Lock-Free Data Structures: Concurrency Without the Wait

Explore how lock-free algorithms achieve thread-safe data access without traditional locks. Learn the theory behind compare-and-swap, the ABA problem, memory ordering, and practical implementations that power high-performance systems.

Traditional locks have served concurrent programming for decades, but they come with costs: contention, priority inversion, and the ever-present risk of deadlock. Lock-free data structures offer an alternative—algorithms that guarantee system-wide progress even when individual threads stall. This post explores the theory, challenges, and practical implementations of lock-free programming.

1. Why Lock-Free?

Consider a simple counter shared among threads. With a mutex:

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

counter++;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

This works, but has problems:

- Contention: Threads block waiting for the lock, wasting CPU cycles

- Priority inversion: A high-priority thread waits for a low-priority thread holding the lock

- Deadlock risk: Multiple locks acquired in different orders can deadlock

- Fault tolerance: If a thread holding a lock crashes, the system may hang

Lock-free algorithms address these issues by ensuring that at least one thread always makes progress, regardless of what other threads do—including if they’re suspended, killed, or running slowly.

1.1 Progress Guarantees

Concurrent algorithms are classified by their progress guarantees:

Blocking (lock-based): A thread can be prevented from making progress indefinitely by other threads. If a thread holding a lock is suspended, all waiters block.

Obstruction-free: A thread makes progress if it runs in isolation (no other threads are active). The weakest non-blocking guarantee.

Lock-free: At least one thread makes progress in a finite number of steps, regardless of what other threads do. Individual threads might starve, but the system never deadlocks.

Wait-free: Every thread makes progress in a bounded number of steps. The strongest guarantee—no thread ever starves.

Most practical “lock-free” implementations are technically lock-free (not wait-free), as wait-free algorithms are often complex and slower.

1.2 The Performance Argument

Lock-free isn’t always faster than lock-based code:

- Under low contention, locks are fast (uncontended lock acquisition is ~25 nanoseconds on modern CPUs)

- Lock-free operations involve expensive atomic instructions and memory barriers

- Lock-free algorithms are harder to reason about and optimize

Lock-free shines when:

- Contention is high (many threads competing for access)

- Latency variance matters (locks cause unpredictable wait times)

- Fault isolation is critical (a stalled thread shouldn’t block others)

- Real-time constraints exist (bounded progress is required)

2. The Building Block: Compare-and-Swap

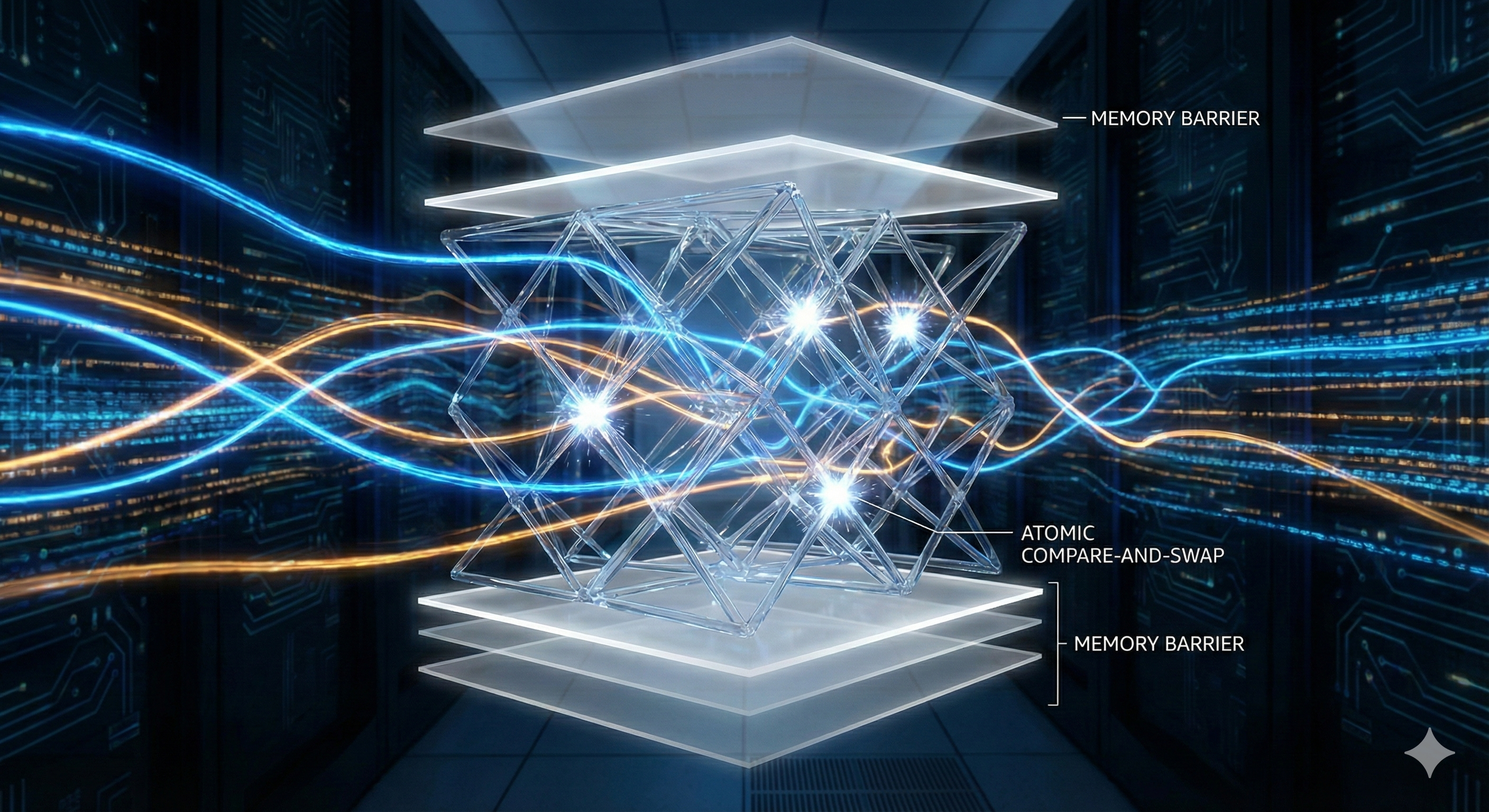

Lock-free algorithms are built on atomic hardware primitives. The most important is Compare-and-Swap (CAS):

bool CAS(int* addr, int expected, int new_value) {

// Atomically:

if (*addr == expected) {

*addr = new_value;

return true;

}

return false;

}

CAS reads the value at an address, compares it to an expected value, and if they match, writes a new value—all atomically. If the comparison fails, the operation fails, and the caller typically retries.

2.1 Hardware Support

Modern CPUs provide CAS as a single instruction:

- x86/x64:

CMPXCHG(compare and exchange) - ARM:

LDXR/STXR(load-exclusive/store-exclusive) - RISC-V:

LR/SC(load-reserved/store-conditional)

These instructions coordinate with the cache coherence protocol to ensure atomicity across cores.

2.2 CAS-Based Counter

Here’s a lock-free counter using CAS:

void increment(atomic_int* counter) {

int old_val, new_val;

do {

old_val = atomic_load(counter);

new_val = old_val + 1;

} while (!atomic_compare_exchange_weak(counter, &old_val, new_val));

}

The loop retries if another thread modified the counter between the load and the CAS. This “read-modify-write” pattern is fundamental to lock-free programming.

2.3 Other Atomic Primitives

Beyond CAS, useful atomics include:

- Fetch-and-add (FAA): Atomically increment and return the old value. Faster than CAS for counters.

- Fetch-and-or/and: Atomically set/clear bits.

- Exchange: Atomically swap values.

- Load-link/Store-conditional (LL/SC): More flexible than CAS on some architectures; detects any intervening write.

Modern languages expose these through std::atomic (C++), java.util.concurrent.atomic (Java), sync/atomic (Go), and Atomic* types (Rust).

3. Memory Ordering: The Hidden Complexity

CAS guarantees atomicity of a single operation, but programs execute multiple operations. Without additional constraints, the CPU and compiler may reorder operations, breaking algorithms.

3.1 The Problem

Consider a flag-based synchronization:

// Thread 1

data = 42;

ready = true;

// Thread 2

while (!ready);

print(data); // Might print garbage, not 42!

Even without compiler optimizations, CPUs may reorder stores. Thread 2 might see ready = true before data = 42 is visible.

3.2 Memory Ordering Options

Memory orderings specify how operations are ordered relative to each other:

Relaxed (memory_order_relaxed): No ordering guarantees. Only atomicity is ensured. Fast but dangerous.

Acquire (memory_order_acquire): No reads or writes in the current thread can be reordered before this load. Used when “acquiring” access to shared data.

Release (memory_order_release): No reads or writes in the current thread can be reordered after this store. Used when “releasing” data for others to see.

Acquire-release (memory_order_acq_rel): Combines acquire and release. Used for read-modify-write operations.

Sequential consistency (memory_order_seq_cst): The strongest ordering. All seq_cst operations appear to execute in a single total order. Simplest to reason about but slowest.

3.3 Correct Synchronization

The flag example, fixed:

// Thread 1

data = 42;

atomic_store_explicit(&ready, true, memory_order_release);

// Thread 2

while (!atomic_load_explicit(&ready, memory_order_acquire));

print(data); // Guaranteed to print 42

The release-acquire pair establishes a “happens-before” relationship: Thread 1’s writes before the release are visible to Thread 2’s reads after the acquire.

3.4 Fences

Memory fences (barriers) provide ordering without associated data:

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_release); // All prior writes complete

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_acquire); // All subsequent reads see prior writes

Fences are a blunt instrument—they order all operations, not just specific ones. Prefer atomic operations with appropriate orderings when possible.

4. The ABA Problem

CAS checks if a value is the same as expected, but “the same” isn’t always good enough.

4.1 The Problem Illustrated

Consider a lock-free stack using CAS to update the top pointer:

// Pop operation

Node* pop() {

Node* old_top;

do {

old_top = top;

if (old_top == NULL) return NULL;

} while (!CAS(&top, old_top, old_top->next));

return old_top;

}

Now imagine:

- Thread 1 reads

top = A, prepares to CAS toA->next(B) - Thread 1 is suspended

- Thread 2 pops A, pops B, pushes C, pushes A back (same address, reused!)

- Thread 1 resumes, CAS succeeds (top is A), sets

top = B - But B was already popped! Stack is corrupted.

Thread 1’s CAS succeeded because top was A before and after—but the stack’s structure changed in between.

4.2 Solutions

Version counters / tagged pointers:

Pack a version counter with the pointer. Increment the counter on every modification:

struct TaggedPointer {

Node* ptr;

uint64_t tag;

};

CAS on the entire 128-bit structure (using CMPXCHG16B on x64). The tag changes even if the pointer value repeats.

Hazard pointers:

Each thread publishes the pointers it’s currently using. Memory is only reclaimed when no thread has it as a hazard pointer. Prevents reuse of actively-accessed memory.

Epoch-based reclamation (EBR):

Divide time into epochs. Memory freed in epoch N can only be reused after all threads have passed through epoch N+1. Lighter weight than hazard pointers.

Reference counting:

Maintain a reference count with the pointer. Memory is freed only when the count reaches zero. Requires atomic double-width operations or split reference counts.

5. Lock-Free Stack

Let’s build a complete lock-free stack with proper memory reclamation using hazard pointers.

5.1 Basic Structure

struct Node {

int data;

Node* next;

};

struct LockFreeStack {

atomic<Node*> top;

};

5.2 Push Operation

void push(LockFreeStack* stack, int value) {

Node* new_node = new Node{value, nullptr};

Node* old_top;

do {

old_top = stack->top.load(memory_order_relaxed);

new_node->next = old_top;

} while (!stack->top.compare_exchange_weak(

old_top, new_node,

memory_order_release, // Success: release new node

memory_order_relaxed // Failure: no ordering needed

));

}

The release ordering ensures the new node’s initialization is visible before it becomes reachable via top.

5.3 Pop Operation with Hazard Pointers

Node* pop(LockFreeStack* stack, HazardPointer* hp) {

Node* old_top;

do {

old_top = stack->top.load(memory_order_acquire);

if (old_top == nullptr) return nullptr;

// Protect this pointer from reclamation

hp->set(old_top);

// Re-check after publishing hazard pointer

if (stack->top.load(memory_order_acquire) != old_top) {

continue; // Pointer changed, retry

}

} while (!stack->top.compare_exchange_weak(

old_top, old_top->next,

memory_order_relaxed,

memory_order_relaxed

));

hp->clear();

// Defer deletion: retire(old_top)

return old_top;

}

The hazard pointer ensures old_top isn’t freed while we’re accessing old_top->next. The re-check after setting the hazard pointer handles the race where the node is freed between our load and our hazard pointer publication.

5.4 Memory Reclamation

Hazard pointer memory management:

void retire(Node* node) {

// Add to thread-local retired list

retired_list.push(node);

// Periodically scan and free safe nodes

if (retired_list.size() > threshold) {

scan_and_free();

}

}

void scan_and_free() {

// Collect all active hazard pointers

set<Node*> hazards = collect_all_hazard_pointers();

// Free nodes not in hazard set

for (Node* node : retired_list) {

if (hazards.find(node) == hazards.end()) {

delete node;

} else {

still_retired.push(node); // Keep for later

}

}

retired_list = still_retired;

}

6. Lock-Free Queue

Queues are trickier than stacks because they have two ends (head and tail) that can be modified concurrently.

6.1 Michael-Scott Queue

The classic lock-free queue by Michael and Scott (1996):

struct Node {

int data;

atomic<Node*> next;

};

struct MSQueue {

atomic<Node*> head;

atomic<Node*> tail;

};

Key insight: use a “dummy” node so the queue is never truly empty (head and tail always point to something).

6.2 Enqueue Operation

void enqueue(MSQueue* q, int value) {

Node* new_node = new Node{value, nullptr};

while (true) {

Node* tail = q->tail.load(memory_order_acquire);

Node* next = tail->next.load(memory_order_acquire);

// Check tail hasn't moved

if (tail != q->tail.load(memory_order_acquire)) continue;

if (next == nullptr) {

// tail->next is null, try to link new node

if (tail->next.compare_exchange_weak(

next, new_node, memory_order_release)) {

// Success! Try to advance tail (optional)

q->tail.compare_exchange_strong(

tail, new_node, memory_order_release);

return;

}

} else {

// tail->next is not null, tail is lagging

// Help advance tail

q->tail.compare_exchange_weak(

tail, next, memory_order_release);

}

}

}

The “help advance tail” step is crucial: even if one thread stalls after linking a node but before updating tail, other threads will move tail forward.

6.3 Dequeue Operation

int dequeue(MSQueue* q, int* result) {

while (true) {

Node* head = q->head.load(memory_order_acquire);

Node* tail = q->tail.load(memory_order_acquire);

Node* next = head->next.load(memory_order_acquire);

// Check head hasn't moved

if (head != q->head.load(memory_order_acquire)) continue;

if (head == tail) {

// Queue empty or tail lagging

if (next == nullptr) {

return false; // Queue is empty

}

// Tail lagging, help advance it

q->tail.compare_exchange_weak(

tail, next, memory_order_release);

} else {

// Read data before CAS (might lose the node after CAS)

*result = next->data;

if (q->head.compare_exchange_weak(

head, next, memory_order_release)) {

// Successfully dequeued, retire old head (dummy)

retire(head);

return true;

}

}

}

}

6.4 Analysis

The Michael-Scott queue is elegant but has performance issues:

- Cache line bouncing: Head and tail are on different cache lines, but high contention still causes coherence traffic

- Memory reclamation: Requires hazard pointers or similar; adds overhead

- FIFO guarantee: True FIFO even under contention, but at the cost of serialization

Modern variations address these issues with techniques like combining (batch operations) and elimination (concurrent push/pop cancel out).

7. Lock-Free Hash Map

Hash maps combine multiple lock-free challenges: dynamic resizing, multiple buckets, and linked structure management.

7.1 Split-Ordered Lists

The split-ordered list (Shalev and Shavit, 2006) provides a lock-free hash map with dynamic resizing:

- Items are stored in a single lock-free linked list, sorted by a “split-order” key

- The hash table is an array of pointers into this list

- Resizing only adds new pointers; no items move

The split-order key is derived from the hash by bit-reversal, ensuring that when a bucket splits, items naturally divide between the new buckets based on their position in the list.

7.2 Simplified Lock-Free Hash Map

A simpler approach uses per-bucket lock-free lists:

struct HashMap {

atomic<Node*>* buckets;

size_t num_buckets;

};

Node* find(HashMap* map, int key) {

size_t bucket = hash(key) % map->num_buckets;

Node* curr = map->buckets[bucket].load(memory_order_acquire);

while (curr != nullptr) {

if (curr->key == key) return curr;

curr = curr->next.load(memory_order_acquire);

}

return nullptr;

}

Insert and delete follow the lock-free list pattern, operating on a single bucket.

7.3 Concurrent Resizing

Resizing a lock-free hash map is complex:

- Allocate new bucket array

- Redirect lookups to check both old and new arrays

- Gradually migrate items from old to new buckets

- Once migration complete, free old array

Each step requires careful synchronization. Some implementations simply use a read-write lock for resizing (hybrid approach), accepting brief blocking during the infrequent resize operation.

8. Read-Copy-Update (RCU)

RCU is a synchronization mechanism optimized for read-heavy workloads. It’s widely used in the Linux kernel.

8.1 The Concept

RCU splits updates into phases:

- Copy: Create a new version of the data structure

- Update: Atomically swing a pointer to the new version

- Wait: Wait until no reader can have a reference to the old version

- Reclaim: Free the old version

Readers access data without any synchronization—they simply read the pointer and follow it. Writers bear all the synchronization cost.

8.2 Grace Periods

The key innovation is the “grace period” concept. A grace period is a time interval after which all pre-existing readers have completed. RCU ensures:

- Readers are in well-defined “RCU read-side critical sections”

- A grace period elapses when every CPU has passed through a quiescent state (context switch, idle, user mode)

- After a grace period, old data can be safely freed

8.3 API Example

// Reader

rcu_read_lock();

Node* node = rcu_dereference(global_ptr); // Safe access

int val = node->data;

rcu_read_unlock();

// Writer

Node* new_node = kmalloc(...); // Allocate new

new_node->data = new_value;

old = rcu_assign_pointer(global_ptr, new_node); // Publish

synchronize_rcu(); // Wait for grace period

kfree(old); // Now safe to free

8.4 RCU Variants

- Classic RCU: Grace period detection via quiescent states

- SRCU (Sleepable RCU): Readers can sleep in critical sections

- QRCU: Optimized for quick grace periods

- User-space RCU (URCU): Library implementation for user-space programs

RCU is extremely fast for readers (often zero overhead) but requires careful design: updates create new versions rather than modifying in place.

9. Performance Considerations

9.1 False Sharing

When multiple atomics share a cache line, updates cause the line to bounce between cores:

struct BadCounters {

atomic<int> counter1; // Same cache line!

atomic<int> counter2;

};

Fix with padding:

struct GoodCounters {

alignas(64) atomic<int> counter1;

alignas(64) atomic<int> counter2;

};

9.2 Contention and Backoff

High contention leads to many CAS failures. Backoff strategies help:

- Exponential backoff: Wait longer after each failure

- Random backoff: Add randomness to reduce collision probability

- Adaptive backoff: Adjust based on observed contention

void push_with_backoff(Stack* s, int val) {

int backoff = MIN_BACKOFF;

while (!try_push(s, val)) {

for (int i = 0; i < backoff; i++) {

cpu_relax(); // Pause instruction

}

backoff = min(backoff * 2, MAX_BACKOFF);

}

}

9.3 Helping vs. Waiting

Lock-free algorithms often have threads “help” each other complete operations. This ensures progress but can cause redundant work. The trade-off:

- More helping = better progress guarantees but more cache traffic

- Less helping = better throughput under low contention but worse tail latency

9.4 NUMA Considerations

Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) architectures add complexity:

- Atomics on remote memory are slower (cross-socket traffic)

- Consider NUMA-aware data structure placement

- Thread-local structures with occasional synchronization may outperform global lock-free structures

10. Testing and Verification

Lock-free code is notoriously hard to test. Bugs may manifest only under specific timing conditions.

10.1 Stress Testing

Run many threads performing random operations for extended periods:

void stress_test(Stack* s) {

parallel_for(num_threads, [&](int tid) {

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

if (rand() % 2) {

push(s, tid * iterations + i);

} else {

pop(s);

}

}

});

}

Check invariants after the test: correct item count, no duplicates, no lost items.

10.2 ThreadSanitizer (TSan)

Compiler-based tools detect data races:

clang++ -fsanitize=thread -g -O1 my_code.cpp

./a.out # Reports races

TSan instruments memory accesses and tracks happens-before relationships. False negatives are possible, but it catches many real bugs.

10.3 Model Checking

Tools like CDSChecker and GenMC explore all possible interleavings:

// Test with CDSChecker

void test_stack() {

Stack s;

thread t1([&]{ push(&s, 1); });

thread t2([&]{ push(&s, 2); });

thread t3([&]{ pop(&s); });

t1.join(); t2.join(); t3.join();

// CDSChecker tries all interleavings

}

Model checkers find subtle bugs but have exponential state space; they work best on small code fragments.

10.4 Formal Verification

For critical code, prove correctness mathematically:

- TLA+: Specify and model-check concurrent algorithms

- Coq/Iris: Full formal proofs of lock-free data structures

- SPIN: Model checker for protocol verification

Major lock-free data structures (Michael-Scott queue, Harris list) have been formally verified.

11. Real-World Implementations

11.1 Java ConcurrentLinkedQueue

Java’s ConcurrentLinkedQueue implements a variation of the Michael-Scott queue:

ConcurrentLinkedQueue<Integer> queue = new ConcurrentLinkedQueue<>();

queue.offer(1); // Lock-free enqueue

Integer val = queue.poll(); // Lock-free dequeue

Java’s garbage collector handles memory reclamation, simplifying the implementation significantly.

11.2 Crossbeam (Rust)

Rust’s crossbeam crate provides lock-free data structures with safe memory reclamation:

use crossbeam::queue::SegQueue;

let queue: SegQueue<i32> = SegQueue::new();

queue.push(1);

let val = queue.pop();

Crossbeam uses epoch-based reclamation, integrated with Rust’s ownership system.

11.3 Intel TBB

Intel’s Threading Building Blocks includes lock-free containers:

tbb::concurrent_queue<int> queue;

queue.push(1);

int val;

bool success = queue.try_pop(val);

TBB’s containers are highly optimized for Intel architectures.

11.4 Folly (Facebook)

Facebook’s Folly library includes production-grade lock-free structures:

folly::MPMCQueue<int> queue(1024); // Multi-producer multi-consumer

queue.write(42);

int val;

queue.read(val);

Folly’s implementations emphasize practical performance over theoretical elegance.

12. When to Use Lock-Free

12.1 Good Use Cases

- High-contention scenarios: Many threads competing for the same data

- Real-time systems: Bounded progress guarantees matter

- Interrupt/signal handlers: Can’t safely acquire locks

- Heterogeneous timing: Some threads much faster than others

- Kernel code: Locks are expensive; RCU is often used instead

12.2 Avoid When

- Low contention: Locks are simpler and often faster

- Complex operations: Multi-word updates are hard to make lock-free

- Debugging priority: Lock-free bugs are extremely hard to diagnose

- Memory-constrained: Lock-free often requires extra memory (versions, pointers)

- Team expertise: Lock-free code requires specialized knowledge to maintain

12.3 Hybrid Approaches

Many systems use hybrid approaches:

- Lock-free fast path, lock-based slow path

- Read-mostly data with RCU; occasional locked updates

- Per-thread lock-free structures with locked synchronization between threads

- Lock-free for hot operations, locks for complex/rare operations

13. Common Pitfalls

13.1 Memory Ordering Mistakes

Using memory_order_relaxed everywhere is tempting but wrong:

// BUG: No synchronization

data = 42;

flag.store(true, memory_order_relaxed);

// Other thread

while (!flag.load(memory_order_relaxed));

print(data); // Might not see 42!

Always think carefully about what orderings are required.

13.2 ABA Blindness

Assuming pointer comparison is sufficient:

// BUG: ABA problem

if (CAS(&head, old_head, old_head->next)) {

// old_head might have been freed and reused!

free(old_head);

}

Use tagged pointers, hazard pointers, or other ABA prevention.

13.3 Forgetting Memory Reclamation

Lock-free doesn’t mean garbage collection:

// BUG: When can we free removed nodes?

Node* removed = pop();

free(removed); // Might still be accessed by other threads!

Always have a reclamation strategy (hazard pointers, epochs, RCU).

13.4 Over-Optimization

Optimizing memory orderings prematurely:

// Premature optimization: hard to reason about

x.store(1, memory_order_release);

y.store(2, memory_order_relaxed); // Is this safe?

Start with sequential consistency, measure, then optimize with extreme care.

13.5 Ignoring Contention Effects

A “lock-free” structure under extreme contention can perform worse than a simple lock:

// Many threads CASing the same location = high failure rate

while (!CAS(&counter, old, old + 1)) {

old = counter; // Retry loop, high cache traffic

}

Consider per-thread aggregation or combining techniques.

14. Advanced Topics

14.1 Universal Constructions

Any sequential data structure can be made lock-free using a “universal construction”:

- Represent operations as a log of commands

- Use consensus to order commands

- Apply commands to derive current state

This is theoretically interesting but impractical—purpose-built lock-free structures are much faster.

14.2 Combining

Under high contention, have threads combine their operations:

- Thread A wants to increment

- Thread B also wants to increment

- Thread B gives its operation to A (combining)

- A performs both increments in one CAS

- A returns results to B

Flat-combining and the combining tree exploit this idea for high throughput.

14.3 Elimination

Some operations cancel out:

- Thread A is pushing X

- Thread B is popping

- Instead of both hitting the stack, exchange directly: A gives X to B

Elimination backoff stacks use this to scale under high push/pop contention.

14.4 Transactional Memory

Hardware transactional memory (HTM) provides an alternative:

_xbegin(); // Start transaction

// Multiple reads/writes—all atomic

_xend(); // Commit transaction

HTM is available on recent Intel (TSX) and IBM POWER CPUs. It simplifies lock-free programming but has limitations (transaction size, abort handling).

15. Future Directions

15.1 Persistent Lock-Free Structures

With non-volatile memory (NVM), lock-free structures need crash consistency:

- Flush cache lines in the right order

- Handle partial writes on crash

- Recovery protocols for lock-free algorithms

This is an active research area with libraries like PMDK providing primitives.

15.2 Lock-Free in Managed Languages

Languages with garbage collection simplify lock-free programming (no manual reclamation), but introduce new challenges:

- GC pauses can delay threads, affecting progress

- Compiler reorderings need careful annotation

- Reference counting overhead

Research continues on GC-aware lock-free designs.

15.3 Formal Methods Integration

As lock-free code becomes more common, better tooling is needed:

- Automated verification of memory ordering correctness

- Synthesis of lock-free implementations from specifications

- Testing frameworks aware of weak memory models

16. Real-World Case Studies

Understanding theory is valuable, but seeing how lock-free techniques solve real problems cements the knowledge. Let’s examine several case studies from production systems.

16.1 Facebook’s Folly Library

Facebook’s Folly library provides battle-tested lock-free data structures. Their AtomicHashMap is particularly instructive. Rather than trying to make a general-purpose hash map lock-free (which is extremely complex), they made specific trade-offs:

- The map can grow but never shrink

- Deletions mark entries as tombstones rather than actually removing them

- Inserts are lock-free; the map uses a technique called “linear probing with quadratic reprobe”

This design accepts memory overhead in exchange for lock-free reads and writes. For Facebook’s use case—high-read workloads with infrequent deletions—this trade-off makes sense. The map achieves millions of operations per second on modern hardware.

16.2 Disruptor Pattern in Trading

LMAX Exchange developed the Disruptor pattern for their trading platform. At its core is a lock-free ring buffer that achieves remarkable throughput—over 6 million transactions per second on a single thread.

The key insight is eliminating the need for locks by carefully partitioning responsibilities:

- A single producer writes to the buffer, updating a sequence counter atomically

- Multiple consumers each maintain their own sequence number

- Consumers can read any entry up to the producer’s sequence minus a buffer length

- Memory barriers ensure visibility without locks

The Disruptor achieves performance by keeping data in cache lines, avoiding false sharing, and using memory-mapped files for persistence. It demonstrates that sometimes the best lock-free design is one that avoids contention entirely through careful architecture.

16.3 Linux Kernel’s Lockless Page Cache

The Linux kernel’s page cache uses a clever lock-free technique called SLAB_TYPESAFE_BY_RCU. Objects in the page cache can be freed and reallocated while readers are still accessing them. This sounds dangerous, but RCU’s rules make it safe:

- Readers hold an RCU read-side lock (which is just a preempt-disable on non-preemptible kernels)

- Writers must wait for all readers to finish before truly freeing an object

- Objects are always valid memory, even if they’ve been repurposed

This allows the page cache to achieve remarkable scalability. On a 128-core system, the page cache can handle millions of lookups per second without any lock contention.

16.4 ConcurrentSkipListMap in Java

Java’s ConcurrentSkipListMap implements a lock-free sorted map using skip lists. Skip lists are particularly amenable to lock-free implementation because their probabilistic structure means most operations only touch a small number of nodes.

The implementation uses CAS to atomically update forward pointers. A key technique is the use of marker nodes during deletion:

- To delete a node, first CAS a marker node in after it

- Other threads see the marker and help complete the deletion

- Finally, CAS the predecessor’s pointer to skip both the deleted node and marker

This “helping” protocol is common in lock-free algorithms. When a thread detects an in-progress operation by another thread, it helps complete that operation before proceeding. This ensures progress even if the original thread stalls.

17. Debugging Lock-Free Code in Production

When lock-free code misbehaves in production, standard debugging techniques often fail. Here’s a practical guide to debugging these subtle issues.

17.1 Gathering Evidence

Lock-free bugs often manifest as:

- Memory corruption detected far from the cause

- ABA-related issues that appear as impossible states

- Performance degradation under specific load patterns

- Rare crashes that never reproduce in testing

Start by gathering statistics:

- Count CAS failures per operation type

- Track retry loop iterations

- Measure latency percentiles, not just averages

- Log “impossible” states before asserting

17.2 Using Core Dumps Effectively

When a lock-free algorithm corrupts memory, the crash site rarely indicates the root cause. Effective debugging requires:

- Capture enough state: Include atomic counters, version tags, and recent operations

- Add sentinel values: Fill unused memory with recognizable patterns (0xDEADBEEF)

- Implement operation logging: A lock-free ring buffer of recent operations helps reconstruction

17.3 Production Tracing

For bugs that don’t crash, distributed tracing can help. Instrument your lock-free operations with:

- Operation start/end timestamps

- Thread IDs and processor affinity

- Memory addresses being accessed

- CAS expected vs. actual values

Tools like eBPF on Linux allow adding this instrumentation without rebuilding your application.

17.4 Canary Deployments

Given the difficulty of reproducing lock-free bugs, canary deployments are essential:

- Deploy to a small percentage of production traffic

- Monitor closely for anomalies

- Have automatic rollback triggers

- Gradually increase deployment percentage

18. Building Your Lock-Free Intuition

Developing intuition for lock-free programming takes time. Here are exercises and mental models that help.

18.1 Mental Models

The Time-Slice Model: Imagine every line of code can be paused and another thread can execute arbitrary code before resuming. If your algorithm is correct under this model, it handles interleaving correctly.

The Reordering Model: Imagine a malicious compiler and CPU that reorder every operation that the memory model allows. Use memory barriers and proper orderings to constrain what’s possible.

The Visibility Model: Imagine each CPU has its own copy of memory that synchronizes with others only through explicit synchronization. This models store buffers and cache coherency.

18.2 Practice Exercises

Lock-free counter: Implement a counter that supports increment, decrement, and read. Verify it never produces a value outside the range of values it’s had.

SPSC queue: Implement a single-producer, single-consumer queue. This is the simplest lock-free queue and builds foundation.

Lock-free set: Implement a set supporting add, remove, and contains. Handle the deletion problem carefully.

Reproduce the ABA bug: Write code that demonstrates the ABA problem, then fix it with version counters.

18.3 Code Review Checklist

When reviewing lock-free code, check:

- Is every atomic operation using the correct memory ordering?

- Are all pointer manipulations protected against ABA?

- Is memory reclamation handled safely?

- Can a thread see a partially-constructed object?

- What happens if a thread dies mid-operation?

- Have spin loops been tested for livelock?

- Is the algorithm formally verified or well-tested?

19. Summary

Lock-free data structures eliminate blocking, providing progress guarantees that traditional locks cannot. The key concepts:

- CAS is the foundation: Compare-and-swap enables atomic updates without locks

- Memory ordering matters: Atomicity alone isn’t enough; proper fences and orderings prevent subtle bugs

- ABA is real: Detect or prevent the ABA problem in any lock-free pointer manipulation

- Memory reclamation is hard: Hazard pointers, epoch-based reclamation, or RCU are essential

- Test rigorously: Lock-free bugs are timing-dependent; use stress testing, sanitizers, and model checkers

Lock-free programming is a powerful tool, but not a silver bullet. Use it when the benefits—latency consistency, fault tolerance, progress guarantees—outweigh the complexity costs. For most applications, well-implemented locks remain the right choice. But for the systems that need them, lock-free data structures enable performance and reliability that locks simply cannot match.

The journey from understanding basic CAS operations to implementing production-ready lock-free data structures is long. Start with simple algorithms, build intuition through practice, and always verify your implementations thoroughly. The complexity is real, but so are the rewards: systems that are faster, more predictable, and more resilient than their lock-based counterparts.

Whether you’re building a high-frequency trading system, an operating system kernel, or a distributed database, understanding lock-free techniques adds an essential tool to your concurrency toolkit. The field continues to evolve with new hardware capabilities, new reclamation techniques, and better verification tools. Master the fundamentals presented here, and you’ll be well-prepared to tackle the next generation of concurrent systems.