Network Sockets and the TCP/IP Stack: How Data Travels Across Networks

A comprehensive exploration of network programming internals, from socket system calls through the TCP/IP protocol stack to the network interface. Understand connection establishment, flow control, and the kernel's role in networking.

Every web request, database query, and API call travels through the network stack. The simple act of opening a connection hides layers of protocol machinery handling packet routing, reliable delivery, congestion control, and flow management. Understanding how sockets work and how data traverses the TCP/IP stack illuminates why networks behave as they do and how to build efficient networked applications.

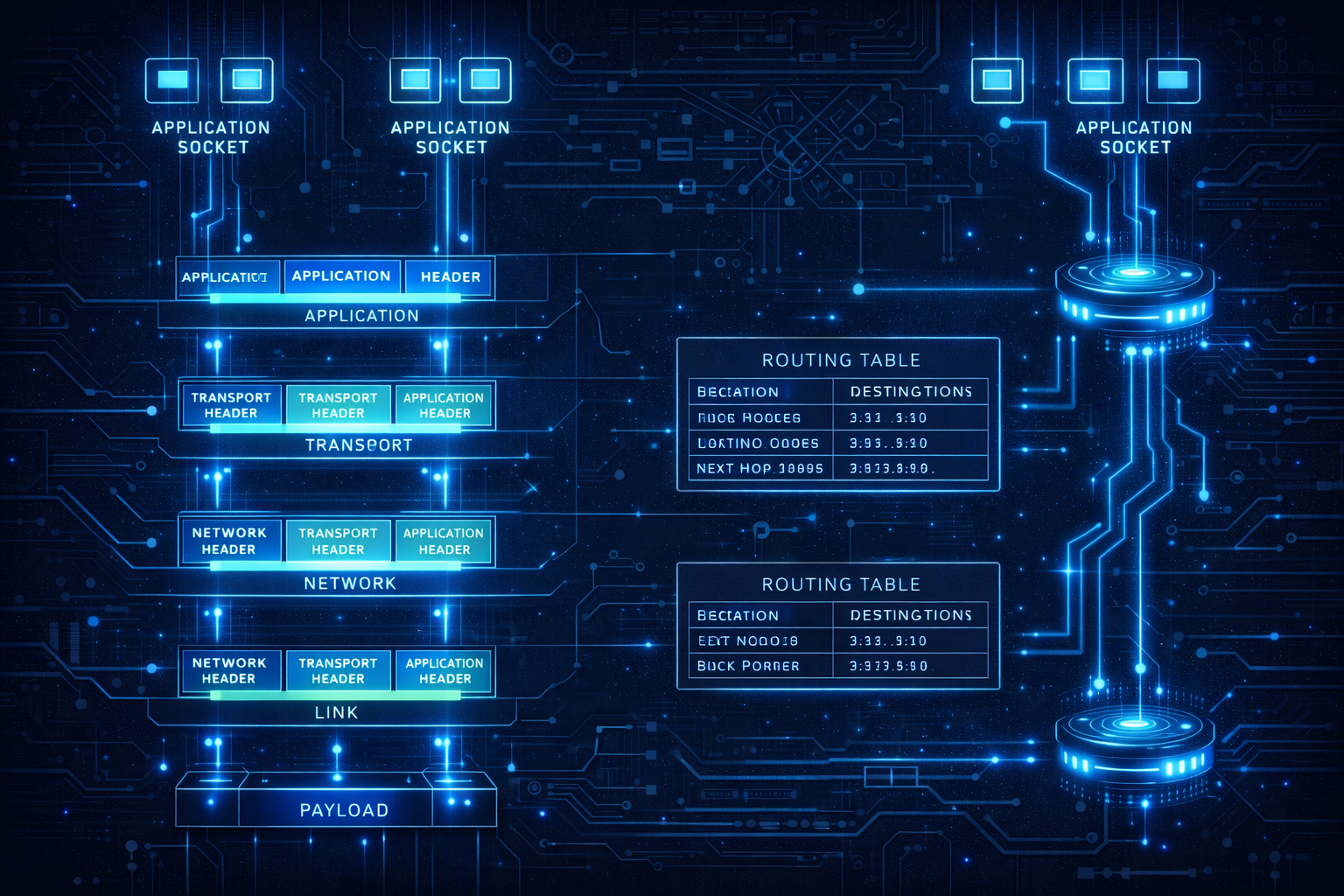

1. The Network Stack Overview

Before diving into details, let’s see the complete picture.

1.1 The OSI and TCP/IP Models

OSI Model TCP/IP Model Examples

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐

│ Application │ │ │ HTTP, DNS, SSH

├─────────────────┤ │ Application │

│ Presentation │ │ │ TLS, JSON, XML

├─────────────────┤ │ │

│ Session │ │ │ Sockets API

├─────────────────┤ ├─────────────────┤

│ Transport │ │ Transport │ TCP, UDP

├─────────────────┤ ├─────────────────┤

│ Network │ │ Internet │ IP, ICMP

├─────────────────┤ ├─────────────────┤

│ Data Link │ │ │ Ethernet, WiFi

├─────────────────┤ │ Link │

│ Physical │ │ │ Cables, Radio

└─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘

Data flow (sending):

Application → Transport → Network → Link → Physical → Wire

Data flow (receiving):

Wire → Physical → Link → Network → Transport → Application

1.2 Encapsulation

Each layer wraps data in its own header:

Application data:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ HTTP Request │

│ "GET /index.html HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: example.com..." │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Transport layer (TCP) adds header:

┌──────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TCP Header │ HTTP Request │

│ (20 bytes) │ │

└──────────────┴─────────────────────────────────────────┘

Network layer (IP) adds header:

┌──────────────┬──────────────┬──────────────────────────┐

│ IP Header │ TCP Header │ HTTP Request │

│ (20 bytes) │ (20 bytes) │ │

└──────────────┴──────────────┴──────────────────────────┘

Link layer (Ethernet) adds header and trailer:

┌──────────────┬──────────────┬──────────────┬────────────────────┬─────────┐

│ Eth Header │ IP Header │ TCP Header │ HTTP Request │Eth Trail│

│ (14 bytes) │ (20 bytes) │ (20 bytes) │ │(4 bytes)│

└──────────────┴──────────────┴──────────────┴────────────────────┴─────────┘

This complete unit is a "frame" ready for transmission.

1.3 Kernel Networking Components

Linux network stack architecture:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Space │

│ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐ │

│ │ Application │ │ Application │ │ Application │ │

│ │ (browser) │ │ (server) │ │ (database) │ │

│ └──────┬───────┘ └──────┬───────┘ └────────┬─────────┘ │

└─────────┼─────────────────┼───────────────────┼─────────────┘

│ Socket API │ │

──────────┼─────────────────┼───────────────────┼──────────────

▼ ▼ ▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Socket Layer │ │

│ │ (struct socket, file descriptor) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┘ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Protocol Layer (TCP/UDP) │ │

│ │ (struct sock, connection state, buffers) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┘ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ IP Layer │ │

│ │ (routing, fragmentation) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┘ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Network Device Layer │ │

│ │ (driver interface, queues) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────┘

▼

┌─────────────────┐

│ NIC Hardware │

└─────────────────┘

2. The Socket API

Sockets provide the programming interface to the network.

2.1 Socket System Calls

// Server side

int server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0); // Create socket

struct sockaddr_in addr = {

.sin_family = AF_INET,

.sin_port = htons(8080),

.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY

};

bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof(addr)); // Bind to port

listen(server_fd, 128); // Mark as listening, backlog = 128

int client_fd = accept(server_fd, NULL, NULL); // Accept connection

// client_fd is a new socket for this connection

char buffer[1024];

ssize_t n = read(client_fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer)); // Receive data

write(client_fd, "Hello", 5); // Send data

close(client_fd); // Close connection

close(server_fd); // Close listening socket

// Client side

int sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_in server = {

.sin_family = AF_INET,

.sin_port = htons(8080)

};

inet_pton(AF_INET, "192.168.1.1", &server.sin_addr);

connect(sock, (struct sockaddr*)&server, sizeof(server)); // Connect

write(sock, "Hello", 5); // Send

read(sock, buffer, sizeof(buffer)); // Receive

close(sock);

2.2 Socket Data Structures

Kernel socket structures:

struct socket (VFS interface):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ state: SS_CONNECTED │

│ type: SOCK_STREAM │

│ flags: various options │

│ ops: pointer to protocol operations │

│ sk: pointer to struct sock (protocol layer) │

│ file: pointer to struct file (for fd) │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

struct sock (protocol layer):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Protocol state (TCP: ESTABLISHED, etc.) │

│ Source/destination addresses and ports │

│ Send buffer (sk_write_queue) │

│ Receive buffer (sk_receive_queue) │

│ Timers (retransmit, keepalive, etc.) │

│ Congestion control state │

│ Window sizes │

│ Sequence numbers │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

struct sk_buff (packet buffer):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Pointers: head, data, tail, end │

│ Protocol headers at various offsets │

│ Reference count │

│ Device reference │

│ Timestamp │

│ Actual packet data follows │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

2.3 File Descriptor Integration

Sockets are file descriptors:

Process file descriptor table:

┌─────┬───────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ fd │ struct file* │

├─────┼───────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0 │ → stdin (terminal) │

│ 1 │ → stdout (terminal) │

│ 2 │ → stderr (terminal) │

│ 3 │ → socket (struct socket → TCP connection) │

│ 4 │ → regular file (/tmp/data.txt) │

│ 5 │ → socket (listening server socket) │

└─────┴───────────────────────────────────────────┘

Because sockets are fds:

- read()/write() work on sockets

- select()/poll()/epoll work on sockets

- Can pass sockets between processes (via Unix sockets)

- close() closes the connection

- dup()/dup2() create socket aliases

Socket-specific operations:

- send()/recv() with flags

- sendto()/recvfrom() for UDP

- sendmsg()/recvmsg() for advanced use

- getsockopt()/setsockopt() for options

2.4 Blocking vs Non-Blocking

// Blocking (default): calls wait until complete

read(sock, buf, len); // Blocks until data available

// Non-blocking: calls return immediately

int flags = fcntl(sock, F_GETFL, 0);

fcntl(sock, F_SETFL, flags | O_NONBLOCK);

ssize_t n = read(sock, buf, len);

if (n == -1 && errno == EAGAIN) {

// No data available, try again later

}

// Or set at socket creation

int sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM | SOCK_NONBLOCK, 0);

// Common pattern with epoll:

int epfd = epoll_create1(0);

struct epoll_event ev = {

.events = EPOLLIN | EPOLLET, // Edge-triggered

.data.fd = sock

};

epoll_ctl(epfd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, sock, &ev);

struct epoll_event events[MAX_EVENTS];

int nfds = epoll_wait(epfd, events, MAX_EVENTS, -1);

for (int i = 0; i < nfds; i++) {

handle_event(events[i]);

}

3. TCP Connection Lifecycle

Understanding TCP’s reliable connection protocol.

3.1 Three-Way Handshake

Connection establishment:

Client Server

│ │

│ ──────── SYN (seq=x) ──────────► │

│ │

│ ◄─── SYN-ACK (seq=y, ack=x+1) ── │

│ │

│ ──────── ACK (ack=y+1) ────────► │

│ │

ESTABLISHED ESTABLISHED

Sequence numbers:

- Client picks random initial sequence number (ISN): x

- Server picks its own ISN: y

- Each side acknowledges the other's ISN + 1

- Prevents old duplicate packets from being accepted

SYN queue and accept queue:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Server Kernel │

│ │

│ Incoming SYN: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ SYN Queue (half-open) │ ← SYN received │

│ │ Connection 1 (SYN_RECV) │ SYN-ACK sent │

│ │ Connection 2 (SYN_RECV) │ │

│ │ Connection 3 (SYN_RECV) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ ACK received │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Accept Queue (established) │ │

│ │ Connection A (ESTABLISHED) │ ← Ready for │

│ │ Connection B (ESTABLISHED) │ accept() │

│ └─────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ accept() returns │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

3.2 Data Transfer

Reliable data transfer:

Sender Receiver

│ │

│ ─── Data (seq=1000, len=1000) ──────► │

│ │

│ ◄─────── ACK (ack=2000) ──────────── │

│ │

│ ─── Data (seq=2000, len=1000) ──────► │

│ ─── Data (seq=3000, len=1000) ──────► │

│ ─── Data (seq=4000, len=1000) ──────► │

│ │

│ ◄─────── ACK (ack=5000) ──────────── │ (cumulative)

│ │

Cumulative acknowledgment:

- ACK number = next expected byte

- ACK 5000 means "received all bytes up to 4999"

- Multiple segments can be ACKed with single ACK

Retransmission:

- Sender sets timer for each segment

- If ACK not received in time, retransmit

- Exponential backoff on repeated failures

3.3 Connection Termination

Four-way handshake for graceful close:

Client Server

│ │

│ ───────── FIN (seq=x) ─────────► │

│ │

FIN_WAIT_1 CLOSE_WAIT

│ │

│ ◄──────── ACK (ack=x+1) ──────── │

│ │

FIN_WAIT_2 (Server may send more data)

│ │

│ ◄──────── FIN (seq=y) ────────── │

│ │

TIME_WAIT LAST_ACK

│ │

│ ───────── ACK (ack=y+1) ────────► │

│ │

(wait 2×MSL) CLOSED

│ │

CLOSED │

TIME_WAIT:

- Lasts 2 × Maximum Segment Lifetime (typically 60 seconds)

- Ensures final ACK reaches server

- Prevents old duplicate packets from being accepted

- Can cause "address already in use" on quick restart

- SO_REUSEADDR socket option helps

3.4 TCP State Machine

Complete TCP state diagram:

┌──────────────┐

│ CLOSED │

└──────┬───────┘

passive open │ active open

(listen) │ (connect)

┌───────────┴───────────┐

▼ ▼

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ LISTEN │ │ SYN_SENT │

└──────┬───────┘ └──────┬───────┘

rcv SYN │ │ rcv SYN-ACK

send SYN-ACK │ send ACK

│ ┌─────────────┘

▼ ▼

┌──────────────────────┐

│ SYN_RECEIVED │

└──────────┬───────────┘

rcv ACK │

▼

┌──────────────────────┐

│ ESTABLISHED │ ← Normal data transfer

└──────────┬───────────┘

close │ rcv FIN

send FIN │ send ACK

┌─────────────────┴─────────────────┐

▼ ▼

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ FIN_WAIT_1 │ │ CLOSE_WAIT │

└──────┬───────┘ └──────┬───────┘

│ │ close

▼ │ send FIN

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────┴───────┐

│ FIN_WAIT_2 │ │ LAST_ACK │

└──────┬───────┘ └──────┬───────┘

rcv FIN │ rcv ACK │

send ACK│ │

▼ ▼

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ TIME_WAIT │ │ CLOSED │

└──────┬───────┘ └──────────────┘

timeout │

▼

┌──────────────┐

│ CLOSED │

└──────────────┘

4. TCP Flow Control and Congestion Control

Preventing overwhelming receivers and networks.

4.1 Flow Control: Receive Window

Receive window prevents sender from overwhelming receiver:

Receiver advertises available buffer space:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Receiver Buffer (64KB) │

│ ┌──────────────────────────┬───────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Data waiting for │ Available space │ │

│ │ application read │ (receive window) │ │

│ │ 32KB │ 32KB │ │

│ └──────────────────────────┴───────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ACK packet includes: Window = 32768 │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Sender side:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Must keep: unacked_data + in_flight ≤ receiver_window │

│ │

│ If window = 0: Stop sending, probe periodically │

│ As receiver reads data: Window opens, ACK sent │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Window scaling (for high bandwidth-delay networks):

- Original window: 16 bits = max 64KB

- Window scale option: Multiply by 2^scale

- Scale up to 14 = 64KB × 16384 = 1GB window

4.2 Congestion Control

Preventing network congestion collapse:

Congestion window (cwnd): Sender-side limit

- Independent of receive window

- Grows when network seems uncongested

- Shrinks on packet loss (sign of congestion)

Effective window = min(cwnd, receive_window)

Classic algorithms:

Slow Start:

- Initial cwnd = 1-10 MSS (Maximum Segment Size)

- Double cwnd each RTT (exponential growth)

- Until: loss occurs OR cwnd > ssthresh

Congestion Avoidance:

- Linear growth: cwnd += 1 per RTT

- After loss: ssthresh = cwnd/2, restart

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ cwnd │

│ │ ×(loss) │

│ │ ╱ │ │

│ │ ╱ │ │

│ │ ╱ │ Linear │

│ │ ╱ │ ╱ │

│ │ ╱ │ ╱ │

│ │ ╱ Slow start ╱ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────── time │

│ Exponential growth ssthresh │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

4.3 Modern Congestion Control

CUBIC (Linux default):

- Designed for high bandwidth-delay product networks

- Cubic function of time since last loss

- More aggressive window growth than classic TCP

- Used by most Linux servers

BBR (Bottleneck Bandwidth and RTT):

- Developed by Google

- Model-based rather than loss-based

- Estimates bandwidth and RTT

- Maintains low queue occupancy

- Better performance on lossy links

Comparison:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Algorithm │ Loss-based │ Queue │ Fairness │

├────────────┼────────────┼───────┼─────────────────────┤

│ Reno │ Yes │ High │ Poor with others │

│ CUBIC │ Yes │ High │ Good with CUBIC │

│ BBR │ No │ Low │ Issues with others │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Setting congestion control:

sysctl net.ipv4.tcp_congestion_control=bbr

# Or per-socket:

setsockopt(sock, IPPROTO_TCP, TCP_CONGESTION, "bbr", 3);

4.4 Nagle’s Algorithm and Delayed ACKs

Nagle's algorithm (reduce small packets):

- If there's unacknowledged data AND new data is small:

Buffer it until ACK arrives or buffer fills

- Prevents sending many tiny packets

Delayed ACKs:

- Don't ACK every packet immediately

- Wait up to 40ms for more data to piggyback ACK

- Or ACK after every 2 full-size segments

The interaction problem:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Client (Nagle) Server (Delayed ACK) │

│ │

│ send(100 bytes) ──────► (received, waiting for more) │

│ send(100 bytes) │ │

│ │ waiting for ACK │ waiting 40ms to ACK │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ 40ms delay before next data sent! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Solutions:

- TCP_NODELAY: Disable Nagle (send immediately)

- TCP_QUICKACK: Disable delayed ACK

- Batch writes: Larger writes avoid the issue

setsockopt(sock, IPPROTO_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, &one, sizeof(one));

5. The IP Layer

Network layer handles addressing and routing.

5.1 IP Packet Structure

IPv4 Header (20-60 bytes):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 0 1 2 │

│ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 ... │

│ ├─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┼─┤ │

│ │Version│ IHL │ DSCP │ECN│ Total Length │ │

│ ├───────────────┼───────────┴───┴─────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Identification │Flags│ Frag Offset │ │

│ ├───────────────┼─────────────────┴───────────────────┤ │

│ │ TTL │ Protocol │ Header Checksum │ │

│ ├───────────────┴─────────────────┴───────────────────┤ │

│ │ Source Address │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Destination Address │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Options (if any) │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key fields:

- Version: 4 for IPv4, 6 for IPv6

- TTL: Decremented at each hop, prevents loops

- Protocol: 6 = TCP, 17 = UDP, 1 = ICMP

- Addresses: 32-bit source and destination

5.2 IP Fragmentation

Large packets may need fragmentation:

Original packet (4000 bytes data, MTU = 1500):

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ IP Header │ 4000 bytes of data │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Fragmented into 3 packets:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ IP │ Frag 0: 1480 bytes │ Offset = 0, MF = 1

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ IP │ Frag 1: 1480 bytes │ Offset = 1480, MF = 1

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ IP │ Frag 2: 1040 bytes │ Offset = 2960, MF = 0

└─────────────────────────────┘

Problems with fragmentation:

- Receiver must reassemble (buffer, timeout)

- One lost fragment = entire packet lost

- Security issues (fragment attacks)

- Performance overhead

Modern approach: Path MTU Discovery

- Set "Don't Fragment" (DF) bit

- If router can't forward, it sends ICMP "too big"

- Sender reduces packet size

- Avoids fragmentation in network

5.3 Routing

Routing table lookup:

$ ip route show

default via 192.168.1.1 dev eth0

192.168.1.0/24 dev eth0 proto kernel scope link src 192.168.1.100

10.0.0.0/8 via 192.168.1.254 dev eth0

For destination 10.5.3.2:

1. Check most specific matching prefix

2. 10.0.0.0/8 matches (8 bits)

3. Next hop: 192.168.1.254 via eth0

Routing decision in kernel:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Packet arrives │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │

│ │ Is dest local? │ │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ │

│ Yes │ No │

│ ┌─────────┴─────────┐ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ Deliver locally Route lookup │

│ (pass up stack) (forward out interface) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

5.4 ARP: Address Resolution

Mapping IP addresses to MAC addresses:

Host wants to send to 192.168.1.1:

1. Check ARP cache: ip neigh show

2. If not found, broadcast ARP request:

"Who has 192.168.1.1? Tell 192.168.1.100"

3. Owner responds (unicast):

"192.168.1.1 is at aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff"

4. Cache the mapping, send packet

ARP cache:

$ ip neigh show

192.168.1.1 dev eth0 lladdr aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff REACHABLE

192.168.1.50 dev eth0 lladdr 11:22:33:44:55:66 STALE

States:

- REACHABLE: Recently confirmed

- STALE: May need refresh

- INCOMPLETE: ARP request sent, waiting

- FAILED: No response received

6. UDP: The Simple Alternative

When you don’t need TCP’s guarantees.

6.1 UDP Characteristics

UDP Header (8 bytes only!):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Source Port │ Destination Port │

├──────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────┤

│ Length │ Checksum │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

UDP provides:

✓ Multiplexing (ports)

✓ Optional checksum

✗ No connection setup

✗ No reliability (no retransmission)

✗ No ordering guarantee

✗ No flow control

✗ No congestion control

UDP code:

int sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0); // DGRAM = UDP

// No connect needed (but can use connect for default dest)

sendto(sock, data, len, 0, &dest_addr, addr_len);

recvfrom(sock, buf, size, 0, &src_addr, &addr_len);

6.2 When to Use UDP

Good use cases for UDP:

DNS queries:

- Small request/response

- Timeout and retry at application level

- Connection setup overhead > actual data

Video/audio streaming:

- Real-time, can't wait for retransmissions

- Missing frame less bad than delayed frame

- Application handles packet loss gracefully

Gaming:

- Low latency critical

- Old state updates can be skipped

- Game protocol handles reliability if needed

QUIC (HTTP/3):

- UDP-based transport

- Implements reliability on top

- Avoids TCP head-of-line blocking

- Faster connection establishment

6.3 UDP Reliability When Needed

Building reliability on UDP:

Application-level acknowledgment:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ struct packet { │

│ uint32_t sequence; // Packet number │

│ uint32_t ack; // What we've received │

│ uint16_t flags; // Control flags │

│ uint8_t data[]; // Payload │

│ }; │

│ │

│ Sender: │

│ - Track sent packets and timestamps │

│ - Retransmit if no ACK within timeout │

│ - Implement own congestion control │

│ │

│ Receiver: │

│ - Track received sequence numbers │

│ - Reorder if needed │

│ - Send ACKs (possibly with SACK) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Libraries: QUIC, KCP, ENet, Reliable UDP implementations

6.4 Multicast and Broadcast

UDP supports one-to-many communication:

Broadcast (same subnet only):

struct sockaddr_in addr;

addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_BROADCAST; // 255.255.255.255

int broadcast = 1;

setsockopt(sock, SOL_SOCKET, SO_BROADCAST, &broadcast, sizeof(broadcast));

sendto(sock, data, len, 0, &addr, sizeof(addr));

Multicast (across networks):

// Join a multicast group

struct ip_mreq mreq;

mreq.imr_multiaddr.s_addr = inet_addr("239.0.0.1");

mreq.imr_interface.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

setsockopt(sock, IPPROTO_IP, IP_ADD_MEMBERSHIP, &mreq, sizeof(mreq));

// Send to multicast group

struct sockaddr_in mcast_addr;

mcast_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("239.0.0.1");

sendto(sock, data, len, 0, &mcast_addr, sizeof(mcast_addr));

Use cases:

- Service discovery (mDNS, SSDP)

- Live video/audio streaming

- Financial data feeds

- Cluster heartbeats

IGMP (Internet Group Management Protocol):

- Hosts tell routers which groups they want

- Routers only forward multicast to interested subnets

- Reduces unnecessary network traffic

7. Network Performance

Understanding and optimizing network throughput.

7.1 Bandwidth-Delay Product

BDP = Bandwidth × Round-Trip Time

Example:

100 Mbps link, 50ms RTT

BDP = 100,000,000 bits/s × 0.050 s = 5,000,000 bits = 625 KB

What this means:

- 625 KB of data can be "in flight" at any time

- Need send/receive buffers at least this large

- TCP window must be at least BDP for full utilization

If buffer < BDP:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Sender Receiver │

│ ┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ │

│ │ Buffer │─── data ───────────►│ Buffer │ │

│ │ 64 KB │ │ 64 KB │ │

│ └────────┘◄── ACK ─────────────└────────┘ │

│ │

│ With 625KB BDP but 64KB buffer: │

│ Can only send 64KB before waiting for ACK │

│ Utilization: 64/625 ≈ 10% of available bandwidth! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

7.2 Buffer Sizing

Socket buffer tuning:

# View current settings

sysctl net.core.rmem_max

sysctl net.core.wmem_max

sysctl net.ipv4.tcp_rmem

sysctl net.ipv4.tcp_wmem

# tcp_rmem and tcp_wmem: min, default, max

net.ipv4.tcp_rmem = 4096 131072 6291456

net.ipv4.tcp_wmem = 4096 16384 4194304

Per-socket setting:

int size = 4 * 1024 * 1024; // 4 MB

setsockopt(sock, SOL_SOCKET, SO_RCVBUF, &size, sizeof(size));

setsockopt(sock, SOL_SOCKET, SO_SNDBUF, &size, sizeof(size));

Auto-tuning:

- Linux automatically adjusts buffer sizes

- Based on observed RTT and bandwidth

- Generally leave auto-tuning enabled

- Manual tuning for special cases (high BDP, etc.)

7.3 Connection Scalability

Handling many connections:

File descriptor limits:

$ ulimit -n # Soft limit

$ ulimit -Hn # Hard limit

Raise in /etc/security/limits.conf:

* soft nofile 65535

* hard nofile 65535

Memory per connection:

- Socket structure: ~2 KB

- Send buffer: 16 KB - 4 MB

- Receive buffer: 4 KB - 6 MB

10,000 connections × 200 KB average = 2 GB memory

Event handling efficiency:

select(): O(n) per call, limited to 1024 fds

poll(): O(n) per call, no fd limit

epoll(): O(1) per event, O(n) setup, scalable

For high connection counts: use epoll (Linux), kqueue (BSD)

7.4 Latency Optimization

Sources of network latency:

1. Serialization delay: packet_size / bandwidth

1500 bytes / 1 Gbps = 12 μs

2. Propagation delay: distance / speed_of_light

Coast to coast US ≈ 40 ms

3. Queuing delay: Waiting in router/switch buffers

Variable, depends on congestion

4. Processing delay: Router/host packet processing

Usually negligible (~1 μs per hop)

Optimization strategies:

Reduce round trips:

- Connection pooling (reuse connections)

- TCP Fast Open (data in SYN)

- HTTP/2 multiplexing (one connection, many requests)

Reduce processing:

- Zero-copy where possible

- Kernel bypass (DPDK, io_uring)

- Jumbo frames (reduce packet count)

Reduce queuing:

- ECN (Explicit Congestion Notification)

- BBR congestion control

- QoS prioritization

7.5 Zero-Copy Techniques

Avoiding memory copies for high throughput:

Traditional send path:

User buffer → Kernel socket buffer → NIC DMA buffer → Wire

(2 copies minimum)

sendfile() - File to socket without user space:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ // Send file directly to socket │

│ sendfile(socket_fd, file_fd, &offset, count); │

│ │

│ File → Page cache → NIC DMA (with scatter-gather) │

│ Avoids: user buffer entirely! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

splice() - Move data between file descriptors:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ // Create pipe for zero-copy transfer │

│ int pipefd[2]; │

│ pipe(pipefd); │

│ │

│ // Move from socket to pipe │

│ splice(socket_in, NULL, pipefd[1], NULL, len, 0); │

│ │

│ // Move from pipe to file │

│ splice(pipefd[0], NULL, file_fd, NULL, len, 0); │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

MSG_ZEROCOPY for sends:

int one = 1;

setsockopt(sock, SOL_SOCKET, SO_ZEROCOPY, &one, sizeof(one));

send(sock, buf, len, MSG_ZEROCOPY);

// Kernel uses page pinning, notifies via error queue when done

When zero-copy helps:

- Large data transfers (MB+)

- High bandwidth links

- CPU-bound scenarios

When it doesn't help:

- Small messages (overhead > savings)

- Already memory-bound

- Latency-critical (may add delay)

8. Kernel Bypass and High Performance

When the kernel isn’t fast enough.

8.1 The Kernel Overhead Problem

Traditional network path:

NIC → DMA to kernel buffer → Interrupt → softirq processing →

Protocol processing → Copy to user buffer → Wake application

Overhead sources:

1. Interrupts: 5-15 μs each

2. Context switches: 1-10 μs

3. Memory copies: Bandwidth limited

4. System calls: ~100 ns each

5. Protocol processing: CPU time

For 10-100 Gbps: Kernel can't keep up!

8.2 DPDK: Data Plane Development Kit

DPDK approach:

User space Kernel space

┌──────────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ DPDK Application │ │ (bypassed) │

│ ┌──────────────┐ │ │ │

│ │ Poll Mode │ │ │ │

│ │ Driver │ │ │ │

│ └──────┬───────┘ │ │ │

└──────────┼───────────┘ └──────────────────┘

│ Direct access via huge pages

▼

┌──────────┐

│ NIC │

└──────────┘

Benefits:

- Zero kernel involvement

- No interrupts (busy polling)

- No memory copies (zero-copy)

- Millions of packets per second per core

Costs:

- Dedicated cores (100% CPU polling)

- Must implement protocols

- Lose kernel features (iptables, etc.)

- Complex programming model

8.3 io_uring for Networking

io_uring: Async I/O with kernel involvement

Submission Queue Completion Queue

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ Entry 0 │ │ Result 0 │

│ Entry 1 │ ───────► │ Result 1 │

│ Entry 2 │ Kernel │ Result 2 │

└─────────────┘ process └─────────────┘

Advantages for networking:

- Batched system calls (fewer context switches)

- Zero-copy send/receive

- Registered buffers (avoid allocation)

- Linked operations (chains of I/O)

// Submit multiple operations at once

io_uring_prep_recv(sqe1, sock1, buf1, len1, 0);

io_uring_prep_recv(sqe2, sock2, buf2, len2, 0);

io_uring_prep_send(sqe3, sock3, buf3, len3, 0);

io_uring_submit(&ring); // One syscall for three operations

8.4 XDP: eXpress Data Path

XDP: eBPF programs at NIC driver level

Packet arrives at NIC:

│

▼

┌───────────────────────┐

│ XDP Program (eBPF) │

│ │

│ Decision: │

│ - XDP_DROP │ ← Drop packet (fastest)

│ - XDP_PASS │ ← Normal kernel processing

│ - XDP_TX │ ← Bounce back out same NIC

│ - XDP_REDIRECT │ ← Send to different NIC/CPU

└───────────────────────┘

│

(if PASS)

▼

Normal stack

Use cases:

- DDoS mitigation (drop bad packets early)

- Load balancing

- Packet filtering

- Fast forwarding

Performance: Millions of packets per second

9. Observability and Debugging

Tools for understanding network behavior.

9.1 Socket Statistics

# Connection state summary

ss -s

# Total: 1024 (kernel 0)

# TCP: 500 (estab 400, closed 50, orphaned 10, timewait 30)

# All TCP connections with details

ss -tan

# State Recv-Q Send-Q Local:Port Peer:Port

# ESTAB 0 0 10.0.0.1:443 10.0.0.2:54321

# Show socket memory usage

ss -tm

# Includes: skmem:(r,rb,t,tb,f,w,o,bl,d)

# r: receive queue, t: send queue, etc.

# Filter by state

ss -tan state established '( dport = :443 )'

9.2 Network Statistics

# Interface statistics

ip -s link show eth0

# RX: bytes packets errors dropped

# TX: bytes packets errors dropped

# Protocol statistics

netstat -s

# IP, TCP, UDP, ICMP statistics

# Detailed TCP stats

cat /proc/net/tcp

# Or parsed: ss --info

# Real-time monitoring

sar -n DEV 1 # Per-interface

sar -n TCP 1 # TCP stats

9.3 Packet Capture

# tcpdump: Command-line capture

tcpdump -i eth0 port 80

tcpdump -i any tcp and host 192.168.1.1

tcpdump -w capture.pcap # Save to file

# Wireshark: GUI analysis

wireshark capture.pcap

# tshark: Wireshark CLI

tshark -i eth0 -f "port 443"

# BPF-based tracing

tcpdump 'tcp[tcpflags] & (tcp-syn) != 0' # SYN packets

9.4 Connection Tracing

# strace for socket operations

strace -e network ./app

# Shows: socket, bind, connect, send, recv, etc.

# bpftrace for kernel events

bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:tcp:tcp_retransmit_skb {

printf("Retransmit: %s:%d\n",

ntop(args->saddr), args->dport);

}'

# ss for real-time connection info

watch -n1 'ss -tan | grep ESTAB'

# conntrack for NAT tracking

conntrack -L

# Shows all tracked connections through NAT

9.5 Performance Profiling

Identifying network bottlenecks:

Bandwidth testing:

iperf3 -s # Server

iperf3 -c server_ip -t 30 # Client, 30 second test

Results show:

- Throughput (Mbps or Gbps)

- Retransmits (TCP reliability issues)

- CPU usage (processing bottleneck)

Latency measurement:

ping -c 100 host # Basic RTT

mtr host # Traceroute with statistics

hping3 -S -p 80 host # TCP-based latency

Connection timing breakdown:

curl -w "@timing.txt" https://example.com -o /dev/null

timing.txt:

time_namelookup: %{time_namelookup}s

time_connect: %{time_connect}s

time_appconnect: %{time_appconnect}s (TLS)

time_pretransfer: %{time_pretransfer}s

time_starttransfer: %{time_starttransfer}s (first byte)

time_total: %{time_total}s

Flame graphs for network code:

perf record -g ./network_app

perf script | stackcollapse.pl | flamegraph.pl > flame.svg

# Shows where CPU time goes in network processing

10. Summary and Best Practices

Key concepts and practical guidance.

10.1 Core Concepts Review

Socket fundamentals:

✓ Sockets are file descriptors with network operations

✓ TCP provides reliable, ordered, connection-oriented streams

✓ UDP provides unreliable, unordered, connectionless datagrams

TCP mechanics:

✓ Three-way handshake establishes connection

✓ Sequence numbers enable ordering and reliability

✓ Flow control prevents receiver overload

✓ Congestion control prevents network overload

Performance factors:

✓ Bandwidth-delay product determines buffer needs

✓ RTT affects throughput (must wait for ACKs)

✓ Connection reuse avoids handshake overhead

✓ Kernel bypass for extreme performance

10.2 Practical Guidelines

For application developers:

1. Use connection pooling

- Reuse connections when possible

- Avoid setup/teardown overhead

2. Set TCP_NODELAY for interactive protocols

- Avoids Nagle delay for small messages

- Essential for request-response patterns

3. Handle partial reads and writes

- read() may return less than requested

- Loop until complete or EOF

4. Use non-blocking I/O with event loops

- Scales to many connections

- epoll on Linux, kqueue on BSD

5. Set appropriate timeouts

- Connection timeout

- Read/write timeouts

- Keepalive for idle connections

For system administrators:

1. Monitor connection states

- Many TIME_WAIT = rapid connection churn

- Many SYN_RECV = possible SYN flood

2. Tune buffer sizes for high BDP

- Increase tcp_rmem/tcp_wmem max

- Let auto-tuning work

3. Choose appropriate congestion control

- BBR for high latency links

- CUBIC for general use

10.3 Debugging Checklist

When investigating network issues:

□ Check connection state (ss -tan)

□ Verify routing (ip route get <dest>)

□ Test connectivity (ping, traceroute)

□ Check for packet loss (netstat -s | grep retrans)

□ Verify DNS resolution (dig, nslookup)

□ Capture packets (tcpdump) if needed

□ Check firewall rules (iptables -L)

□ Monitor bandwidth utilization

□ Check for buffer overflows (netstat -s)

□ Review application logs for timeouts

□ Examine socket options and buffer sizes

□ Profile CPU usage during network operations

□ Check for connection leaks (increasing fd count)

□ Verify MTU settings match across path

□ Test with different congestion control algorithms

10.4 Security Considerations

Network security fundamentals:

Socket-level protection:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Bind to specific interfaces: │

│ - INADDR_LOOPBACK for local-only services │

│ - Specific IP for multi-homed hosts │

│ │

│ Set socket options: │

│ - SO_REUSEADDR carefully (can mask issues) │

│ - TCP_DEFER_ACCEPT (delay accept until data) │

│ │

│ Validate client addresses: │

│ - Check source IP/port in accept() │

│ - Implement connection rate limiting │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Common attack vectors:

SYN Flood:

- Attacker sends many SYNs, never completes handshake

- Fills SYN queue, prevents legitimate connections

- Mitigation: SYN cookies, increase backlog, rate limiting

TCP Reset Attacks:

- Inject RST packets to close connections

- Requires guessing sequence numbers

- Mitigation: Randomized ISN, TCP-AO authentication

Connection Hijacking:

- Predict sequence numbers to inject data

- Modern TCP uses random ISN to prevent

- Mitigation: TLS for application-layer security

Slow Read/Slowloris:

- Attacker reads data very slowly

- Ties up server resources

- Mitigation: Timeouts, connection limits

Kernel hardening:

sysctl net.ipv4.tcp_syncookies=1 # SYN flood protection

sysctl net.ipv4.tcp_max_syn_backlog=4096 # Larger SYN queue

sysctl net.core.somaxconn=4096 # Larger accept queue

Network programming bridges the gap between application logic and the physical reality of data transmission across wires and through the air. From the elegant abstraction of sockets through the intricate state machines of TCP to the raw speed of kernel bypass techniques, the network stack represents decades of engineering refinement. Understanding these internals empowers you to build efficient networked applications, diagnose mysterious connectivity problems, and optimize for the specific characteristics of your network environment. Whether you’re building real-time systems demanding microsecond latencies or web services handling millions of connections, the principles of the TCP/IP stack inform every packet that crosses the wire.