Distributed Systems: Consensus, Consistency, and Fault Tolerance

Fundamentals of distributed systems: failure models, consensus algorithms (Paxos, Raft), CAP theorem, consistency models, gossip, membership, CRDTs, and practical testing strategies like Jepsen.

Distributed systems are deceptively simple to describe and maddeningly difficult to build. When a single process is replaced by a collection of cooperating processes that communicate over unreliable networks, familiar assumptions break: partial failure becomes the norm, time is not globally synchronized, and correctness requires making explicit trade-offs. This post covers the foundations you need to reason about building correct, robust, and performant distributed systems: failure models, consensus and leader election, replication and consistency models, gossip and membership, CRDTs for conflict-free replication, testing strategies (including Jepsen-style fault injection), and operational best practices.

1. Definitions and failure models

Before designing systems, be explicit about the failure assumptions.

1.1 Process failure modes

- Crash-stop: Node halts and does not recover without external action. This is the simplest failure model and the basis for many algorithms.

- Crash-recovery: Node can crash and later rejoin, possibly with partial state or after a restart. Requires durable logs for recovery.

- Byzantine failures: Arbitrary (malicious or arbitrary) behavior — requires specialized protocols (PBFT, quorum systems with signatures).

Most practical systems assume crash-recovery or crash-stop, and treat Byzantine failures as out-of-scope.

1.2 Network failures

- Packet loss: Messages dropped due to congestion or errors.

- Delay and reordering: Messages may arrive late or in a different order.

- Partition: Network splits the cluster into disjoint sets that cannot communicate.

Design for asynchrony: don’t assume bounded message delivery times; instead design protocols that make progress when the network restores connectivity.

1.3 Timing assumptions

- Synchronous model: Bounded message delay and processing time. Strong but unrealistic in many environments.

- Eventually synchronous model: System may be asynchronous for some time but becomes synchronous later (used by many consensus proofs).

- Asynchronous model: No timing guarantees—used for impossibility results like FLP.

The FLP impossibility result states that in a purely asynchronous system with even a single crash failure, deterministic consensus cannot be guaranteed. Practical consensus algorithms therefore rely on randomness, timeouts, and leader-based optimizations to make progress in the common case.

2. Safety vs Liveness and the CAP theorem

Two fundamental properties when designing distributed algorithms:

- Safety: “Nothing bad happens” — e.g., strong consistency properties like linearizability or serializability.

- Liveness: “Something good eventually happens” — e.g., the system makes progress (commits, responds).

Designs trade these properties: during partitions, systems might sacrifice liveness for safety (reject writes) or vice versa (accept writes but risk conflicts/lost updates).

CAP theorem (Brewer): In the presence of a network partition, a distributed system must choose between consistency (C) and availability (A). This often maps to practical trade-offs:

- CP systems: Maintain consistency, reject or block requests during partitions (e.g., leader-based Raft with strict quorums).

- AP systems: Allow reads/writes during partitions but need reconciliation/merge strategies (eventual consistency, CRDTs).

CAP is a coarse guideline — modern systems reason in terms of stronger consistency models (linearizability, causal consistency) and more nuanced availability metrics (latency percentiles, staleness windows).

3. Replication strategies and consistency models

Replication gives durability and scale; how you replicate dictates consistency semantics.

3.1 Primary-replica (leader) replication

- One node acts as leader (primary) and serializes writes.

- Followers replicate the leader’s log and serve reads either synchronously or with lag.

Pros:

- Simple to reason about for strong consistency (leader linearizes writes).

- Efficient single-writer paths with batching.

Cons:

- Leader is a single point of write contention and potential availability bottleneck.

- Failover requires leader election and catch-up.

3.2 Leaderless replication (gossip/quorum)

- Writes are sent to multiple replicas and considered successful when a quorum ack is received.

- Systems like Dynamo-style designs use vector clocks or logical timestamps to detect and reconcile conflicts.

Pros:

- High availability and lower write latency if quorum is small.

- No single leader bottleneck.

Cons:

- Conflict resolution often pushed to application or via anti-entropy.

- Harder to provide strong semantics like linearizability.

3.3 Consistency models overview

- Linearizability: Single global order respecting real-time. Strongest model for single-object operations.

- Sequential consistency: Operations appear in some global order consistent across processes, but may not respect real-time.

- Causal consistency: Preserves causality; concurrent writes can be seen in different orders if causally independent.

- Eventual consistency: If no new updates, replicas eventually converge.

Most production systems choose a middle ground. For example, Spanner provides external consistency (linearizability across distributed transactions) using synchronized clocks; Cassandra offers tunable consistency (quorum reads/writes) with tunable latency/consistency tradeoffs.

4. Consensus and leader election

A central primitive for consistent replication is consensus: agreeing on a value (e.g., the next log entry) across a group of nodes despite failures.

4.1 Consensus problem

Consensus requires three properties:

- Agreement: All non-faulty processes agree on the same value.

- Validity: If all propose the same value, that value is chosen.

- Termination (Liveness): All non-faulty processes eventually decide.

Practical consensus algorithms implement safety at all times and aim for liveness under stable leader conditions.

4.2 Paxos (single-decree and multi-Paxos)

Paxos (Lamport) describes a protocol for achieving consensus via prepare and accept phases. Multi-Paxos amortizes leader election costs: after a stable leader is elected, the leader can propose a sequence of commands with fewer round trips.

Key ideas:

- Phases: Proposer sends Prepare(n); Acceptors respond with promises including any previously accepted value; if the proposer gets a majority it sends Accept(n, value); acceptors accept and persist the value.

- Unique proposal numbers ensure newer proposals supersede older ones.

4.2.1 Paxos walk-through and multi-Paxos optimization

Walk-through (single-decree Paxos):

- Proposer P chooses a proposal number n and sends Prepare(n) to all Acceptors.

- Each Acceptor that hasn’t promised a higher-numbered proposal replies with a Promise(n) and includes any previously accepted value with the highest proposal number.

- If P receives promises from a majority, it selects the value with the highest-numbered accepted proposal (if any), or its own value otherwise, and sends Accept(n, value) to the Acceptors.

- Acceptors persist the accepted value and reply Accepted.

- Once a majority of Acceptors have accepted, the value is chosen and learners are informed.

Multi-Paxos optimization:

- A stable leader can skip the Prepare phase for subsequent instances and directly send Accept(leader_term, value) for new slots, greatly reducing the number of message RTTs for each decision.

- Leader changes still require a Prepare phase to re-establish safety.

Practical pitfalls:

- Implementations must carefully handle leader changes, dropped messages, and duplicates.

- Garbage-collecting old instances and snapshotting state are necessary for practical deployments.

4.2.2 Paxos failure scenario (split acceptors)

A simple failure mode illustrates why majority quorums are required:

- Proposer P1 issues Prepare(1) and gets promises from a majority including acceptor set {A, B, C}.

- P1 sends Accept(1, v1) and gets acks from {A, B} (majority) — v1 chosen.

- Later, P2 with higher number 2 sends Prepare(2) but due to network conditions only reaches acceptor C and D (not a majority), so it doesn’t get sufficient promises to proceed.

- P2 retries or times out and may cause more message exchange, but because P1’s value v1 was accepted by a majority, any proposer that obtains a majority of promises must use v1 as its chosen value — Paxos safety prevents two different values from both being chosen.

Lessons:

- Progress requires liveness assumptions (leaders getting majority support).

- Handling minority partitions requires timeouts and retries; multi-Paxos reduces per-instance overhead once a stable leader is present.

Although Paxos is the theoretical foundation, many production systems prefer Raft or Paxos variants that explicitly encode leader behavior to simplify implementation and reasoning.

4.3 Raft: understandable consensus

Raft rephrases consensus with clearer invariants: leader election, log replication, and membership changes.

Components:

- Terms: Incrementing epochs used to ensure a single leader per term.

- Leader election: Followers vote for a candidate during election timeouts.

- Log replication: Leader appends and replicates entries, commits them when a quorum acknowledges.

- Safety: Raft ensures a leader’s log contains all committed entries by ensuring leaders are up-to-date during election.

Raft gained adoption due to its readability and robust reference implementations (etcd, Consul).

4.4 Raft internals: leader state, replication, and commit rules

A deeper look at the data structures and invariants that make Raft work in practice.

Leader state (per follower):

- nextIndex[f] : The index of the next log entry the leader will send to follower f.

- matchIndex[f] : The highest log index known to be replicated on follower f.

Replication algorithm (simplified):

- Leader receives client command and appends entry to its local log at index i.

- Leader sends AppendEntries RPCs to followers, including the previous log index/term and the new entries.

- Follower validates the prevLogIndex/prevLogTerm; if it matches its local log, it appends entries and replies success.

- On successful replication to a majority, the leader updates matchIndex and can consider the entry committed.

Commit rule:

- A leader may mark an entry at index i as committed when i is stored on a majority of servers and the entry is in the leader’s current term (this avoids committing entries from previous terms that could cause safety issues during leader changes).

- Once committed, the leader applies the entry to the state machine and returns success to the client.

Pipelined replication and batch append:

- Leaders send multiple AppendEntries in flight to keep followers’ IO busy.

- Batching many small client requests into one log append amortizes per-request overhead and fsync costs.

Snapshotting and log compaction:

- When the log grows large, the leader can take a snapshot of the current state machine and discard old log entries up to the snapshot index.

- Followers that are far behind can install snapshots rather than fetch long histories.

Failure scenario (example):

- Leader L appends entries 101–110 but a network partition prevents L from replicating them to a majority.

- A new leader L2 is elected from a partition containing a majority whose logs end at index 100.

- Once L2 becomes leader, L’s entries 101–110 are not considered committed; L will either be deposed or its entries will be overwritten when it rejoins and syncs with the new leader’s log.

Recovery and durability:

- Logs must be persisted to stable storage before acknowledging a commit if you require durability across crashes.

- Snapshotting reduces recovery time by allowing a restarted node to install the latest snapshot and then fetch only subsequent entries.

4.5 Optimizations and practicalities

- Leader stickiness and leases minimize elections by keeping the same leader active while the network is healthy.

- Batching entries and using pipelined replication improves throughput by keeping disks and network saturated.

- Log compaction snapshots reduce storage of historical entries and accelerate recovery for newly promoted or restarted replicas.

4.6 Raft timeline example (detailed)

A concrete timeline helps understand corner cases. Consider a cluster A, B, C with A as leader.

T0: A’s current term is t. A has committed entries up to index 100.

T1: Client writes entry 101 to leader A. A appends it to its log and sends AppendEntries(101) to B and C.

T2: Network partition prevents messages to B; C receives and appends 101 and replies success. A receives reply from C and has majority (A and C) — it marks 101 committed and applies it to the state machine, returning success to client.

T3: A becomes isolated from majority and is partitioned alone.

T4: B and C remain connected. B times out, becomes candidate for term t+1, and requests votes. C votes for B if B’s log is at least as up-to-date as C’s. If B gets majority, B becomes leader and starts appending entries at term t+1.

T5: Because A’s entry 101 was committed on a majority (A and C) when A was leader, safety requires that any future leader’s log contains 101; the election protocol ensures this because C, which has 101, will only vote for candidates with logs at least as up-to-date.

Key takeaways:

- Committing requires majority replication; once committed, entries survive leader changes.

- Partition-tolerant designs prevent two different values from being committed simultaneously by enforcing majority quorums and log-up-to-date checks during elections.

5. Failure detectors and membership

Consensus and replication rely on accurate membership information. Failure detection is inherently unreliable in asynchronous systems and requires careful design.

5.1 Heartbeating and accrual failure detectors

- Simple detector: Missing heartbeats after a timeout signals a failure (but timeouts are unreliable in overloaded networks).

- Phi accrual detector: Computes a suspicion level (phi) based on historical heartbeat inter-arrival times; offers tunable sensitivity.

Trade-offs:

- Aggressive timeouts: Fast detection but higher false positives (causing unnecessary elections).

- Conservative timeouts: Fewer false positives but slower to react to real failures.

5.2 Membership changes and reconfiguration

- Replacing nodes must preserve quorum invariants; joint-consensus (as in Raft) transitions membership safely.

- Rolling upgrades require careful sequencing to avoid violating majority requirements.

6. Anti-entropy and gossip protocols

Gossip-based protocols provide scalable dissemination, membership, and anti-entropy (eventual convergence) in large clusters.

6.1 Gossip basics

- Nodes periodically select random peers and exchange state digests (e.g., vector clocks, version vectors, hash summaries).

- These pairwise exchanges eventually spread updates to entire cluster (probabilistic guarantees).

Advantages:

- Scales to thousands of nodes with gentle load distribution.

- Resilient to partial failures and network churn.

Disadvantages:

- Probabilistic convergence time and potential temporary inconsistency.

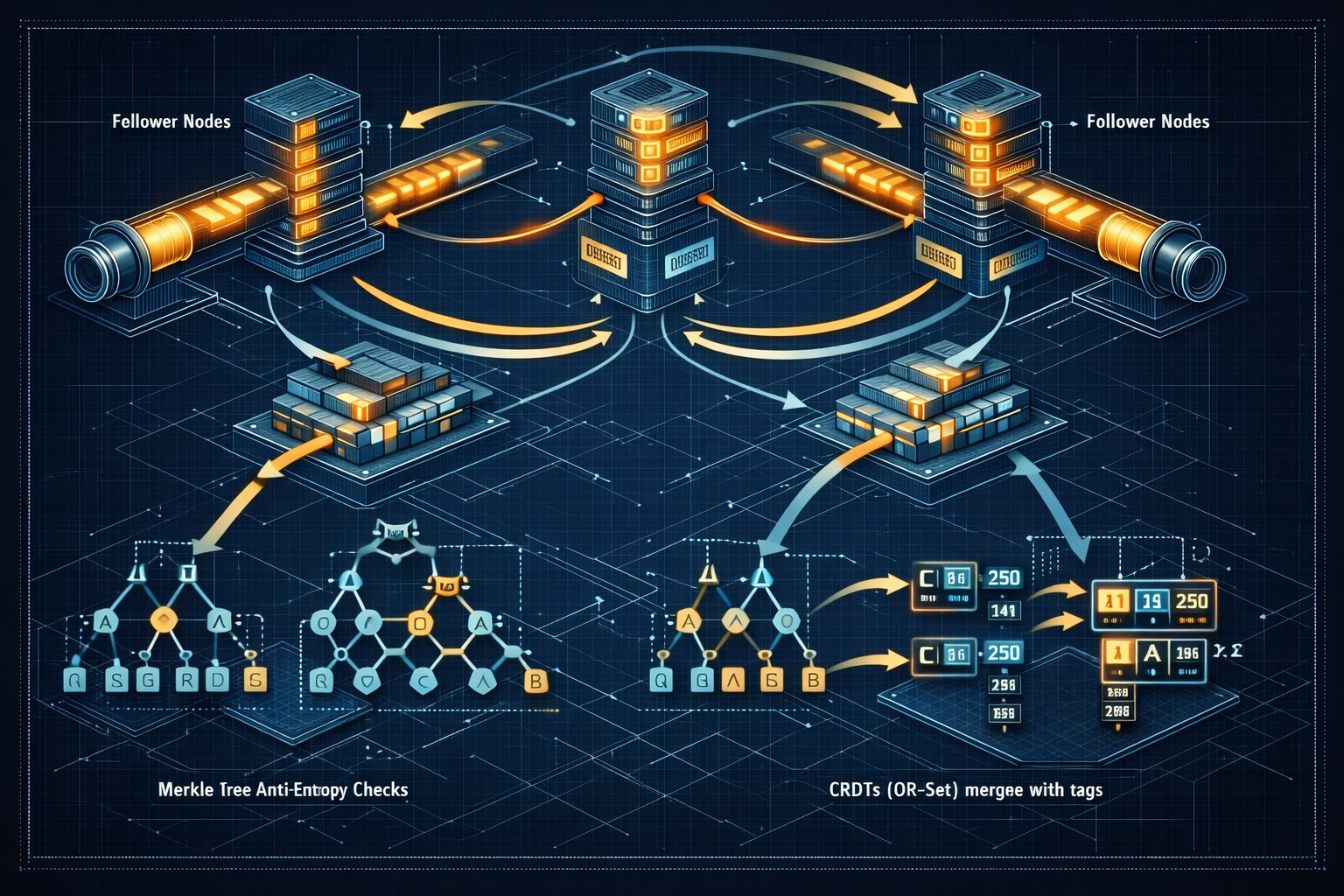

6.2 Anti-entropy and Merkle trees

- Merkle trees allow efficient detection of differences between replicas by comparing hash roots and recursing into divergent subtrees.

- Widely used in distributed databases and peer-to-peer systems for efficient synchronization.

7. Causality, vector clocks, and versioning

Tracking causality helps with conflict resolution and determining whether two updates are concurrent.

7.1 Vector clocks

- Each node maintains a vector of counters; when sending an event, it includes a copy.

- Merge and compare operations determine causal relationships: a ≤ b if every component is ≤.

Vector clocks solve causality detection but grow in size with number of participants; practical systems often use compacted or approximate versions.

Example:

Three nodes A, B, C start with vectors [0,0,0].

A writes x → A increments its counter: A: [1,0,0], sends event with vector [1,0,0].

B reads x (gets vector [1,0,0]) then writes y → increments its counter: B: [1,1,0] (merging read vector), sends event with [1,1,0].

C concurrently writes z without seeing A or B: C: [0,0,1].

Comparisons:

- [1,1,0] and [0,0,1] are concurrent (neither ≤ the other); conflict detected.

Practical considerations:

- Vector clocks must be compacted (pruning old entries or using coarse-grained membership) to avoid unbounded growth.

- In large clusters, CRDTs or HLCs are often preferred for scalability.

7.2 Hybrid logical clocks

- HLCs combine physical time with logical counters to bound skew and provide causality without keeping full vectors. Useful for systems that require causality plus compactness (e.g., Spanner/HLC variants).

8. Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs)

CRDTs provide deterministic, mergeable data types that converge without coordination.

- State-based (convergent) CRDTs: Each replica periodically sends its full state; merging is commutative, associative, and idempotent.

- Operation-based (commutative) CRDTs: Send operations that are guaranteed to commute under delivery order assumptions.

Examples:

- G-Counters (grow-only), PN-Counters (positive/negative), LWW-Register (last-writer-wins), OR-Set (observed-remove set).

7.3 OR-Set (Observed-Remove Set) example

OR-Set stores add and remove operations with unique tags so removes only affect observed adds. A simple implementation:

State example:

adds: map from element → set of tags (e.g.,adds['x'] = {t1, t2})removes: map from element → set of tags observed at remove time

Operations:

add(e): generate unique tagt, doadds[e].add(t)remove(e):removes[e] |= adds[e](record tags observed at remove time)lookup(e): present ifadds[e] \ removes[e] != ∅

Merge (state-based): union the adds and removes maps (element-wise union of tag sets). The set converges because unions are commutative, associative, and idempotent.

Example:

- Replica A:

add(x)with tagt1→adds[x] = {t1} - Replica B:

add(x)with tagt2→adds[x] = {t2} - If B removes

xbefore seeingt1:removes[x] = {t2} - Merge:

adds[x] = {t1,t2},removes[x] = {t2}→ present because{t1,t2} \ {t2} = {t1}

OR-Sets allow removes without coordination and avoid classic lost-delete anomalies.

CRDTs are powerful when you need high availability and eventual consistency without complex conflict resolution.

9. Distributed transactions and atomic commit

Transactions spanning multiple nodes are expensive and require careful protocols.

9.1 Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

- Coordinator asks participants to prepare and persist the prepared state (voting phase).

- If all vote yes, coordinator sends commit; otherwise, abort.

2PC blocks participants waiting for the global decision if coordinator fails — several variants and optimizations exist, including presumed commit/abort and participant involvement in coordinator recovery.

9.1.1 Transaction commit path (WAL, replication, and durability)

A typical distributed commit path with WAL and replication looks like this:

- Client submits transaction to coordinator which assigns a transaction id and begins distribution.

- Coordinator sends prepare requests to participants; each participant writes a “prepare” record to its WAL and fsyncs to durable storage before replying prepared.

- When coordinator receives prepared ACKs from a quorum (or all, depending on policy), it writes a commit record to its WAL and broadcasts commit messages.

- Participants apply the commit, make changes durable, and acknowledge commit to the coordinator.

- Coordinator returns success to client once durability guarantees are satisfied (either after coordinator WAL flush or after participant commit ACKs per chosen durability semantics).

Notes:

- Durability depends on where and when fsyncs happen; syncing only the coordinator may lead to data loss if the coordinator crashes before replication completes.

- Group commit and batching reduce latency by amortizing fsync costs across many transactions.

- Optimizations such as ‘presumed commit’ reduce log records in the common case but complicate recovery bookkeeping.

Drawbacks and mitigations:

- Participants may remain blocked in prepared state when the coordinator crashes; recovery protocols or coordinator replication can mitigate blocking by electing a recovery coordinator.

- Using consensus (e.g., Raft) to replicate a commit decision reduces single-coordinator blocking at the cost of additional complexity.

9.2 Three-Phase Commit (3PC) and non-blocking variants

3PC aims to be non-blocking under certain failure assumptions by adding an extra phase and requiring additional timing properties; in practice, it is less commonly used due to complexity and stronger timing assumptions.

9.3 Distributed transactions with consensus

- Some systems implement distributed transactions using Paxos/Raft for ledger replication and use consensus to serialize commit decisions (e.g., Calvin, Spanner’s two-phase commit over timestamps).

- Optimistic snapshot isolation and partitioning reduce cross-node coordination.

9.4 Sagas and compensation

Sagas break distributed updates into a sequence of local transactions with compensating actions to undo effects when later steps fail — a pragmatic pattern for long-running workflows.

10. Testing and fault injection

Reality is harsh: adopt chaos engineering and formal tests to gain confidence.

10.1 Jepsen-style testing

Jepsen injects network partitions, process kills, and clock skew and verifies correctness properties (linearizability, snapshot isolation) under stress. It has uncovered subtle bugs in many distributed systems.

10.2 Model checking and systematic exploration

- Tools like TLA+, PlusCal, and model checkers can validate protocols under exhaustive interleavings.

- State space explosion limits coverage, but these tools catch design-level errors early.

10.3 Chaos engineering and resilience testing

- Run fault injection in production-like environments: simulate partitions, disk faults, and slow networks.

- Observe system behavior, failure modes, and recovery procedures; automate and monitor rollbacks.

11. Practical optimizations and performance

Real systems add engineering to make consensus and replication practical at scale.

11.1 Batch, pipeline, and leader batching

- Aggregate multiple client requests into single log entries to amortize per-request overhead.

- Pipeline log replication to keep network and disk busy.

11.2 Log compaction and snapshotting

- Periodic snapshots of in-memory state and truncation of logs reduce recovery times and disk usage.

- Make snapshots incremental and use copy-on-write techniques to avoid long pauses.

11.3 Read optimization

- Serve weakly-consistent reads from followers for low-latency operations when freshness isn’t critical.

- Use leader lease or read-index mechanisms to serve linearizable reads without extra round trips.

11.4 Partitioning, consistent hashing, and rebalancing

Sharding and partitioning allow systems to scale horizontally, but moving data between nodes safely and efficiently is non-trivial.

Consistent hashing:

- Map keys to a hash space (e.g., 0..2^64-1) and assign nodes to points in the space.

- Each key maps to the nearest node clockwise from its hash position.

- Adding/removing a node only affects keys between the node and its predecessor, reducing data movement compared to range-based sharding.

Virtual nodes:

- Assign each physical node many virtual nodes (tokens) spread across the hash space to produce better load balance.

- Rebalancing: When a node joins or leaves, only its virtual nodes’ ranges need migrating.

Rebalancing strategies:

- Repartitioning via streaming: Move data incrementally and serve reads/writes from both source and destination during handoff.

- Throttling migration: Limit copy bandwidth to avoid interfering with normal traffic.

- Maintaining replication factor: Ensure new replicas are fully caught up before demoting a source replica to avoid data loss.

Range-based sharding (ordered by key):

- Easier for range queries since contiguous keys map to the same shard.

- Rebalancing requires splitting and moving entire ranges; often done with background copy + switch-over.

Operational concerns:

- Coordinate rebalancing with load and compaction to avoid overload.

- Use metrics for migratory throughput and lag; alert on stalled rebalances.

12. Observability, debugging, and runbooks

Metrics, traces, and playbooks are essential for operating distributed systems.

12.1 Key observability signals

- Commit latency, replication lag, leader election rates, and error rates.

- Tail latency (p99/p999) often more important than averages.

- Heartbeat/phi counts for failure detectors and their false-positive rates.

12.2 Runbooks and incident response

- Define clear runbooks for leader failover, split-brain scenarios, and unsafe reconfigurations.

- Practice recovery steps in staging and runbooks must include rollback imagers, snapshot restores, and safety checks.

13. Real-world case studies

A few systems and notable design decisions:

- Apache Kafka: Log-centric architecture with partition leaders, high-throughput replication, and pluggable consistency settings (acks=all/quorum).

- Google Spanner: Global transactions with TrueTime-synchronized timestamps enabling external consistency.

13.1 Spanner and TrueTime (external consistency)

Spanner provides external consistency (a strong form of linearizability across distributed transactions) by relying on tightly synchronized clocks and a time API called TrueTime that returns an interval [earliest, latest] capturing clock uncertainty.

Key protocol:

- When committing a transaction, Spanner assigns a commit timestamp greater than any read timestamp previously observed and waits until the TrueTime

earliestexceeds that timestamp (or specifically untillatest < commit_timestamp), ensuring no causally later events can have an earlier timestamp — this wait is the commit-wait, and it uses physical time to make transactions appear serialized in global time.

Trade-offs:

- Achieves very strong consistency semantics, simplifying application reasoning at the cost of increased commit latency (the commit-wait) and the operational burden of maintaining low clock uncertainty (GPS/atomic clocks or specialized synchronization).

- If clock uncertainty is large, commit-waits increase and throughput can suffer.

Hybrid logical clocks (HLC) and other techniques attempt to approximate some of these guarantees with less operational complexity, but TrueTime provides a clean model for external consistency when you can invest in clock infrastructure.

Cassandra: Tunable consistency with gossip-based membership and hinted handoff for temporary failures.

etcd/Consul: Use Raft for strong consistency and leader-based coordination for service discovery and configuration storage.

14. Checklist and best practices

Quick checklist for architects and operators:

- Define your consistency SLA and failure model explicitly.

- Choose replication style (leader vs leaderless) based on workload and operational complexity.

- Use consensus for metadata and configuration — avoid using distributed consensus for every write unless necessary.

- Adopt formal spec/model checking for core consensus and membership protocols.

- Run chaos experiments and Jepsen-style tests regularly.

- Monitor tail latencies, election rates, and long-running heartbeats.

- Automate backups, snapshot restores, and recovery drills.

15. Worked example: partition with conflicting writes (timeline and resolution)

Consider a 3-node cluster A, B, C configured with Raft (leader-based) and a client performing writes:

- Leader is A. Client writes key k -> A appends entry and replicates to B, C, but due to a network partition A cannot reach B, only C.

- A replicates to C and receives a majority ack (A and C), commits the entry and replies success to the client.

- A’s link to the majority is severed, and B and C form a partition where C is reachable to B and elect C as new leader (if B has higher logs); or if B and C can’t form a majority, leader election may stall.

- If C becomes leader and a client writes a conflicting value for k to C, that value may be committed on the other partition depending on quorum; when partitions heal, Raft’s log safety ensures only one value is committed across a majority — conflicting entries from deposed leaders are overwritten.

How different systems handle this:

- CP (Raft/Paxos): Enforce majority quorums for commits. A write committed by majority cannot be revoked; split-brain scenarios where both sides think they’re leaders are prevented by quorum rules and election semantics.

- AP (Dynamo-style): Writes can be accepted in both partitions (if quorum requirement is relaxed), creating concurrent versions that must be reconciled via vector clocks, last-writer-wins, or application-specific merging.

- CRDT approach: Use commutative data types so concurrent updates automatically converge.

Resolution steps and runbook:

- Identify which entries are committed by checking the leader’s commit index and replication state on a majority.

- If conflicting replicas exist, prefer the leader with the highest term/commit index or run a repair process that reconciles last-applied states.

- If data loss risk exists (writes accepted on minority), inform affected clients and run reconciliation if necessary.

16. Jepsen-style case: a typical bug narrative

A typical Jepsen discovery path:

- Inject partitions and delayed fsyncs while running a workload with a mix of reads and writes and a client assertion for linearizability.

- Observe a linearizability violation: A read returns a value earlier than a write that was supposedly committed.

- Trace timeline: the write was acknowledged by the primary (which didn’t ensure replication durability), then primary crashed before flushing to disk; a new leader was elected without the write, causing clients to see stale state.

Lessons:

- Acknowledging writes before replication persistence or participant fsyncs can yield durability anomalies on primary crashes.

- Jepsen tests force you to decide where to place durability and replication guarantees in the write path.

17. Tuning elections, timeouts, and heuristics

Election/heartbeat tuning rules of thumb:

- Heartbeat interval (h): How often leaders send heartbeats (e.g., 50-200ms in LANs).

- Election timeout (E): Randomized between [T, 2T] where T ≈ 3-5×h to avoid live lock.

Example:

- h = 100ms, set E ∈ [300ms, 500ms] randomized per node.

Observations:

- Network jitter and GC pauses can cause spurious elections; increase E in noisy environments.

- Too-large E increases failover latency; too-small E increases election rate and instability.

Other heuristics:

- Use leader stickiness: avoid immediate re-election after transient issues by preferring an existing leader if it still holds a lease.

- Monitor election rate and correlate with GC/pause and CPU saturation to find root causes.

18. Operational commands and useful metrics

Examples (generic):

- Check cluster health and leader:

ctl cluster status(system-specific),kubectl get endpointsfor k8s services. - Check logs and term/election events:

journalctl -u your-service | grep electionor search for “Term” updates. - Inspect replication lag and pending logs: system-specific ‘replication’ or ‘queue’ commands.

- Prometheus queries:

histogram_quantile(0.99, sum(rate(request_duration_seconds_bucket[5m])) by (le))for tail latencies.

19. Further reading and resources

- Leslie Lamport’s Paxos papers

- Diego Ongaro & John Ousterhout’s Raft paper and extended thesis

- Adya’s paper on weak isolation levels

- Jepsen repository and blog posts for practical tests

- CRDT survey papers for data-type specifics

19.1 Consistency anomalies: short catalog with examples

Understanding anomalies helps pick correct isolation models:

Dirty read: Transaction reads uncommitted data written by another transaction.

- SQL examplified: T1 writes x=10 (not committed); T2 reads x and sees 10. Under Read Committed, this cannot happen.

Non-repeatable read: A transaction reads the same row twice and sees different values because another transaction committed between reads.

- T1: read x (gets 10); T2: write x=20 commit; T1: read x again → 20.

Phantom read: Range queries return different sets due to concurrent inserts/deletes.

- T1: SELECT * WHERE amount > 100 returns N rows; T2 inserts a qualifying row and commits; T1 runs the same query and sees an extra row.

Write skew: Two concurrent transactions read overlapping data and write disjoint sets, leading to invariant violation under snapshot isolation.

- Example: Two doctors on-call scheduling: both read other doctor’s schedule and both decide to go off-call, violating the constraint “always at least one doctor on-call.”

Recognizing these anomalies helps choose stricter isolation (e.g., serializable) or application-level invariants and checks.

19.2 CRDT operation-based example (op-based OR-Set)

Operation-based OR-Set sends operations instead of states:

add(e, t)sends op with unique tagt.remove(e)sends remove operation referencing observed tags or tombstones depending on protocol.

Delivered op order is guaranteed by reliable dissemination; if delivery is unreliable, the op-based approach requires stable broadcast or idempotency guarantees.

19.3 Jepsen reproduction steps (practical)

- Define the model: e.g., linearizability for a set of operations and a key subset.

- Implement client workloads that assert invariants and log operation timelines.

- Use network partitioning, clock skew, process kills, and disk stalls to create adversarial conditions.

- Run multiple iterations, collect histories, and feed them to a checker (Jepsen provides model checkers).

Sample command (conceptual):

lein run test --checkers linearizable --nemesis partition(system- and test-specific)

19.4 Performance tuning: measuring and interpreting

Use YCSB for key-value workloads: vary read/write mix and record distributions (zipfian). Example:

./bin/ycsb load cassandra-cql -P workloads/workloadc -p recordcount=1000000 -p threadcount=64Watch for high p99/p999 latencies and correlate with background tasks like compaction or GC.

When latency tails spike during compaction, consider lowering compaction IO priority or increasing compaction parallelism with careful throttling.

19.5 Security and operational hygiene

- Encrypt node-to-node traffic and client connections with TLS; enable mutual authentication for control planes.

- Audit and rotate keys (KMS) regularly; keep WAL archives encrypted.

- Limit admin APIs and use RBAC for operational controls.

20. Wrap-up

Distributed systems require trade-offs and explicit reasoning. Knowing the guarantees and costs of consensus, replication, and failure detectors lets you design systems that behave predictably under load and adversity. Use the checklists above as starting points, and invest in testing, observability, and rehearsal — the hardest bugs are the ones you haven’t yet experienced.

20.1 Debugging checklist

□ Is the system making progress (commits/ops)?

□ Did an election or configuration change occur recently?

□ Is replication lag or log backlog increasing?

□ Are timeouts and heartbeat intervals tuned for your environment?

□ Are long-running transactions or snapshots blocking progress?

□ Can you reproduce the fault with partition/kill tests in staging?