

- Use

ldb/sst_dumpfor inspecting SSTables andrepairto rebuild if metadata is inconsistent (prefer rebuilding from healthy replicas if possible).

13.15 Final notes on operational hygiene

- Automate recovery drills and test restores frequently.

- Keep WAL archives for the retention window required by compliance and business needs.

- Make configuration changes with canary rollouts to observe effects before global rollout.

14. Final checklist and best practices

A condensed checklist to run through during diagnosis or design:

- Architecture: Is the chosen storage model (LSM vs B-tree) aligned with the workload?

- Durability: Are WAL flush and replication settings enforcing your durability goals?

- Concurrency: Are transaction length and isolation tuned to avoid long-lived snapshots?

- Observability: Do you capture WAL, compaction, and checkpoint metrics and alerts?

- Backups: Do you have automated, tested snapshots and WAL archival for PITR?

- Corruption handling: Are checksums, replication health, and repair workflows defined and tested?

A condensed checklist to run through during diagnosis or design:

- Architecture: Is the chosen storage model (LSM vs B-tree) aligned with the workload?

- Durability: Are WAL flush and replication settings enforcing your durability goals?

- Concurrency: Are transaction length and isolation tuned to avoid long-lived snapshots?

- Observability: Do you capture WAL, compaction, and checkpoint metrics and alerts?

- Backups: Do you have automated, tested snapshots and WAL archival for PITR?

- Corruption handling: Are checksums, replication health, and repair workflows defined and tested?

15. Summary and final thoughts

Database internals are a rich collection of engineering solutions designed to make storage fast, available, and correct. From the micro-optimizations inside a page to the global tradeoffs of cross-region replication, every design choice has measurable consequences. By understanding these mechanisms — WAL, memtables, SSTables, B-trees, MVCC, compaction, checkpoints, and consensus — you can make informed design and operational decisions that meet your application’s needs.

15.1 Quick troubleshooting checklist

□ Is WAL flush latency high?

□ Are compaction threads saturated?

□ Are there many long-running transactions preventing cleanup?

□ Is replication lag growing on any node?

□ Are buffer pool misses causing excessive disk reads?

□ Are fsyncs or disk I/O the limiting factor?

□ Do you have automated, tested restores from snapshots and WAL?

With these advanced topics and practical checklists you should be equipped to reason about database behavior under load, tune storage systems for your workloads, and design resilient architectures for production use.