File Systems and Storage Internals: How Data Persists on Disk

A comprehensive exploration of file system architecture, from inodes and directories to journaling and copy-on-write. Understand how operating systems organize, protect, and efficiently access persistent data.

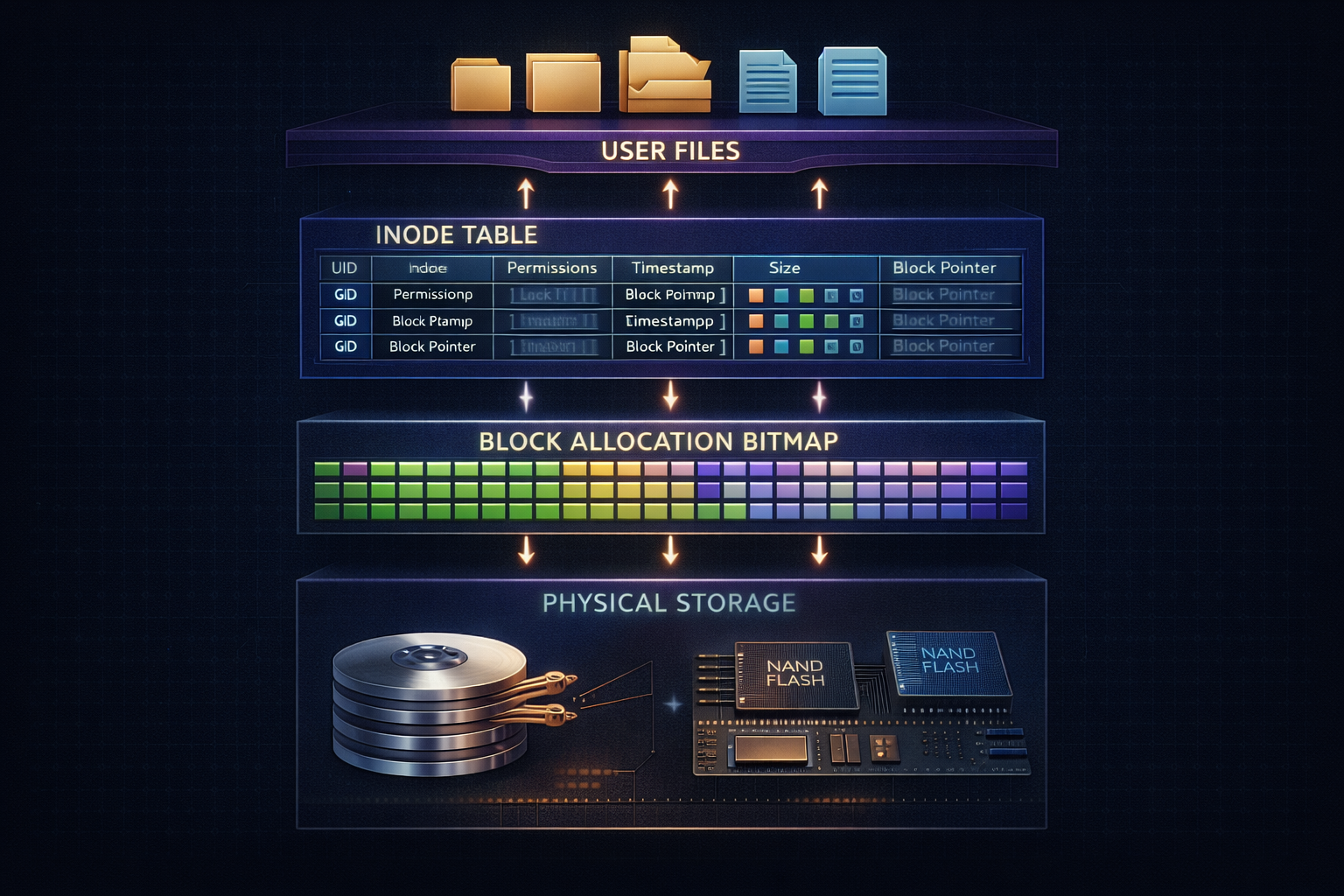

Every file you save, every application you install, every database record—all must survive power failures and system crashes. File systems provide this durability guarantee while making storage appear as a simple hierarchy of named files and directories. Behind this abstraction lies sophisticated machinery for organizing billions of bytes, recovering from failures, and optimizing access patterns. Understanding file system internals illuminates why some operations are fast and others slow, why disks fill up unexpectedly, and how your data survives the unexpected.

1. The Storage Stack

Before examining file systems, let’s understand the full storage hierarchy.

1.1 Layers of Abstraction

Application Layer:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ open("/home/user/data.txt", O_RDWR) │

│ read(fd, buffer, 4096) │

│ write(fd, buffer, 4096) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

VFS (Virtual File System):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Unified interface for all file systems │

│ inode cache, dentry cache, page cache │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

File System (ext4, XFS, btrfs):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Files → blocks mapping │

│ Directories, permissions, journaling │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Block Layer:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ I/O scheduling, request merging │

│ Block device abstraction │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Device Driver:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ SATA, NVMe, SCSI protocols │

│ Hardware-specific commands │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Physical Storage:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ HDD: Spinning platters, seek time, rotational │

│ SSD: Flash cells, FTL, wear leveling │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

1.2 Block Devices

Storage devices expose fixed-size blocks:

Traditional block size: 512 bytes (sector)

Modern devices: 4096 bytes (4K native)

File system block: Usually 4096 bytes

Block addressing:

┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ 0 │ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │ 6 │ ... │

└─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

4KB 4KB 4KB 4KB 4KB 4KB 4KB

Device capacity = block count × block size

1TB drive with 4KB blocks = ~244 million blocks

Operations:

- Read block N

- Write block N

- Flush (ensure writes hit persistent media)

- Trim/Discard (inform device blocks are unused)

1.3 HDD vs SSD Characteristics

Hard Disk Drive (HDD):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Spinning platters + moving head │

│ │

│ Seek time: 5-15ms (move head to track) │

│ Rotational latency: 2-8ms (wait for sector) │

│ Transfer: 100-200 MB/s sequential │

│ │

│ Random I/O: ~100 IOPS (dominated by seek) │

│ Sequential I/O: Much faster (no seeking) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Solid State Drive (SSD):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Flash memory + controller │

│ │

│ No moving parts, no seek time │

│ Random read: ~100µs latency │

│ Transfer: 500-7000 MB/s │

│ │

│ Random I/O: 10,000-1,000,000 IOPS │

│ Write amplification: Erase before write │

│ Wear: Limited program/erase cycles │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

NVMe SSD:

- Direct PCIe connection (no SATA bottleneck)

- Multiple queues (64K commands per queue)

- Even lower latency (~10µs)

2. File System Fundamentals

Core concepts that all file systems share.

2.1 Inodes: File Metadata

Each file has an inode containing metadata:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Inode 12345 │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Type: Regular file │

│ Permissions: rwxr-xr-x (755) │

│ Owner UID: 1000 │

│ Group GID: 1000 │

│ Size: 28,672 bytes │

│ Link count: 1 │

│ Timestamps: │

│ - atime: Last access │

│ - mtime: Last modification │

│ - ctime: Last inode change │

│ Block pointers: │

│ [0]: Block 1000 │

│ [1]: Block 1001 │

│ [2]: Block 1005 │

│ [3]: Block 1006 │

│ [4]: Block 1007 │

│ [5]: Block 1008 │

│ [6]: Block 1009 │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Note: Filename is NOT in inode!

Filename is in directory entry

2.2 Directories

A directory is a file containing name→inode mappings:

Directory /home/user (inode 5000):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Entry │ Inode Number │

├──────────────────┼───────────────────────────────┤

│ . │ 5000 (self) │

│ .. │ 4000 (parent: /home) │

│ documents │ 5001 (subdirectory) │

│ data.txt │ 12345 │

│ config.json │ 12346 │

│ script.sh │ 12347 │

└──────────────────┴───────────────────────────────┘

Path resolution for /home/user/data.txt:

1. Start at root inode (inode 2)

2. Read root directory, find "home" → inode 4000

3. Read inode 4000 directory, find "user" → inode 5000

4. Read inode 5000 directory, find "data.txt" → inode 12345

5. Read inode 12345 for file metadata

2.3 Hard Links and Soft Links

Hard link: Multiple directory entries → same inode

/home/user/file1.txt ───┐

├──► Inode 12345 ──► Data blocks

/home/user/file2.txt ───┘

Link count: 2

- Same file, different names

- Cannot span file systems

- Cannot link directories (except . and ..)

- File exists until link count = 0

Soft (symbolic) link: File containing path to target

/home/user/shortcut ──► Inode 12350 ──► "/home/user/actual/file"

│

▼

Inode 12400 ──► Data

- Points to path, not inode

- Can span file systems

- Can link directories

- Can be "dangling" if target deleted

2.4 File Holes (Sparse Files)

Files can have "holes" - unallocated regions:

Sparse file with 1MB written at offset 0 and offset 100MB:

Logical view:

┌──────────┬────────────────────────────────┬──────────┐

│ 1MB │ (hole) │ 1MB │

│ data │ ~99MB zeros │ data │

└──────────┴────────────────────────────────┴──────────┘

Offset: 0 100MB

Physical storage:

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ 1MB │ │ 1MB │

│ blocks │ │ blocks │

└──────────┘ └──────────┘

Apparent size: 101 MB

Actual disk usage: 2 MB

Creating sparse file:

fd = open("sparse", O_WRONLY | O_CREAT);

lseek(fd, 100 * 1024 * 1024, SEEK_SET);

write(fd, data, 1024 * 1024);

Reading hole returns zeros (no I/O needed)

3. Block Allocation Strategies

How file systems map files to disk blocks.

3.1 Direct, Indirect, and Doubly Indirect

Traditional Unix (ext2/ext3) inode block pointers:

Inode:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Direct blocks [0-11] → 12 × 4KB = 48KB directly │

│ Single indirect [12] → Points to block of pointers │

│ Double indirect [13] → Points to block of indirect │

│ Triple indirect [14] → Points to block of double │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Single indirect (4KB block, 4-byte pointers = 1024 pointers):

┌────────┐ ┌────────────────┐

│ Ptr 12 │───►│ Block 5000 │

└────────┘ │ ┌────────────┐ │

│ │ Ptr to 100 │ │──► Data block 100

│ │ Ptr to 101 │ │──► Data block 101

│ │ ... │ │

│ │ Ptr to 1123│ │──► Data block 1123

│ └────────────┘ │

└────────────────┘

Maximum file size with 4KB blocks:

Direct: 12 × 4KB = 48 KB

Single: 1024 × 4KB = 4 MB

Double: 1024 × 1024 × 4KB = 4 GB

Triple: 1024 × 1024 × 1024 × 4KB = 4 TB

───────

~4 TB total

3.2 Extents (Modern Approach)

ext4 and modern file systems use extents:

Extent: Contiguous range of blocks

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Start block: 10000 │

│ Length: 256 blocks │

│ Logical start: 0 │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

File mapped by few extents vs many block pointers:

Traditional (1000 blocks):

┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬─────────────────────┬────┐

│ 10 │ 11 │ 12 │ 15 │ 16 │ ... │1099│

└────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴─────────────────────┴────┘

1000 individual pointers

Extents (same file, contiguously allocated):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Start: 10, Length: 3 │ (blocks 10-12)

│ Start: 15, Length: 2 │ (blocks 15-16)

│ Start: 100, Length: 995 │ (blocks 100-1094)

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

Only 3 extent descriptors!

Benefits:

- Less metadata for large contiguous files

- Better describes sequential allocation

- Faster file operations (less indirection)

3.3 Block Allocation Policies

Goals of block allocation:

1. Locality: Related blocks should be near each other

2. Contiguity: Files should be contiguous when possible

3. Fairness: All files get reasonable placement

4. Efficiency: Minimize fragmentation

ext4 block allocation:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Block Groups: │

│ ┌─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┐ │

│ │ Group 0 │ Group 1 │ Group 2 │ Group 3 │ ... │

│ └─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┘ │

│ │

│ Each group has: │

│ - Superblock copy (or backup) │

│ - Group descriptors │

│ - Block bitmap │

│ - Inode bitmap │

│ - Inode table │

│ - Data blocks │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Allocation heuristics:

- Put file's blocks in same group as inode

- Put related files (same directory) in same group

- Spread directories across groups

- Pre-allocate blocks for growing files

3.4 Fragmentation

File system fragmentation over time:

Fresh file system:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File A ████████████ │

│ File B ████████ │

│ File C ████████████████ │

│ Free ░░░░░░░░░░░│

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

After deletions and new writes:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File A ████░░░░████████░░░░████ │

│ File D ████ ████░░░░████ │

│ File C ░░░░████████████ │

│ Free ░░░░ ░░░░░░░░░░░░ ░░░░ ░░░░░░░░│

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Impact:

- HDD: Severe (each fragment = seek time)

- SSD: Minor (no seek time, but may affect read-ahead)

Mitigation:

- Delayed allocation (wait to choose blocks)

- Pre-allocation (reserve contiguous space)

- Online defragmentation

- Extent-based allocation

4. Journaling and Crash Consistency

Protecting data integrity during crashes.

4.1 The Crash Consistency Problem

Updating a file requires multiple writes:

Adding block to file:

1. Write new data block

2. Update inode (add block pointer, update size)

3. Update block bitmap (mark block used)

What if crash occurs mid-sequence?

Scenario A: Only (1) completed

- Data written but lost (not linked to file)

- Block bitmap says free, data orphaned

Scenario B: Only (1) and (2) completed

- File points to block

- Block bitmap says free

- Block could be allocated to another file!

Scenario C: Only (2) and (3) completed

- File points to block with garbage

- File corruption!

All scenarios leave file system inconsistent.

4.2 fsck: Post-Crash Recovery

Traditional approach: Check entire file system

fsck operations:

1. Verify superblock sanity

2. Walk all inodes, verify block pointers

3. Verify directory structure

4. Check block bitmap against actual usage

5. Check inode bitmap against actual usage

6. Fix inconsistencies (lost+found)

Problems:

- Time proportional to file system size

- 1TB drive: Minutes to hours

- Petabyte storage: Days!

- System unavailable during check

Modern systems: Journaling avoids most fsck

4.3 Journaling Approaches

Write-Ahead Logging (Journaling):

Before modifying file system:

1. Write intended changes to journal

2. Commit journal transaction

3. Apply changes to file system

4. Mark transaction complete

Journal on disk:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Journal Area │

│ ┌──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬──────────┬────────┐ │

│ │ TXN 42 │ TXN 43 │ TXN 44 │ TXN 45 │ Free │ │

│ │ Complete │ Complete │ Committed│ Pending │ │ │

│ └──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴──────────┴────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Recovery after crash:

1. Read journal

2. Replay committed but incomplete transactions

3. Discard uncommitted transactions

4. Done! (seconds, not hours)

4.4 Journaling Modes

ext4 journaling modes:

Journal (data=journal):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ All data and metadata written to journal first │

│ Safest but slowest (data written twice) │

│ Guarantees: Data and metadata consistent │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Ordered (data=ordered) - Default:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Only metadata journaled │

│ Data written before metadata committed │

│ Guarantees: No stale data exposure │

│ Good balance of safety and performance │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Writeback (data=writeback):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Only metadata journaled │

│ Data may be written after metadata │

│ Risk: File may contain stale/garbage data after crash │

│ Fastest but least safe │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Mount options:

mount -o data=journal /dev/sda1 /mnt

4.5 Checkpoints and Journal Wrap

Journal space is limited (typically 128MB-1GB):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Journal │

│ ┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┐ │

│ │ 10 │ 11 │ 12 │ 13 │ 14 │ 15 │ 16 │ 17 │ 18 │ 19 │ │

│ │Done│Done│Done│ OK │ OK │ OK │ OK │NEW │NEW │ │ │

│ └────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┘ │

│ ↑ ↑ ↑ │

│ Checkpoint Commit Write │

│ (can reclaim) (must keep) pointer │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Checkpoint process:

1. Ensure old transactions fully written to main FS

2. Mark transactions as reclaimable

3. Advance checkpoint pointer

4. Space available for new transactions

Journal full = checkpoint forced = performance impact

5. Copy-on-Write File Systems

A different approach to consistency.

5.1 COW Principle

Never overwrite existing data:

Traditional (in-place update):

Block 100: [Old Data] → [New Data]

Overwritten in place

Copy-on-Write:

Block 100: [Old Data] (unchanged)

Block 200: [New Data] (new location)

Update parent pointer: 100 → 200

Benefits:

- Old data always consistent (no partial writes)

- Automatic snapshots possible

- No need for journal (COW is inherently safe)

Cost:

- Fragmentation (data scattered)

- Write amplification (must update parent chain)

5.2 btrfs Architecture

btrfs uses copy-on-write B-trees:

┌──────────────┐

│ Superblock │

│ (fixed loc) │

└──────┬───────┘

│

┌──────▼───────┐

│ Root Tree │

│ (COW) │

└──────┬───────┘

┌───────────────┼───────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ FS Tree │ │ Extent Tree │ │ Checksum Tree│

│ (files) │ │ (allocation) │ │ (integrity) │

└──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘

Write operation:

1. Write new leaf node with data

2. COW path from leaf to root

3. Atomically update superblock

4. Old tree still valid until superblock changes

5.3 Snapshots

COW enables efficient snapshots:

Before snapshot:

┌───────────┐

│ Root │

└─────┬─────┘

│

┌─────────┴─────────┐

▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ Dir A │ │ Dir B │

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │

▼ ▼

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ File 1 │ │ File 2 │

└─────────┘ └─────────┘

After snapshot (just copy root pointer):

Live: Root ─────────────────┐

│

Snapshot: Root' ────────────────┤

▼

[Same tree]

After modifying File 1:

Live: Root ──► Dir A' ──► File 1' (modified)

╲

► Dir B ──► File 2 (shared)

Snapshot: Root' ──► Dir A ──► File 1 (original)

╲

► Dir B ──► File 2 (shared)

Only changed paths duplicated!

5.4 ZFS Features

ZFS: Enterprise-grade COW file system

Key features:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Pooled Storage: │

│ Multiple disks → one storage pool │

│ File systems share pool space dynamically │

│ │

│ End-to-End Checksums: │

│ Every block checksummed │

│ Detects silent data corruption │

│ Self-healing with redundancy │

│ │

│ Built-in RAID (RAID-Z): │

│ RAID-Z1 (single parity), Z2 (double), Z3 (triple) │

│ No write hole problem (COW) │

│ │

│ Compression: │

│ LZ4, ZSTD, GZIP per-dataset │

│ Transparent to applications │

│ │

│ Deduplication: │

│ Identify duplicate blocks │

│ Store once, reference many times │

│ Memory intensive (DDT in RAM) │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

6. The Page Cache

RAM as a cache for disk data.

6.1 Read Caching

Page cache sits between file system and disk:

Application read request:

┌──────────┐

│ App │──── read(fd, buf, 4096) ────┐

└──────────┘ │

▼

┌───────────────────┐

│ Page Cache │

│ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Page: Hit! │──┼──► Return immediately

│ └─────────────┘ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Page: Miss │──┼──► Read from disk

│ └─────────────┘ │ then cache

└───────────────────┘

Cache lookup: O(1) via radix tree

Hit latency: ~1μs (memory speed)

Miss latency: ~10μs-10ms (storage speed)

Memory pressure → eviction:

- LRU-like algorithm (actually more sophisticated)

- Dirty pages written back before eviction

- Active vs inactive lists

6.2 Write Caching and Writeback

Writes go to page cache, not disk:

Application write:

┌──────────┐

│ App │──── write(fd, buf, 4096) ────┐

└──────────┘ │

▼

┌───────────────────────┐

│ Page Cache │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ Page (dirty) │ │

│ │ Modified in RAM │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ │

└───────────────────────┘

│

Writeback (later, async)

│

▼

┌───────────────────────┐

│ Disk │

└───────────────────────┘

Write returns immediately (data in RAM)

Data persists only after writeback or sync

Writeback triggers:

- Timer (default ~30 seconds)

- Dirty ratio exceeded (dirty_ratio, dirty_background_ratio)

- Explicit fsync/fdatasync

- Memory pressure

6.3 Read-Ahead

Kernel predicts future reads:

Sequential read pattern detected:

Read block 0 → Prefetch blocks 1, 2, 3, 4

Read block 1 → Already cached! Prefetch 5, 6, 7, 8

Read block 2 → Already cached! Prefetch 9, 10, 11, 12

...

Read-ahead window grows with sequential access:

Initial: 128 KB

Growing: 256 KB, 512 KB, up to 2 MB (configurable)

Benefits:

- Hides disk latency

- Converts random I/O to sequential (for disk)

- Dramatically improves sequential read throughput

Tuning:

blockdev --setra 8192 /dev/sda # Set read-ahead (sectors)

cat /sys/block/sda/queue/read_ahead_kb

6.4 Direct I/O

Bypass page cache for specific use cases:

Normal I/O:

App ──► Page Cache ──► Disk

Direct I/O (O_DIRECT):

App ──────────────────► Disk

Use cases:

- Database buffer pools (app manages own cache)

- Avoid double-buffering

- Predictable latency (no cache effects)

- Very large files (larger than RAM)

Requirements:

- Aligned buffers (typically 512 or 4096 bytes)

- Aligned offsets

- Aligned lengths

fd = open("file", O_RDWR | O_DIRECT);

// Buffer must be aligned:

posix_memalign(&buffer, 4096, size);

read(fd, buffer, size);

Direct I/O still uses file system metadata caching.

7. File System Operations

How common operations work internally.

7.1 Creating a File

creat("/home/user/newfile.txt", 0644):

1. Path resolution

- Traverse directories to /home/user

- Each component: lookup in directory, check permissions

2. Allocate inode

- Find free inode in inode bitmap

- Initialize inode (permissions, timestamps, owner)

3. Create directory entry

- Add "newfile.txt" → new inode in parent directory

- Update parent directory mtime

4. Journal transaction (if journaling)

- Log: inode allocation, directory update

- Commit transaction

5. Return file descriptor

- Allocate fd in process fd table

- Point to open file object

Operations: Read parent inode, write parent directory,

write inode bitmap, write new inode

Typically 4+ disk writes (optimized by buffering)

7.2 Writing to a File

write(fd, data, 4096) to middle of file:

1. Find file offset → block mapping

- Consult inode extent tree

- Locate target block

2. Check if block allocated

- Yes: Read-modify-write (if partial block)

- No: Allocate new block

3. Write to page cache

- Find or create cached page

- Copy data to page

- Mark page dirty

4. Update file metadata

- Update mtime

- Update size (if file grew)

- Mark inode dirty

5. Return immediately

- Data in RAM, not yet on disk

- Writeback happens later

For durability: fsync(fd) forces to disk

7.3 Reading a File

read(fd, buffer, 4096):

1. Check page cache

- Hash (inode, offset) → cache lookup

- Hit: Copy to user buffer, done

2. Cache miss: Issue disk read

- Calculate physical block from file offset

- Submit I/O request to block layer

- Process sleeps waiting for completion

3. Read-ahead check

- Was this sequential access?

- Issue async reads for upcoming blocks

4. I/O completion

- Data arrives in page cache

- Copy to user buffer

- Wake up process

5. Return bytes read

- May be less than requested (EOF, etc.)

Cache hot: ~1μs

Cache cold, SSD: ~100μs

Cache cold, HDD: ~10ms

7.4 Deleting a File

unlink("/home/user/file.txt"):

1. Path resolution

- Find parent directory

- Find directory entry for "file.txt"

2. Remove directory entry

- Remove name→inode mapping

- Update parent directory mtime

3. Decrement link count

- inode.nlink -= 1

4. If link count == 0 AND no open file descriptors:

- Deallocate all data blocks (update block bitmap)

- Deallocate inode (update inode bitmap)

- Free space immediately available

5. If link count == 0 BUT file still open:

- Mark inode for deletion

- Actual deletion when last fd closed

- "Deleted but still accessible" state

Note: File contents not actually zeroed!

Just metadata updated.

Data recoverable until overwritten.

8. Special File Systems

Not all file systems store data on disk.

8.1 procfs (/proc)

Virtual file system exposing kernel data:

/proc/

├── 1/ # Process 1 (init)

│ ├── cmdline # Command line

│ ├── environ # Environment variables

│ ├── fd/ # Open file descriptors

│ ├── maps # Memory mappings

│ ├── stat # Process statistics

│ └── ...

├── cpuinfo # CPU information

├── meminfo # Memory statistics

├── filesystems # Supported file systems

├── sys/ # Kernel parameters (sysctl)

│ ├── vm/

│ │ ├── swappiness

│ │ └── dirty_ratio

│ └── kernel/

│ └── hostname

└── ...

Reading /proc/meminfo:

- No disk I/O

- Kernel generates content on read

- Each read fetches fresh data

- File "size" is 0 (content generated dynamically)

8.2 sysfs (/sys)

Structured view of kernel objects:

/sys/

├── block/ # Block devices

│ ├── sda/

│ │ ├── queue/

│ │ │ ├── scheduler

│ │ │ └── read_ahead_kb

│ │ └── stat

│ └── nvme0n1/

├── devices/ # Device hierarchy

│ ├── system/

│ │ └── cpu/

│ │ ├── cpu0/

│ │ └── cpu1/

│ └── pci0000:00/

├── class/ # Device classes

│ ├── net/

│ │ ├── eth0 -> ../../../devices/...

│ │ └── lo

│ └── block/

└── fs/ # File system info

├── ext4/

└── btrfs/

Many files writable for configuration:

echo mq-deadline > /sys/block/sda/queue/scheduler

8.3 tmpfs

RAM-based file system:

mount -t tmpfs -o size=1G tmpfs /mnt/ramdisk

Characteristics:

- Data stored in page cache (RAM)

- Extremely fast (memory speed)

- Lost on reboot (no persistence)

- Can be swapped under memory pressure

Use cases:

- /tmp (temporary files)

- /run (runtime data)

- /dev/shm (POSIX shared memory)

- Build directories (speed up compilation)

Performance:

- Read/write: Memory bandwidth (GB/s)

- No disk I/O whatsoever

- Latency: Nanoseconds

Size limit:

- Prevents one application consuming all RAM

- Default: Half of RAM

- Configurable per mount

8.4 FUSE (Filesystem in Userspace)

User-space file system framework:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Application │

│ open("/mnt/fuse/file") │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ VFS │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FUSE Kernel Module │

│ (forwards to user space) │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────┘

│ /dev/fuse

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ FUSE User Process │

│ (implements file operations) │

│ │

│ Examples: │

│ - sshfs (remote files via SSH) │

│ - s3fs (Amazon S3 as file system) │

│ - encfs (encrypted file system) │

│ - ntfs-3g (NTFS driver) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Overhead: Context switches, but enables flexible FS development

9. Performance Tuning

Optimizing file system performance.

9.1 Mount Options

Performance-relevant mount options:

noatime:

Don't update access time on read

Eliminates write for every read

Highly recommended for most systems

nodiratime:

Don't update access time on directories

Subset of noatime

relatime:

Update atime only if older than mtime

Default in modern Linux

Compromise between noatime and atime

commit=N:

Journal commit interval (seconds)

Higher = fewer syncs, more risk

Lower = safer, more overhead

barrier=0/1:

Write barriers for integrity

Disable only with battery-backed cache

discard:

Issue TRIM commands for deleted blocks

Important for SSD longevity

Can be done periodically (fstrim) instead

9.2 I/O Schedulers

Block layer I/O schedulers:

none (noop):

No reordering, FIFO

Best for NVMe SSDs (no seek time anyway)

Low CPU overhead

mq-deadline:

Deadline guarantee, merge adjacent requests

Good for SSDs and HDDs

Prevents starvation

bfq (Budget Fair Queueing):

Fair scheduling for interactive use

Good for desktop with HDD

Higher CPU overhead

kyber:

Designed for fast SSDs

Low latency focus

Check/set scheduler:

cat /sys/block/sda/queue/scheduler

echo mq-deadline > /sys/block/sda/queue/scheduler

Persistent via udev rules:

ACTION=="add|change", KERNEL=="sd[a-z]", ATTR{queue/scheduler}="mq-deadline"

9.3 File System Choice

Choosing the right file system:

ext4:

- Mature, stable, well-understood

- Good all-around performance

- Best for: General purpose, boot partitions

XFS:

- Excellent for large files

- Scales well with many CPUs

- Best for: Servers, large storage, databases

btrfs:

- Snapshots, compression, checksums

- Flexible storage management

- Best for: Desktop, NAS, when features needed

ZFS:

- Enterprise features, bulletproof

- High memory requirements

- Best for: Data integrity critical, storage servers

F2FS:

- Designed for flash storage

- Log-structured writes

- Best for: SD cards, USB drives, SSDs

Performance comparison (highly workload-dependent):

Sequential writes: XFS ≈ ext4 > btrfs

Random writes: ext4 ≈ XFS > btrfs

Metadata ops: ext4 > XFS ≈ btrfs

9.4 Monitoring and Debugging

# I/O statistics

iostat -x 1

# %util, await, r/s, w/s per device

# Per-process I/O

iotop -o

# Shows processes doing I/O

# File system usage

df -h

# Space usage per mount

# Inode usage

df -i

# Can run out of inodes before space!

# Block layer stats

cat /proc/diskstats

# Detailed file system stats

tune2fs -l /dev/sda1 # ext4

xfs_info /mount/point # XFS

# Trace I/O operations

blktrace -d /dev/sda -o - | blkparse -i -

# File fragmentation

filefrag filename

# Shows extent count and fragmentation

10. Durability and Data Integrity

Ensuring data survives failures.

10.1 The fsync Dance

Ensuring data reaches disk:

write() only puts data in page cache:

write(fd, data, size); // Returns success

// Data may only be in RAM!

For durability, must call fsync:

write(fd, data, size);

fsync(fd); // Waits for disk write

Even fsync isn't always enough:

write(fd, data, size);

fsync(fd);

rename(tmpfile, realfile); // Atomic rename

fsync(directory_fd); // Sync directory too!

fsync vs fdatasync:

fsync: Syncs data AND metadata (mtime, etc.)

fdatasync: Syncs data, metadata only if size changed

Faster when only content changes

10.2 Atomic Operations

Making updates atomic:

Problem: Writing file in place isn't atomic

- Crash during write = partial/corrupt file

- No way to "rollback"

Solution: Write-then-rename pattern

1. Write to temporary file

tmpfile = open("file.tmp", O_CREAT | O_EXCL);

write(tmpfile, data, size);

fsync(tmpfile);

close(tmpfile);

2. Atomic rename

rename("file.tmp", "file"); // Atomic in POSIX

3. Sync directory (for full durability)

dirfd = open(".", O_DIRECTORY);

fsync(dirfd);

Result:

- "file" always contains complete old or new content

- Never partial or corrupt

- rename() is atomic by POSIX guarantee

10.3 Data Integrity Features

Detecting and correcting corruption:

Checksums (btrfs, ZFS):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Every block has checksum │

│ Read: Verify checksum matches data │

│ Mismatch: Silent corruption detected! │

│ With redundancy: Reconstruct from good copy │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Scrubbing:

- Background process reads all data

- Verifies checksums

- Repairs from redundancy if available

- Schedule regularly: btrfs scrub start /mount

DIF/DIX (hardware):

- Data Integrity Field

- Controller-level checksums

- Protects data in flight (cable errors, etc.)

RAID:

- RAID1: Mirror, survives one disk failure

- RAID5/6: Parity, survives 1-2 disk failures

- RAID10: Mirror + stripe, performance + redundancy

10.4 Backup Considerations

File system aware backup:

Snapshot-based backup:

1. Create atomic snapshot (btrfs/ZFS)

2. Backup from snapshot (consistent point-in-time)

3. Delete snapshot after backup

Send/receive (btrfs, ZFS):

btrfs send /mnt/@snapshot | btrfs receive /backup/

zfs send pool/dataset@snap | zfs receive backup/dataset

Incremental:

btrfs send -p @old_snap @new_snap | btrfs receive /backup/

zfs send -i @old @new | zfs receive backup/

Block-level vs file-level:

- Block-level (dd): Copies everything including free space

- File-level (rsync): Skips deleted files, more flexible

- Snapshot-based: Best of both (consistency + efficiency)

Testing restores:

- Untested backup is no backup

- Periodically verify restore process works

- Check restored data integrity

11. Summary and Key Concepts

Consolidating file system knowledge.

11.1 Core Concepts Review

File system fundamentals:

✓ Inodes store metadata, directories map names to inodes

✓ Block allocation maps files to disk blocks

✓ Extents more efficient than individual block pointers

Data integrity:

✓ Journaling ensures crash consistency for metadata

✓ COW file systems inherently crash consistent

✓ Page cache buffers I/O for performance

✓ fsync required for application-level durability

Performance factors:

✓ HDD: Seek time dominates, sequential access crucial

✓ SSD: Random access fast, but write amplification

✓ Page cache: Hot data served from RAM

✓ Read-ahead: Predicts and prefetches sequential data

11.2 Practical Guidelines

For application developers:

1. Call fsync after critical writes

- write() alone doesn't guarantee durability

- Use write-rename pattern for atomic updates

2. Consider direct I/O for large sequential access

- Avoids double-buffering with app cache

- Requires aligned buffers and offsets

3. Understand read-ahead behavior

- Sequential access is heavily optimized

- Random access may benefit from madvise()

4. Handle ENOSPC and disk errors gracefully

- Disk full is recoverable

- I/O errors need careful handling

For system administrators:

1. Choose file system based on workload

- ext4: General purpose

- XFS: Large files, parallel I/O

- btrfs/ZFS: Snapshots, checksums

2. Monitor disk health

- SMART attributes

- File system errors in dmesg

- Regular scrubs for checksumming FS

3. Tune mount options

- noatime for read-heavy workloads

- Appropriate commit interval

- Match I/O scheduler to device type

11.3 Debugging Checklist

When investigating file system issues:

□ Check disk space (df -h) and inode usage (df -i)

□ Review mount options (mount | grep device)

□ Check I/O scheduler (cat /sys/block/dev/queue/scheduler)

□ Monitor I/O patterns (iostat -x, iotop)

□ Look for errors in dmesg/journal

□ Verify file fragmentation (filefrag)

□ Check SMART health (smartctl -a /dev/sda)

□ Test write durability (write, sync, read back)

□ Examine page cache stats (/proc/meminfo)

□ Profile with blktrace for detailed analysis

□ Verify permissions and ownership (ls -la)

□ Check for filesystem corruption (fsck in read-only)

File systems bridge the critical gap between application data needs and the underlying reality of physical storage hardware, transforming raw disk blocks into organized, named, and protected files. From the elegant simplicity of inodes and directories to the sophisticated crash recovery mechanisms of journaling and copy-on-write architectures, these systems embody decades of engineering wisdom accumulated through countless production incidents and research breakthroughs. Understanding file system internals empowers you to make informed choices about storage architecture, debug mysterious performance problems, and ensure your data survives the unexpected. Whether you’re designing database storage engines, optimizing build systems for faster compilation, or simply curious about what happens when you click save, the principles of file system design illuminate one of computing’s most essential and enduring abstractions that touches every aspect of how we work with computers.