Floating Point: How Computers Represent Real Numbers

A deep exploration of IEEE 754 floating point representation, the mathematics behind binary fractions, precision limits, and the subtle bugs that can arise when working with real numbers in code.

Every programmer eventually encounters the classic puzzle: why does 0.1 + 0.2 not equal 0.3? The answer lies in how computers represent real numbers using floating point arithmetic. Understanding IEEE 754 floating point is essential for anyone writing numerical code, financial software, scientific simulations, or graphics applications.

1. The Challenge of Representing Real Numbers

Computers work with finite binary representations, but real numbers are infinite.

1.1 The Fundamental Problem

Integers are straightforward:

42 in binary = 101010

-7 in binary (two's complement, 8-bit) = 11111001

But real numbers have infinite precision:

π = 3.14159265358979323846...

1/3 = 0.33333333... (repeating)

Even simple decimals can be infinite in binary:

0.1 (decimal) = 0.0001100110011... (repeating in binary)

1.2 Why Not Fixed Point?

Fixed point representations dedicate a fixed number of bits to the integer and fractional parts:

Fixed point (16.16 format):

┌────────────────┬────────────────┐

│ Integer part │ Fractional part│

│ (16 bits) │ (16 bits) │

└────────────────┴────────────────┘

Example: 123.456

Integer: 123 = 0000000001111011

Fraction: 0.456 ≈ 0.456 × 65536 = 29884 = 0111010011001100

Problems with fixed point:

- Limited range (max ~32767 with 16.16)

- Fixed precision regardless of magnitude

- 0.000001 and 1000000 need same bits for fraction

1.3 Scientific Notation to the Rescue

Floating point mimics scientific notation:

Scientific notation:

6.022 × 10²³ (Avogadro's number)

1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ (electron charge)

Components:

- Significand (mantissa): 6.022, 1.602

- Base: 10

- Exponent: 23, -19

Binary floating point:

1.01101 × 2⁵ = 101101 (binary) = 45 (decimal)

1.01101 × 2⁻³ = 0.00101101 (binary) = 0.17578125 (decimal)

2. IEEE 754 Format

The IEEE 754 standard defines floating point representation.

2.1 Single Precision (32-bit)

┌───┬──────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────────────┐

│ S │ Exponent │ Mantissa │

│1b │ 8 bits │ 23 bits │

└───┴──────────────────────┴───────────────────────────────────────┘

31 30 23 22 0

S: Sign bit (0 = positive, 1 = negative)

Exponent: Biased by 127 (stored value = actual exponent + 127)

Mantissa: Fractional part (implicit leading 1)

Value = (-1)^S × 1.Mantissa × 2^(Exponent - 127)

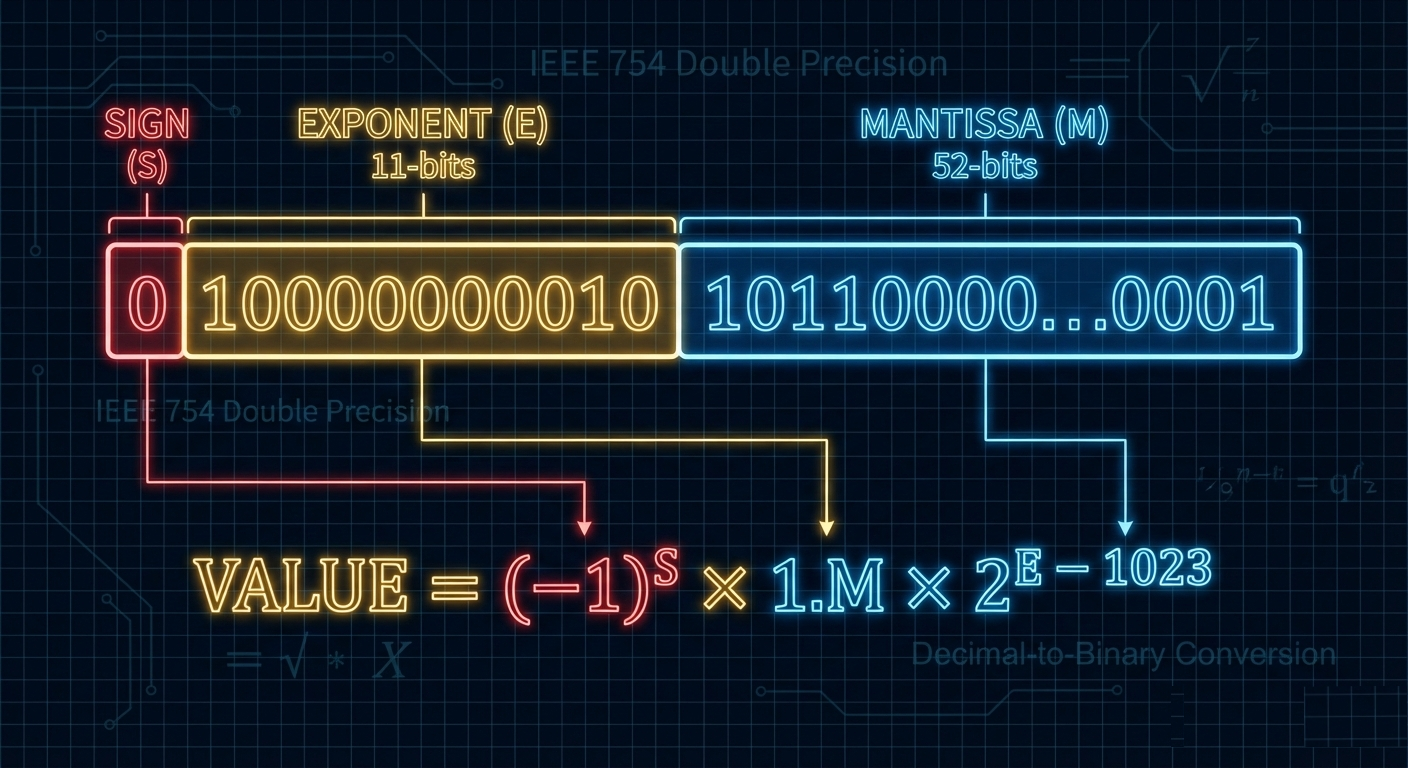

2.2 Double Precision (64-bit)

┌───┬───────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ S │ Exponent │ Mantissa │

│1b │ 11 bits │ 52 bits │

└───┴───────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

63 62 52 51 0

Value = (-1)^S × 1.Mantissa × 2^(Exponent - 1023)

2.3 Encoding Example

Let’s encode -6.75 in single precision:

Step 1: Convert to binary

6.75 = 6 + 0.75

6 = 110 (binary)

0.75 = 0.5 + 0.25 = 0.11 (binary)

6.75 = 110.11 (binary)

Step 2: Normalize

110.11 = 1.1011 × 2²

Step 3: Extract components

Sign: 1 (negative)

Exponent: 2 + 127 = 129 = 10000001

Mantissa: 1011 (drop leading 1, pad with zeros)

10110000000000000000000

Step 4: Combine

1 10000001 10110000000000000000000

Hex: 0xC0D80000

2.4 Decoding Example

Decode 0x40490FDB (single precision):

Binary: 0 10000000 10010010000111111011011

Sign: 0 (positive)

Exponent: 10000000 = 128, actual = 128 - 127 = 1

Mantissa: 1.10010010000111111011011

Value: 1.10010010000111111011011 × 2¹

= 11.0010010000111111011011

= 3 + 0.140625 + ...

≈ 3.14159274...

This is π (to single precision accuracy)!

3. Special Values

IEEE 754 reserves certain bit patterns for special cases.

3.1 Zero

Positive zero: 0 00000000 00000000000000000000000 = +0.0

Negative zero: 1 00000000 00000000000000000000000 = -0.0

+0.0 == -0.0 evaluates to true

But 1.0/+0.0 = +∞ and 1.0/-0.0 = -∞

3.2 Infinity

Positive infinity: 0 11111111 00000000000000000000000 = +∞

Negative infinity: 1 11111111 00000000000000000000000 = -∞

Created by:

- Division by zero: 1.0/0.0 = +∞

- Overflow: 1e38 * 1e38 = +∞

Properties:

- ∞ + 1 = ∞

- ∞ - ∞ = NaN

- ∞ × 0 = NaN

3.3 NaN (Not a Number)

NaN: Exponent all 1s, non-zero mantissa

Examples:

0 11111111 10000000000000000000000 = quiet NaN

0 11111111 00000000000000000000001 = signaling NaN

Created by:

- 0.0/0.0

- ∞ - ∞

- sqrt(-1)

Properties:

- NaN != NaN (NaN is not equal to itself!)

- NaN + anything = NaN

- Any comparison with NaN returns false

3.4 Denormalized Numbers (Subnormals)

Normal numbers: exponent ≠ 0, implicit leading 1

Denormals: exponent = 0, implicit leading 0

Smallest normal (single): 1.0 × 2⁻¹²⁶ ≈ 1.18 × 10⁻³⁸

Smallest denormal (single): 2⁻²³ × 2⁻¹²⁶ = 2⁻¹⁴⁹ ≈ 1.4 × 10⁻⁴⁵

Denormals fill the gap between 0 and smallest normal:

0 denormals smallest normal

│◄──────────────►│◄───────────────

│ gradual │ normal numbers

│ underflow │

4. Precision and Rounding

Understanding the limits of floating point precision.

4.1 Significant Digits

Single precision (23-bit mantissa + implicit 1):

24 bits of precision

≈ 7.22 decimal digits

Double precision (52-bit mantissa + implicit 1):

53 bits of precision

≈ 15.95 decimal digits

Example (single precision):

16777216.0 + 1.0 = 16777216.0 (not 16777217!)

Why? 16777216 = 2²⁴, needs 25 bits to represent 16777217

4.2 The Infamous 0.1 + 0.2 Problem

>>> 0.1 + 0.2

0.30000000000000004

>>> 0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3

False

Why does this happen?

0.1 in binary = 0.0001100110011001100110011... (repeating)

Stored as (double):

0.1 ≈ 0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625

0.2 in binary = 0.001100110011001100110011... (repeating)

Stored as (double):

0.2 ≈ 0.2000000000000000111022302462515654042363166809082031250

Sum:

0.1 + 0.2 ≈ 0.3000000000000000444089209850062616169452667236328125

0.3 stored as:

0.3 ≈ 0.2999999999999999888977697537484345957636833190917968750

The stored representations don't match!

4.3 Rounding Modes

IEEE 754 defines five rounding modes:

1. Round to Nearest, Ties to Even (default)

2.5 → 2, 3.5 → 4, 4.5 → 4, 5.5 → 6

Minimizes cumulative rounding error

2. Round Toward Zero (truncation)

2.9 → 2, -2.9 → -2

3. Round Toward +∞ (ceiling)

2.1 → 3, -2.9 → -2

4. Round Toward -∞ (floor)

2.9 → 2, -2.1 → -3

5. Round to Nearest, Ties Away from Zero

2.5 → 3, -2.5 → -3

4.4 Epsilon and ULP

Machine epsilon (ε): smallest x such that 1.0 + x ≠ 1.0

Single: ε ≈ 1.19 × 10⁻⁷

Double: ε ≈ 2.22 × 10⁻¹⁶

ULP (Unit in Last Place): gap between adjacent floats

At 1.0: ULP = ε

At 2.0: ULP = 2ε

At 1024.0: ULP = 1024ε

The gap between representable numbers grows with magnitude!

5. Common Pitfalls and Bugs

Floating point arithmetic has many subtle traps.

5.1 Equality Comparison

// WRONG: Direct equality comparison

if (result == expected) { ... }

// BETTER: Epsilon comparison

#define EPSILON 1e-9

if (fabs(result - expected) < EPSILON) { ... }

// BEST: Relative epsilon

bool approximately_equal(double a, double b, double rel_epsilon) {

double diff = fabs(a - b);

a = fabs(a);

b = fabs(b);

double largest = (b > a) ? b : a;

return diff <= largest * rel_epsilon;

}

5.2 Catastrophic Cancellation

// Computing b² - 4ac when b ≈ √(4ac)

// Example: a=1, b=10000, c=1

// b² = 100000000

// 4ac = 4

// b² - 4ac = 99999996

// But if b=1000000.0001, c=250000000025.0001

// We lose almost all significant digits!

double discriminant = b*b - 4*a*c; // Catastrophic cancellation

// Better: Reformulate if possible

// Or use higher precision arithmetic

5.3 Accumulation Error

// Summing many small numbers

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < 10000000; i++) {

sum += 0.1f; // Each addition adds error

}

// sum ≈ 999999.9 (not 1000000.0)

// Solution: Kahan summation

float sum = 0.0f;

float c = 0.0f; // Running compensation for lost low-order bits

for (int i = 0; i < 10000000; i++) {

float y = 0.1f - c; // c is zero initially

float t = sum + y; // sum is big, y small, low-order digits lost

c = (t - sum) - y; // (t - sum) recovers high part of y

sum = t; // algebraically, c should be zero

}

// sum ≈ 1000000.0 (much more accurate)

5.4 Order of Operations Matters

// These are NOT equivalent:

double a = (x + y) + z;

double b = x + (y + z);

// Example where order matters:

// x = 1e30, y = -1e30, z = 1.0

// (x + y) + z = 0 + 1 = 1

// x + (y + z) = 1e30 + (-1e30) = 0 (z absorbed)

// Compilers may reorder with -ffast-math!

5.5 Integer to Float Conversion

// Large integers may lose precision

long long big = 9007199254740993LL; // 2^53 + 1

double d = (double)big;

long long back = (long long)d;

// back = 9007199254740992 (lost 1!)

// 2^53 = 9007199254740992 is the last consecutive integer

// representable exactly in double precision

6. Floating Point in Practice

Real-world considerations for numerical code.

6.1 Financial Calculations

// NEVER use float/double for money!

double price = 19.99;

double quantity = 3;

double total = price * quantity;

// total might be 59.96999999999999...

// Use fixed-point decimal types

// Store cents as integers

long price_cents = 1999;

long quantity = 3;

long total_cents = price_cents * quantity; // 5997 cents = $59.97

// Or use decimal libraries

// Python: from decimal import Decimal

// Java: BigDecimal

// C#: decimal type

6.2 Numerical Stability

// Unstable: Variance calculation (one-pass, naive)

double sum = 0, sum_sq = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

sum += x[i];

sum_sq += x[i] * x[i];

}

double variance = (sum_sq - sum*sum/n) / (n-1); // Catastrophic cancellation!

// Stable: Welford's online algorithm

double mean = 0, M2 = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

double delta = x[i] - mean;

mean += delta / (i + 1);

double delta2 = x[i] - mean;

M2 += delta * delta2;

}

double variance = M2 / (n - 1);

6.3 Comparing Floating Point Numbers

// For testing/assertions: relative + absolute tolerance

bool close_enough(double a, double b, double rel_tol, double abs_tol) {

// Handle special cases

if (isnan(a) || isnan(b)) return false;

if (isinf(a) || isinf(b)) return a == b;

double diff = fabs(a - b);

// Absolute tolerance for numbers near zero

if (diff < abs_tol) return true;

// Relative tolerance for larger numbers

double largest = fmax(fabs(a), fabs(b));

return diff <= largest * rel_tol;

}

// Python's math.isclose default:

// rel_tol=1e-9, abs_tol=0.0

6.4 Compiler Flags and Fast Math

# GCC/Clang fast-math flags

-ffast-math # Enables all unsafe optimizations

# Individual flags:

-fno-signed-zeros # Assume +0 = -0

-fno-trapping-math # Assume no FP exceptions

-ffinite-math-only # Assume no inf/nan

-fassociative-math # Allow (a+b)+c = a+(b+c)

-freciprocal-math # Allow x/y = x*(1/y)

# These break IEEE 754 compliance but can be 2-3x faster

# Use only when you understand the implications!

6.5 Hardware Considerations

x87 FPU (legacy):

- 80-bit extended precision internally

- Results depend on precision control register

- Can give different results than SSE

SSE/SSE2:

- Native 32/64-bit operations

- More predictable results

- Default on modern x86-64

ARM NEON:

- May flush denormals to zero by default

- Different rounding behavior possible

Always test numerical code on target hardware!

7. Extended and Alternative Formats

Beyond standard float and double.

7.1 Extended Precision

x87 Extended (80-bit):

Sign: 1 bit

Exponent: 15 bits

Mantissa: 64 bits (explicit leading bit)

Range: ±1.2 × 10⁻⁴⁹³² to ±1.2 × 10⁴⁹³²

Precision: ~19 decimal digits

IEEE 754-2008 Quad (128-bit):

Sign: 1 bit

Exponent: 15 bits

Mantissa: 112 bits

Range: ±6.5 × 10⁻⁴⁹⁶⁶ to ±1.2 × 10⁴⁹³²

Precision: ~34 decimal digits

7.2 Half Precision (16-bit)

IEEE 754 Half (binary16):

┌───┬─────────────┬────────────────────────┐

│ S │ Exponent │ Mantissa │

│1b │ 5 bits │ 10 bits │

└───┴─────────────┴────────────────────────┘

Range: ±6.1 × 10⁻⁵ to ±65504

Precision: ~3.3 decimal digits

Used in:

- Machine learning (bfloat16 variant popular in AI)

- Graphics (color values, HDR)

- Storage (when precision less critical than size)

7.3 bfloat16

Google Brain Float16:

┌───┬─────────────┬────────────────┐

│ S │ Exponent │ Mantissa │

│1b │ 8 bits │ 7 bits │

└───┴─────────────┴────────────────┘

Same exponent range as float32

Truncated mantissa (less precision)

Benefits for ML:

- Fast conversion to/from float32

- Same dynamic range as float32

- Sufficient precision for neural network weights

7.4 Arbitrary Precision Libraries

# Python mpmath

from mpmath import mp, mpf

mp.dps = 50 # 50 decimal places

x = mpf('0.1')

y = mpf('0.2')

z = mpf('0.3')

print(x + y == z) # True!

# GMP (GNU Multiple Precision)

# MPFR (Multiple Precision Floating-Point Reliable)

8. Floating Point Exceptions

IEEE 754 defines five exception conditions.

8.1 Exception Types

1. Invalid Operation

- 0/0, ∞-∞, 0×∞, sqrt(-1)

- Result: NaN

2. Division by Zero

- x/0 where x ≠ 0

- Result: ±∞

3. Overflow

- Result too large to represent

- Result: ±∞ or ±MAX (depending on rounding)

4. Underflow

- Result too small (becomes denormal or zero)

- Result: denormal or 0

5. Inexact

- Result required rounding

- Happens on almost every operation!

8.2 Exception Handling in C

#include <fenv.h>

int main() {

// Clear exception flags

feclearexcept(FE_ALL_EXCEPT);

// Perform operations

double x = 1.0 / 0.0; // Division by zero

double y = sqrt(-1.0); // Invalid

// Check which exceptions occurred

if (fetestexcept(FE_DIVBYZERO)) {

printf("Division by zero occurred\n");

}

if (fetestexcept(FE_INVALID)) {

printf("Invalid operation occurred\n");

}

// Can also trap on exceptions (platform-specific)

return 0;

}

8.3 Debugging with Floating Point Exceptions

// Enable trapping (causes SIGFPE on exception)

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <fenv.h>

void enable_fp_exceptions() {

feenableexcept(FE_INVALID | FE_DIVBYZERO | FE_OVERFLOW);

}

// Now invalid operations crash immediately

// Much easier to find the source of NaN!

9. Testing Floating Point Code

Strategies for verifying numerical correctness.

9.1 Unit Testing Approaches

import math

import unittest

class TestNumerics(unittest.TestCase):

def test_close_values(self):

result = compute_something()

expected = 3.14159

# assertAlmostEqual uses places (decimal places)

self.assertAlmostEqual(result, expected, places=5)

# Or use math.isclose for relative tolerance

self.assertTrue(math.isclose(result, expected, rel_tol=1e-6))

def test_special_values(self):

self.assertTrue(math.isnan(0.0 / 0.0))

self.assertTrue(math.isinf(1.0 / 0.0))

def test_edge_cases(self):

# Test near overflow

# Test near underflow

# Test with denormals

# Test with very large/small inputs

pass

9.2 Property-Based Testing

from hypothesis import given, strategies as st

@given(st.floats(allow_nan=False, allow_infinity=False))

def test_square_root_property(x):

if x >= 0:

result = math.sqrt(x)

# sqrt(x)^2 should be close to x

assert math.isclose(result * result, x, rel_tol=1e-10)

9.3 Reference Implementations

// Compare against arbitrary precision library

#include <mpfr.h>

void verify_accuracy() {

mpfr_t x, expected;

mpfr_init2(x, 256); // 256 bits precision

mpfr_init2(expected, 256);

// Compute in high precision

mpfr_set_d(x, 0.1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_sin(expected, x, MPFR_RNDN);

// Compare with standard library

double std_result = sin(0.1);

double mpfr_result = mpfr_get_d(expected, MPFR_RNDN);

double error = fabs(std_result - mpfr_result);

assert(error < 1e-15); // Within expected precision

mpfr_clear(x);

mpfr_clear(expected);

}

10. Performance Optimization

Making floating point code fast.

10.1 SIMD Vectorization

// Scalar loop

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

// Vectorized (AVX2, 8 floats at once)

#include <immintrin.h>

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 8) {

__m256 va = _mm256_load_ps(&a[i]);

__m256 vb = _mm256_load_ps(&b[i]);

__m256 vc = _mm256_add_ps(va, vb);

_mm256_store_ps(&c[i], vc);

}

10.2 Avoiding Denormals

// Denormal operations can be 10-100x slower!

// Solution 1: Flush denormals to zero (DAZ + FTZ)

#include <immintrin.h>

_mm_setcsr(_mm_getcsr() | 0x8040);

// Solution 2: Add small constant to avoid denormals

#define SMALL_CONSTANT 1e-30f

float safe_divide(float a, float b) {

return a / (b + SMALL_CONSTANT);

}

10.3 Division is Expensive

// Division is ~10-20x slower than multiplication

// SLOW: Multiple divisions by same value

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = data[i] / scale; // Division each iteration

}

// FAST: Compute reciprocal once

float inv_scale = 1.0f / scale;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = data[i] * inv_scale; // Multiplication each iteration

}

10.4 Fast Approximations

// Fast inverse square root (Quake III)

// Famous but now mostly obsolete (rsqrtss is faster)

float q_rsqrt(float number) {

long i;

float x2, y;

const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

x2 = number * 0.5F;

y = number;

i = *(long *)&y;

i = 0x5f3759df - (i >> 1); // Magic constant!

y = *(float *)&i;

y = y * (threehalfs - (x2 * y * y)); // Newton-Raphson

return y;

}

// Modern: Use hardware RSQRT with Newton-Raphson refinement

#include <immintrin.h>

float fast_rsqrt(float x) {

__m128 v = _mm_set_ss(x);

v = _mm_rsqrt_ss(v); // Hardware approximation

// Optional: Newton-Raphson for more precision

return _mm_cvtss_f32(v);

}

11. Language-Specific Considerations

Different languages handle floating point differently.

11.1 Python

# Python float is always 64-bit double

import sys

print(sys.float_info)

# Decimal for exact decimal arithmetic

from decimal import Decimal, getcontext

getcontext().prec = 50 # 50 significant digits

d = Decimal('0.1') + Decimal('0.2')

print(d == Decimal('0.3')) # True!

# Fractions for exact rational arithmetic

from fractions import Fraction

f = Fraction(1, 10) + Fraction(2, 10)

print(f == Fraction(3, 10)) # True!

11.2 JavaScript

// JavaScript only has 64-bit doubles (Number)

console.log(0.1 + 0.2); // 0.30000000000000004

// BigInt for exact large integers (but no decimals)

const big = 9007199254740993n; // Beyond safe integer

// For exact decimals, use libraries like decimal.js

11.3 Java

// StrictMath for reproducible results

double a = StrictMath.sin(0.5);

// BigDecimal for exact decimal arithmetic

import java.math.BigDecimal;

BigDecimal d = new BigDecimal("0.1")

.add(new BigDecimal("0.2"));

System.out.println(d.equals(new BigDecimal("0.3"))); // true

// strictfp keyword for reproducible floating point

strictfp class ReproducibleMath {

double compute(double x) {

return Math.sin(x) * Math.cos(x);

}

}

11.4 Rust

// Rust has f32 and f64, follows IEEE 754

let x: f64 = 0.1 + 0.2;

println!("{}", x); // 0.30000000000000004

// Explicit handling of special values

if x.is_nan() { /* handle */ }

if x.is_infinite() { /* handle */ }

// Total ordering for floats (including NaN)

use std::cmp::Ordering;

fn total_cmp(a: f64, b: f64) -> Ordering {

a.total_cmp(&b)

}

12. Real-World Floating Point Stories

Historical incidents and lessons learned from floating point bugs.

12.1 The Patriot Missile Failure (1991)

During the Gulf War, a Patriot missile battery failed to intercept

a Scud missile, resulting in 28 deaths.

Root cause: Time accumulated in 0.1 second increments

- 0.1 cannot be represented exactly in binary

- Error: ~0.000000095 seconds per tick

- After 100 hours: 0.34 second drift

- Scud traveling at Mach 5: 500+ meter targeting error

The fix: Periodic system restart (not implemented)

Lesson: Tiny errors accumulate over time

12.2 The Vancouver Stock Exchange Index (1982)

The Vancouver Stock Exchange started a new index at 1000.000.

After 22 months, the index had fallen to ~520.

Problem: Should have been around ~1098.

Root cause: Truncation instead of rounding

- Index recalculated thousands of times daily

- Each calculation truncated to 3 decimal places

- Each truncation lost a tiny amount of value

- Cumulative loss: nearly half the index value!

The fix: Proper rounding, recalculation from scratch

12.3 The Ariane 5 Explosion (1996)

The Ariane 5 rocket exploded 37 seconds after launch.

Cost: $370 million cargo lost.

Root cause: Float-to-integer conversion overflow

- Horizontal velocity stored as 64-bit float

- Converted to 16-bit signed integer

- Ariane 5 was faster than Ariane 4

- Velocity exceeded 32767 (16-bit max)

- Exception handler shut down navigation

- Rocket veered off course, self-destructed

Lesson: Always check range before conversion

12.4 Excel 2007 Bug

Excel 2007 displayed certain calculation results incorrectly.

850 × 77.1 = 65535 (should be 65534.99999...)

Root cause: Special case in display formatting

- Results very close to 65536 or 65535

- Formatting code had incorrect boundary check

- Binary representation was correct

- Only display was wrong

Lesson: Floating point bugs can hide in unexpected places

12.5 Games and Physics Engines

Common floating point issues in games:

1. Coordinate precision at world edges

- Player at (1000000, 1000000) has less precision

- Objects jitter or behave erratically

- Solution: Floating origin (re-center world)

2. Deterministic multiplayer

- Different CPUs give different results

- x87 vs SSE, compiler flags matter

- Solution: Fixed point, or strict FP settings

3. Physics tunneling

- Fast objects pass through walls

- Position update exceeds collision bounds

- Solution: Continuous collision detection

13. Interval Arithmetic and Error Bounds

Tracking and bounding floating point error.

13.1 Interval Arithmetic Basics

// Instead of a single value, track [lower, upper] bounds

typedef struct {

double lo; // Lower bound

double hi; // Upper bound

} Interval;

Interval interval_add(Interval a, Interval b) {

// Set rounding modes for guaranteed bounds

Interval result;

fesetround(FE_DOWNWARD);

result.lo = a.lo + b.lo;

fesetround(FE_UPWARD);

result.hi = a.hi + b.hi;

return result;

}

// After computation, interval width shows error bounds

double width(Interval i) {

return i.hi - i.lo;

}

13.2 Applications of Interval Arithmetic

Validated numerics:

- Prove results are correct within bounds

- Detect when computation is unstable

- Used in formal verification

Computer graphics:

- Ray-box intersection with guaranteed correctness

- Robust geometric predicates

Scientific computing:

- Verified solutions to differential equations

- Trusted optimization results

13.3 Error Analysis Example

// Analyzing error in polynomial evaluation

// f(x) = x³ - 3x + 2 at x = 1.0000001

// Direct evaluation (Horner's method)

double horner(double x) {

return ((x) * x - 3) * x + 2; // 3 ops

}

// Error analysis:

// Each operation introduces error ≤ 0.5 ULP

// Errors can compound or cancel

// Result error: typically a few ULPs

// For critical code: use compensated algorithms

// or interval arithmetic for guaranteed bounds

14. Floating Point in Databases and Distributed Systems

Special considerations for data storage and transmission.

14.1 Database Storage

-- Different databases handle floats differently

-- PostgreSQL: real (32-bit), double precision (64-bit)

-- Exact comparison unreliable

SELECT * FROM t WHERE price = 19.99; -- Risky!

SELECT * FROM t WHERE ABS(price - 19.99) < 0.001; -- Better

-- For money: Use DECIMAL/NUMERIC

CREATE TABLE products (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

price DECIMAL(10, 2) -- 10 digits, 2 after decimal

);

14.2 Serialization Challenges

// Binary serialization: preserve exact bits

void serialize_double(double d, uint8_t *buf) {

memcpy(buf, &d, sizeof(double));

}

// Text serialization: can lose precision!

printf("%.15g", d); // May not round-trip exactly

// Round-trip guarantee requires enough digits

// Double: 17 significant digits for round-trip

printf("%.17g", d); // Guaranteed round-trip

// Or use hexadecimal float format

printf("%a", d); // Example: 0x1.921fb54442d18p+1

14.3 Distributed Computation

Challenges in distributed floating point:

1. Different hardware architectures

- x86 vs ARM may give slightly different results

- GPU vs CPU differences

2. Non-deterministic reduction

- Parallel sum depends on order

- Results vary between runs

3. Solutions:

- Require specific rounding mode

- Use reproducible reduction algorithms

- Define tolerance for result matching

- Use fixed-point for critical calculations

14.4 Cross-Platform Reproducibility

// Achieving reproducible results across platforms

// 1. Use strict floating point

#pragma STDC FENV_ACCESS ON

// 2. Avoid excess precision

// Compile with: -ffp-contract=off

// Or explicitly round intermediate results

float temp = (float)(a * b); // Force single precision

// 3. Specify rounding mode

fesetround(FE_TONEAREST);

// 4. Handle denormals consistently

// Either flush to zero everywhere, or preserve everywhere

// 5. Be careful with transcendental functions

// sin(), exp(), etc. may differ between platforms

// Consider Taylor series or lookup tables for consistency

15. Advanced Topics

Cutting-edge developments in floating point.

15.1 Posit Numbers

An alternative to IEEE 754 floats:

Posit format:

┌───┬────────────┬──────────┬───────────┐

│ S │ Regime │ Exponent │ Fraction │

│1b │ variable │ variable │ variable │

└───┴────────────┴──────────┴───────────┘

Key differences:

- Tapered precision (more bits near 1.0)

- No NaN or ±∞ (controversial)

- Simpler exception handling

- Claimed better accuracy for many tasks

Status: Research, not widely adopted yet

15.2 Stochastic Rounding

Traditional: Round to nearest (deterministic)

Stochastic: Probabilistically round up or down

Example: 2.3 rounded stochastically

- 70% chance → 2

- 30% chance → 3

- Expected value = 2.3 (unbiased!)

Benefits for machine learning:

- Prevents systematic rounding bias

- Better gradient flow in training

- Enables lower precision without accuracy loss

15.3 Mixed Precision Computing

Strategy: Use different precisions for different purposes

Example in deep learning:

1. Store weights in FP32

2. Compute forward pass in FP16/BF16

3. Accumulate in FP32

4. Update weights in FP32

Benefits:

- 2x memory savings

- 2-8x compute speedup (tensor cores)

- Minimal accuracy loss

Requires careful loss scaling to prevent underflow

15.4 Unum and Type III Unums

Universal Numbers (Unums):

- Variable-size representation

- Exact arithmetic when possible

- Track uncertainty explicitly

Type III Unums (Posits + Valids):

- Posits for individual values

- Valids for interval bounds

- Goal: Replace IEEE 754

Current status: Academic research

Adoption barriers: Hardware support, ecosystem

16. Practical Guidelines by Domain

Different applications have different floating point needs.

16.1 Scientific Computing

Requirements:

- Maximum precision for simulation accuracy

- Error propagation awareness

- Reproducibility for verification

Recommendations:

✓ Use double precision by default

✓ Consider quad precision for ill-conditioned problems

✓ Implement error estimation

✓ Use stable algorithms (pivoting, Kahan summation)

✓ Verify against analytical solutions when available

✓ Document numerical assumptions and limitations

16.2 Financial Applications

Requirements:

- Exact decimal arithmetic for regulations

- No rounding surprises

- Audit trail accuracy

Recommendations:

✓ NEVER use float/double for money

✓ Use decimal types (BigDecimal, Decimal, NUMERIC)

✓ Define rounding rules explicitly

✓ Store as integers (cents, basis points)

✓ Test with boundary values and regulatory scenarios

✓ Document rounding policy in specifications

16.3 Machine Learning and AI

Requirements:

- Throughput over precision

- Memory efficiency for large models

- GPU/accelerator compatibility

Recommendations:

✓ Use FP16/BF16 for inference when possible

✓ Mixed precision training (FP16 compute, FP32 accum)

✓ Monitor for overflow/underflow during training

✓ Use loss scaling for gradient underflow prevention

✓ Quantization-aware training for INT8 deployment

✓ Test model accuracy across precision levels

16.4 Graphics and Games

Requirements:

- Fast performance for real-time rendering

- Visual correctness (not numerical)

- Large world coordinate handling

Recommendations:

✓ Float32 for most calculations

✓ Floating origin for open worlds

✓ Double precision for physics simulation core

✓ Robust geometric predicates for collision

✓ Fast approximations where visual error is acceptable

✓ Test at extreme coordinates and time values

16.5 Embedded Systems

Requirements:

- Limited hardware resources

- Deterministic timing

- Power efficiency

Recommendations:

✓ Consider fixed-point arithmetic

✓ Use software float emulation if no FPU

✓ Profile floating point instruction costs

✓ Avoid denormals (flush to zero)

✓ Minimize divisions (precompute reciprocals)

✓ Consider CORDIC algorithms for trig functions

16.6 Web and JavaScript Applications

Requirements:

- Cross-browser consistency

- Only 64-bit doubles available (in Number)

- Interoperability with JSON

Recommendations:

✓ Use BigInt for large exact integers

✓ Decimal.js or similar for precise decimals

✓ Be aware of JSON number limitations

✓ Validate numeric ranges from user input

✓ Use explicit rounding for display

✓ Test across browsers and platforms

17. Debugging Floating Point Issues

Systematic approaches to finding and fixing floating point bugs.

17.1 Diagnostic Techniques

// Print exact representation

#include <stdio.h>

void print_float_bits(float f) {

unsigned int bits;

memcpy(&bits, &f, sizeof(bits));

printf("Value: %g\n", f);

printf("Hex: 0x%08X\n", bits);

printf("Sign: %d\n", (bits >> 31) & 1);

printf("Exp: %d (biased %d)\n",

((bits >> 23) & 0xFF) - 127,

(bits >> 23) & 0xFF);

printf("Mantissa: 0x%06X\n", bits & 0x7FFFFF);

}

// Hex float format in C99

printf("%a\n", 0.1); // Prints: 0x1.999999999999ap-4

17.2 Common Symptoms and Causes

Symptom: Result is NaN

Causes:

├─ 0/0, ∞-∞, 0×∞

├─ sqrt of negative number

├─ Uninitialized floating point variable

└─ Error propagated from earlier computation

Symptom: Result is unexpectedly zero

Causes:

├─ Underflow (value too small)

├─ Catastrophic cancellation

└─ Denormal flushing

Symptom: Results differ between debug/release

Causes:

├─ Different optimization levels

├─ x87 vs SSE codegen

├─ Fast-math flags enabled in release

└─ Uninitialized memory (different in debug)

Symptom: Results differ between machines

Causes:

├─ Different CPU architectures

├─ Different compiler versions

├─ Different math library implementations

└─ Different SIMD instruction sets

17.3 Floating Point Sanitizers

# GCC/Clang undefined behavior sanitizer catches some FP issues

clang -fsanitize=undefined,float-divide-by-zero program.c

# Enable FP exceptions to catch issues early

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <fenv.h>

feenableexcept(FE_INVALID | FE_OVERFLOW | FE_DIVBYZERO);

// Now bad operations cause SIGFPE

# Valgrind can detect some issues

valgrind --tool=memcheck ./program

17.4 Systematic Testing Strategy

1. Boundary values

├─ Zero (positive and negative)

├─ Smallest positive normal and denormal

├─ Largest finite value

├─ Infinity and NaN

└─ Powers of 2 (exactly representable)

2. Special cases

├─ Values that can't be represented exactly (0.1, 0.2)

├─ Values near overflow threshold

├─ Values near underflow threshold

└─ Values that cause cancellation

3. Randomized testing

├─ Property-based testing (Hypothesis, QuickCheck)

├─ Comparison with arbitrary precision library

└─ Cross-platform result comparison

4. Stress testing

├─ Many iterations of accumulation

├─ Deep recursion with floating point

└─ Extreme input ranges

18. Summary

Floating point representation is a fundamental compromise between range, precision, and performance:

IEEE 754 format:

- Sign bit, biased exponent, implicit-leading-1 mantissa

- Single (32-bit): ~7 decimal digits

- Double (64-bit): ~16 decimal digits

Special values:

- Zero (positive and negative)

- Infinity (positive and negative)

- NaN (not equal to itself)

- Denormals (gradual underflow)

Common pitfalls:

- Never compare floats with

== - 0.1 cannot be represented exactly

- Order of operations affects results

- Large magnitude differences cause precision loss

Best practices:

- Use double unless you have good reason not to

- Never use float/double for money

- Use epsilon comparisons with relative tolerance

- Consider Kahan summation for accuracy

- Test edge cases and special values

- Understand your compiler’s optimization flags

Understanding floating point is essential for writing correct numerical code. The abstractions are leaky, the edge cases are numerous, and the bugs are subtle. But with knowledge of how floating point works internally, you can anticipate problems and write robust numerical software.