System Calls: The Gateway Between User Space and Kernel

An in-depth exploration of how applications communicate with the operating system kernel through system calls. Learn about the syscall interface, context switching, and how modern OSes balance security with performance.

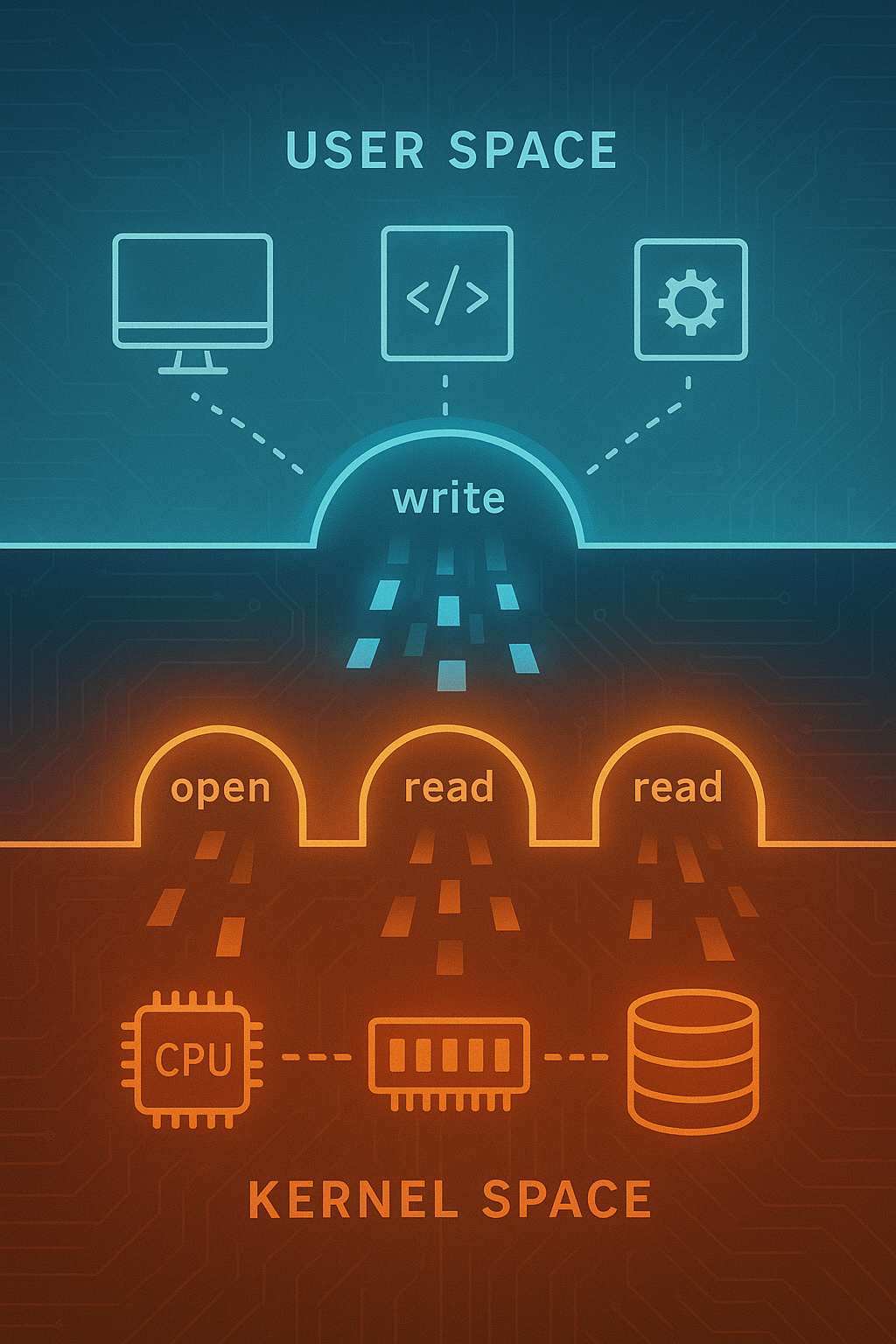

Every time your program opens a file, allocates memory, or sends a network packet, it crosses an invisible boundary. User programs cannot directly access hardware or kernel data structures—they must ask the operating system to do it for them through system calls. Understanding this interface is fundamental to systems programming and helps explain performance characteristics, security boundaries, and the design of operating systems themselves.

1. The User-Kernel Boundary

Modern operating systems divide the world into two privilege levels.

1.1 Why the Separation Exists

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Space │

│ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐ │

│ │ App A │ │ App B │ │ App C │ Ring 3 │

│ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ └────┬────┘ (Unprivileged)

│ │ │ │ │

├───────┼────────────┼────────────┼────────────────────┤

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ System Call Interface │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ Kernel Space │

│ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │

│ │ Process │ │ Memory │ │ File │ Ring 0 │

│ │ Manager │ │ Manager │ │ System │ (Privileged)

│ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Hardware Abstraction │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The separation provides several critical guarantees:

- Isolation: One misbehaving program cannot crash the system

- Security: Programs cannot read each other’s memory

- Resource management: The kernel arbitrates access to shared resources

- Hardware abstraction: Programs don’t need to know hardware details

1.2 Hardware Support for Privilege Levels

x86 processors provide four privilege rings, but most OSes use only two:

Ring 0: Kernel mode (supervisor mode)

- Full access to all CPU instructions

- Direct hardware access

- Can modify page tables

- Can disable interrupts

Ring 3: User mode

- Restricted instruction set

- Cannot access I/O ports directly

- Cannot modify system registers

- Memory access controlled by page tables

ARM uses a similar model with Exception Levels (EL0-EL3).

1.3 What Triggers a Privilege Level Change

User → Kernel transitions:

1. System calls (intentional)

2. Exceptions (divide by zero, page fault)

3. Interrupts (timer, I/O completion)

Kernel → User transitions:

1. Return from system call

2. Return from exception handler

3. Return from interrupt handler

4. Starting a new process

2. Anatomy of a System Call

Let’s trace what happens when you call write().

2.1 The Journey of write()

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

const char *msg = "Hello, kernel!\n";

write(1, msg, 15); // fd=1 is stdout

return 0;

}

The journey from this simple call to actual I/O involves many steps.

2.2 Libc Wrapper Functions

The C library provides wrapper functions that set up the system call:

// Simplified glibc write() implementation concept

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count) {

// Set up registers with syscall number and arguments

// On x86-64 Linux:

// RAX = __NR_write (syscall number 1)

// RDI = fd

// RSI = buf

// RDX = count

long result;

asm volatile (

"syscall"

: "=a" (result)

: "a" (__NR_write), "D" (fd), "S" (buf), "d" (count)

: "rcx", "r11", "memory"

);

if (result < 0) {

errno = -result;

return -1;

}

return result;

}

2.3 The SYSCALL Instruction

On modern x86-64, the syscall instruction is the gateway:

; Before syscall:

; RAX = system call number

; RDI, RSI, RDX, R10, R8, R9 = arguments 1-6

syscall

; The CPU atomically:

; 1. Saves RIP to RCX (return address)

; 2. Saves RFLAGS to R11

; 3. Loads new RIP from MSR_LSTAR (kernel entry point)

; 4. Loads new CS and SS (kernel segments)

; 5. Clears certain RFLAGS bits

; 6. Switches to Ring 0

2.4 Kernel Entry Point

The kernel’s syscall entry handler takes over:

// Simplified Linux syscall entry (arch/x86/entry/entry_64.S concepts)

ENTRY(entry_SYSCALL_64)

// Save user stack pointer

swapgs // Switch to kernel GS base

movq %rsp, PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_tss_rw + TSS_sp2)

movq PER_CPU_VAR(cpu_current_top_of_stack), %rsp

// Create stack frame with saved registers

pushq $__USER_DS // user SS

pushq PER_CPU_VAR(...) // user RSP

pushq %r11 // saved RFLAGS

pushq $__USER_CS // user CS

pushq %rcx // user RIP (return address)

// Save more registers for syscall arguments

pushq %rdi

pushq %rsi

pushq %rdx

...

// Call the actual syscall handler

movq %rax, %rdi // syscall number

call do_syscall_64

// Restore and return

...

sysretq // Return to user space

2.5 Syscall Dispatch Table

The kernel looks up the handler in a table:

// Simplified syscall table concept

typedef asmlinkage long (*sys_call_ptr_t)(

unsigned long, unsigned long, unsigned long,

unsigned long, unsigned long, unsigned long);

const sys_call_ptr_t sys_call_table[] = {

[0] = sys_read,

[1] = sys_write,

[2] = sys_open,

[3] = sys_close,

// ... hundreds more

[435] = sys_clone3, // As of Linux 5.x

};

asmlinkage long do_syscall_64(unsigned long nr, ...) {

if (nr < NR_syscalls) {

return sys_call_table[nr](arg1, arg2, arg3, arg4, arg5, arg6);

}

return -ENOSYS; // Invalid syscall number

}

2.6 The Actual write() Implementation

// Simplified sys_write (fs/read_write.c concepts)

SYSCALL_DEFINE3(write, unsigned int, fd, const char __user *, buf,

size_t, count)

{

struct fd f = fdget_pos(fd);

if (!f.file)

return -EBADF;

// Verify user pointer is actually in user space

if (!access_ok(buf, count))

return -EFAULT;

loff_t pos = file_pos_read(f.file);

ssize_t ret = vfs_write(f.file, buf, count, &pos);

file_pos_write(f.file, pos);

fdput_pos(f);

return ret;

}

3. System Call Categories

Linux provides hundreds of system calls organized by function.

3.1 Process Management

// Process creation and control

pid_t fork(void); // Create child process

pid_t vfork(void); // Create child, share memory until exec

int execve(const char *path, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

void _exit(int status); // Terminate process

pid_t wait4(pid_t pid, int *status, int options, struct rusage *rusage);

// Process information

pid_t getpid(void); // Get process ID

pid_t getppid(void); // Get parent process ID

uid_t getuid(void); // Get user ID

int setuid(uid_t uid); // Set user ID (privileged)

3.2 File Operations

// Basic file I/O

int open(const char *path, int flags, mode_t mode);

int close(int fd);

ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);

off_t lseek(int fd, off_t offset, int whence);

// Advanced file operations

int dup(int oldfd);

int dup2(int oldfd, int newfd);

int fcntl(int fd, int cmd, ...);

int ioctl(int fd, unsigned long request, ...);

ssize_t pread(int fd, void *buf, size_t count, off_t offset);

ssize_t pwrite(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count, off_t offset);

3.3 Memory Management

// Memory mapping

void *mmap(void *addr, size_t length, int prot, int flags,

int fd, off_t offset);

int munmap(void *addr, size_t length);

int mprotect(void *addr, size_t len, int prot);

int madvise(void *addr, size_t length, int advice);

// Heap management (brk is low-level; malloc uses mmap)

int brk(void *addr);

void *sbrk(intptr_t increment);

3.4 Networking

// Socket creation and connection

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);

int bind(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

int listen(int sockfd, int backlog);

int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen);

int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

// Data transfer

ssize_t send(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags);

ssize_t recv(int sockfd, void *buf, size_t len, int flags);

ssize_t sendto(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags,

const struct sockaddr *dest_addr, socklen_t addrlen);

ssize_t recvfrom(int sockfd, void *buf, size_t len, int flags,

struct sockaddr *src_addr, socklen_t *addrlen);

3.5 Synchronization and IPC

// Futex (fast userspace mutex)

int futex(int *uaddr, int futex_op, int val, ...);

// Signals

int kill(pid_t pid, int sig);

int sigaction(int signum, const struct sigaction *act,

struct sigaction *oldact);

int sigprocmask(int how, const sigset_t *set, sigset_t *oldset);

// Pipes

int pipe(int pipefd[2]);

int pipe2(int pipefd[2], int flags);

// Shared memory

int shmget(key_t key, size_t size, int shmflg);

void *shmat(int shmid, const void *shmaddr, int shmflg);

int shmdt(const void *shmaddr);

4. System Call Performance

System calls are expensive compared to regular function calls.

4.1 The Cost Breakdown

Regular function call: ~1-5 nanoseconds

System call: ~100-1000+ nanoseconds

Cost components:

┌────────────────────────────────────┬──────────────┐

│ Component │ Approx. Cost │

├────────────────────────────────────┼──────────────┤

│ syscall/sysret instructions │ 50-100 ns │

│ Kernel entry/exit code │ 20-50 ns │

│ TLB and cache effects │ 20-100 ns │

│ Context save/restore │ 10-30 ns │

│ Security checks (KPTI, etc.) │ 50-200 ns │

│ Actual work (varies by syscall) │ varies │

└────────────────────────────────────┴──────────────┘

4.2 Measuring System Call Overhead

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

int main() {

struct timespec start, end;

const int iterations = 1000000;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

syscall(SYS_getpid); // Minimal syscall

}

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

double elapsed = (end.tv_sec - start.tv_sec) * 1e9 +

(end.tv_nsec - start.tv_nsec);

printf("Average syscall time: %.2f ns\n", elapsed / iterations);

return 0;

}

Typical results on modern x86-64:

- Without mitigations: ~150-200 ns

- With Spectre/Meltdown mitigations: ~300-700 ns

4.3 Reducing System Call Overhead

Several techniques minimize syscall cost:

Batching Operations

// Bad: Many small writes

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

write(fd, &data[i], 1); // 1000 syscalls

}

// Good: One large write

write(fd, data, 1000); // 1 syscall

// Better: Use buffered I/O

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

fputc(data[i], file); // Buffered, few actual syscalls

}

fflush(file);

Vectored I/O

// Instead of multiple write() calls:

struct iovec iov[3] = {

{ .iov_base = header, .iov_len = header_len },

{ .iov_base = body, .iov_len = body_len },

{ .iov_base = footer, .iov_len = footer_len }

};

writev(fd, iov, 3); // Single syscall for multiple buffers

Memory-Mapped Files

// Instead of read/write syscalls:

void *map = mmap(NULL, file_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

// Direct memory access - no syscalls for data access

memcpy(map + offset, data, len);

// Sync when needed

msync(map, file_size, MS_SYNC);

5. The vDSO: Syscalls Without Privilege Transition

Some “system calls” don’t actually enter the kernel.

5.1 What is the vDSO?

vDSO = virtual Dynamic Shared Object

A small shared library mapped by the kernel into every process:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Process Address Space │

├─────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0x7fff... Stack │

│ ... │

│ 0x7ffd... vDSO (kernel-provided) │ ← Special kernel-mapped page

│ ... │

│ 0x7f00... Shared libraries │

│ ... │

│ 0x0040... Program text │

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

5.2 vDSO Functions

// These can be called without entering kernel:

#include <time.h>

// gettimeofday - reads kernel-maintained time data

int gettimeofday(struct timeval *tv, struct timezone *tz);

// clock_gettime - high-resolution clock

int clock_gettime(clockid_t clk_id, struct timespec *tp);

// getcpu - which CPU am I running on?

int getcpu(unsigned *cpu, unsigned *node, void *unused);

5.3 How vDSO Works

Traditional syscall path:

User code → syscall instruction → Kernel → Return

vDSO path:

User code → vDSO function → Read shared memory → Return

(No privilege transition!)

The kernel updates shared pages that vDSO functions read:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ vDSO Data Page (read-only to user) │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ current_time: 1639425367.123456789 │

│ timezone: UTC-5 │

│ cpu_features: AVX2, SSE4.2 │

│ ... │

└────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Kernel updates this page on timer interrupts

5.4 Performance Difference

// Benchmark: clock_gettime via syscall vs vDSO

#include <time.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

// Force actual syscall (bypass vDSO)

void syscall_clock_gettime(struct timespec *ts) {

syscall(SYS_clock_gettime, CLOCK_MONOTONIC, ts);

}

// Normal call (uses vDSO)

void vdso_clock_gettime(struct timespec *ts) {

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, ts);

}

// Results on typical x86-64:

// vDSO: ~20-30 ns

// Syscall: ~200-400 ns

// Difference: 10-20x faster!

6. io_uring: Asynchronous System Calls

Linux 5.1 introduced io_uring for high-performance async I/O.

6.1 The Problem with Traditional Async I/O

// Traditional approaches have issues:

// 1. select/poll - O(n) scanning, limited scalability

fd_set readfds;

select(nfds, &readfds, NULL, NULL, &timeout);

// 2. epoll - better, but still one syscall per batch

int n = epoll_wait(epfd, events, max_events, timeout);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

read(events[i].data.fd, buf, size); // More syscalls!

}

// 3. aio - complex API, poor performance for many use cases

io_submit(ctx, nr, iocbs);

io_getevents(ctx, min_nr, nr, events, timeout);

6.2 io_uring Architecture

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Space │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Application │ │

│ │ 1. Add entries to Submission Queue │ │

│ │ 2. Check Completion Queue for results │ │

│ └──────────────┬──────────────────┬───────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ ┌────────▼────────┐ ┌──────▼───────┐ │

│ │ Submission Queue │ │ Completion │ │

│ │ (SQ) - Ring │ │ Queue (CQ) │ │

│ │ Buffer │ │ Ring Buffer │ │

│ └────────┬─────────┘ └──────▲───────┘ │

├─────────────────┼──────────────────┼────────────────┤

│ │ Shared Memory │ │

│ ▼ │ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Kernel I/O Thread │ │

│ │ - Polls SQ for new requests │ │

│ │ - Processes I/O operations │ │

│ │ - Posts completions to CQ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ Kernel Space │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

6.3 Basic io_uring Usage

#include <liburing.h>

int main() {

struct io_uring ring;

// Initialize ring with 256 entries

io_uring_queue_init(256, &ring, 0);

// Prepare a read operation

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(&ring);

io_uring_prep_read(sqe, fd, buf, size, offset);

sqe->user_data = 42; // Identifier for completion

// Submit (may not need syscall with SQPOLL)

io_uring_submit(&ring);

// Wait for completion

struct io_uring_cqe *cqe;

io_uring_wait_cqe(&ring, &cqe);

// Process result

if (cqe->res >= 0) {

printf("Read %d bytes\n", cqe->res);

}

io_uring_cqe_seen(&ring, cqe);

io_uring_queue_exit(&ring);

return 0;

}

6.4 Zero-Copy Potential

With IORING_SETUP_SQPOLL, the kernel polls the submission queue:

struct io_uring_params params = {

.flags = IORING_SETUP_SQPOLL,

.sq_thread_idle = 10000 // Keep polling for 10ms after idle

};

io_uring_queue_init_params(256, &ring, ¶ms);

// Now submissions may not require ANY syscalls

// Kernel thread constantly polls the shared ring

7. System Call Interception and Tracing

Understanding how to observe and intercept syscalls is valuable for debugging and security.

7.1 strace: The Classic Tool

# Trace all syscalls of a program

strace ./program

# Trace specific syscalls

strace -e trace=open,read,write ./program

# Trace with timing

strace -T ./program

# Trace child processes too

strace -f ./program

# Example output:

# openat(AT_FDCWD, "/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY) = 3 <0.000015>

# read(3, "root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash\n"..., 4096) = 2381 <0.000010>

# close(3) = 0 <0.000006>

7.2 How strace Works: ptrace

#include <sys/ptrace.h>

int main() {

pid_t child = fork();

if (child == 0) {

// Child: allow parent to trace us

ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, 0, NULL, NULL);

execl("/bin/ls", "ls", NULL);

} else {

// Parent: trace child's syscalls

int status;

while (1) {

wait(&status);

if (WIFEXITED(status)) break;

// Read syscall number from child's registers

struct user_regs_struct regs;

ptrace(PTRACE_GETREGS, child, NULL, ®s);

printf("Syscall: %lld\n", regs.orig_rax);

// Continue to next syscall

ptrace(PTRACE_SYSCALL, child, NULL, NULL);

}

}

return 0;

}

7.3 eBPF for System Call Tracing

Modern Linux uses eBPF for efficient tracing:

// BPF program attached to syscall entry

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_openat")

int trace_openat(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter *ctx) {

char filename[256];

bpf_probe_read_user_str(filename, sizeof(filename),

(void *)ctx->args[1]);

bpf_printk("openat: %s\n", filename);

return 0;

}

eBPF advantages:

- Runs in kernel, minimal overhead

- Safe: verified before loading

- Can aggregate data in-kernel

- No context switches for tracing

7.4 Seccomp: Syscall Filtering

Restrict which syscalls a process can make:

#include <seccomp.h>

int main() {

scmp_filter_ctx ctx = seccomp_init(SCMP_ACT_KILL); // Default: kill

// Allow specific syscalls

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(read), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(write), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit), 0);

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit_group), 0);

// Activate filter

seccomp_load(ctx);

// Now any other syscall will terminate the process

write(1, "Hello\n", 6); // OK

open("/etc/passwd", 0); // KILLED!

}

Used extensively by:

- Container runtimes (Docker, containerd)

- Browsers (Chrome sandbox)

- systemd services

8. System Calls Across Operating Systems

Different OSes have different syscall conventions.

8.1 Linux vs macOS vs Windows

┌────────────────┬─────────────────┬─────────────────┬─────────────────┐

│ Aspect │ Linux │ macOS │ Windows │

├────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ Instruction │ syscall │ syscall │ syscall │

│ (x86-64) │ │ │ │

├────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ Number in │ RAX │ RAX │ RAX │

│ register │ │ (+ 0x2000000) │ │

├────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ Arguments │ RDI, RSI, RDX, │ RDI, RSI, RDX, │ RCX, RDX, R8, │

│ │ R10, R8, R9 │ R10, R8, R9 │ R9 + stack │

├────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ Stable ABI? │ Yes │ No (use libSystem)│ No (use ntdll)│

├────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ Documented? │ Yes │ No │ Partially │

└────────────────┴─────────────────┴─────────────────┴─────────────────┘

8.2 The Stable ABI Question

Linux guarantees syscall stability:

// This will work on any Linux kernel >= the version that introduced it

syscall(SYS_write, 1, "Hello", 5);

macOS and Windows do NOT:

// macOS: syscall numbers change between versions!

// Always use libSystem.dylib functions

// Windows: syscall numbers change between builds!

// Always use ntdll.dll exports

8.3 BSD Syscall Compatibility

Linux can run some BSD syscalls:

// FreeBSD syscall numbers differ from Linux

// But some compatibility exists through emulation layers

// Linux supports different syscall ABIs:

personality(PER_BSD); // Switch to BSD syscall numbering

9. Implementing a Minimal System Call

Understanding by building.

9.1 Adding a Custom Syscall to Linux

// 1. Define the syscall in kernel source

// kernel/sys.c

SYSCALL_DEFINE1(hello, const char __user *, name)

{

char kname[64];

if (copy_from_user(kname, name, sizeof(kname)))

return -EFAULT;

kname[sizeof(kname) - 1] = '\0';

printk(KERN_INFO "Hello, %s!\n", kname);

return 0;

}

// 2. Add to syscall table

// arch/x86/entry/syscalls/syscall_64.tbl

// 500 common hello sys_hello

// 3. Add prototype

// include/linux/syscalls.h

asmlinkage long sys_hello(const char __user *name);

9.2 Calling the Custom Syscall

#include <sys/syscall.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define SYS_hello 500

int main() {

long result = syscall(SYS_hello, "World");

printf("syscall returned: %ld\n", result);

return 0;

}

// Check kernel log:

// dmesg | tail

// [12345.678] Hello, World!

10. Security Implications of System Calls

System calls are the attack surface between user space and kernel.

10.1 Kernel Vulnerabilities

Attack vectors through syscalls:

1. Buffer overflows in argument handling

2. Race conditions (TOCTOU)

3. Integer overflows in size calculations

4. Use-after-free in object management

5. Information leaks through uninitialized memory

10.2 TOCTOU (Time-of-Check to Time-of-Use)

// Vulnerable pattern:

if (access("/tmp/file", W_OK) == 0) {

// Attacker changes /tmp/file to symlink here!

fd = open("/tmp/file", O_WRONLY);

write(fd, data, len); // Writes to wrong file!

}

// Safer pattern (check and use atomically):

fd = open("/tmp/file", O_WRONLY);

if (fd >= 0) {

// Now we have the actual file

fstat(fd, &st); // Verify it's what we expect

write(fd, data, len);

}

10.3 Spectre and Meltdown Mitigations

Post-2018 mitigations add syscall overhead:

KPTI (Kernel Page Table Isolation):

- Separate page tables for user/kernel

- TLB flush on every transition

- Cost: ~100-400 ns per syscall

Retpoline:

- Prevents speculative execution attacks

- Replaces indirect branches

- Cost: varies by workload

IBRS/STIBP:

- Hardware speculation barriers

- Cost: ~50-100 ns per syscall

10.4 Measuring Mitigation Impact

# Check active mitigations

cat /sys/devices/system/cpu/vulnerabilities/*

# Disable for testing (NOT for production!)

# Boot with: mitigations=off

# Benchmark comparison:

# With mitigations: ~400 ns per getpid()

# Without: ~100 ns per getpid()

11. Real-World Syscall Patterns

11.1 The Database Write Path

Application: INSERT INTO table VALUES (...)

write() path through syscalls:

1. write(fd, data, len) → Add to page cache

2. fsync(fd) → Flush to disk (durability)

└─ Actually triggers:

- Multiple bio submissions

- Disk controller commands

- Wait for completion interrupt

Optimization: O_DIRECT + io_uring for bypassing page cache

11.2 The Web Server Accept Loop

// Classic accept loop (one syscall per connection)

while (1) {

int client = accept(listen_fd, &addr, &addrlen);

// Handle client...

}

// Optimized with io_uring (batch accepts)

for (int i = 0; i < batch_size; i++) {

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(&ring);

io_uring_prep_accept(sqe, listen_fd, &addr, &addrlen, 0);

}

io_uring_submit(&ring);

// Process completions in batches

11.3 Container Startup

Container creation syscalls:

1. clone(CLONE_NEWPID | CLONE_NEWNET | ...) → New namespaces

2. pivot_root(new_root, put_old) → Change filesystem root

3. mount("proc", "/proc", "proc", ...) → Mount /proc

4. unshare(CLONE_NEWUSER) → User namespace

5. prctl(PR_SET_SECCOMP, ...) → Syscall filtering

6. execve("/init", ...) → Start container process

12. Debugging Syscall Issues

12.1 Common Error Codes

// Syscall errors are returned as negative numbers in kernel

// libc converts to -1 return with errno set

EPERM (1) // Operation not permitted

ENOENT (2) // No such file or directory

ESRCH (3) // No such process

EINTR (4) // Interrupted system call

EIO (5) // I/O error

ENOMEM (12) // Out of memory

EACCES (13) // Permission denied

EFAULT (14) // Bad address

EBUSY (16) // Device or resource busy

EEXIST (17) // File exists

EINVAL (22) // Invalid argument

EMFILE (24) // Too many open files

EAGAIN (11) // Try again (also EWOULDBLOCK)

12.2 Debugging Techniques

# Trace specific error-returning syscalls

strace -e fault=open:retval=-2 ./program

# Get syscall statistics

strace -c ./program

# % time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

# 45.23 0.012345 12 1000 10 read

# 32.10 0.008765 8 1000 0 write

# Trace only failed syscalls

strace -Z ./program

12.3 Performance Debugging

# perf for syscall overhead

perf stat -e syscalls:sys_enter_write ./program

# Flamegraph of syscall time

perf record -g ./program

perf script | stackcollapse-perf.pl | flamegraph.pl > flame.svg

13. Advanced System Call Topics

13.1 Restartable System Calls

When a signal arrives during a syscall, the behavior depends on the SA_RESTART flag:

#include <signal.h>

void handler(int sig) {

// Signal handler

}

int main() {

struct sigaction sa;

sa.sa_handler = handler;

sa.sa_flags = SA_RESTART; // Auto-restart interrupted syscalls

sigaction(SIGUSR1, &sa, NULL);

// With SA_RESTART: read() resumes after signal

// Without: read() returns -1 with errno = EINTR

char buf[1024];

ssize_t n = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

if (n < 0 && errno == EINTR) {

// Handle interruption manually

}

}

Common pattern for handling EINTR:

ssize_t safe_read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count) {

ssize_t n;

do {

n = read(fd, buf, count);

} while (n < 0 && errno == EINTR);

return n;

}

13.2 System Call Wrappers and Versioning

The kernel maintains compatibility through versioned syscalls:

// Original stat

int stat(const char *path, struct stat *buf);

// Extended for large files

int stat64(const char *path, struct stat64 *buf);

// Modern: uses AT_ flags for flexibility

int fstatat(int dirfd, const char *path, struct stat *buf, int flags);

// Newest: handles time with nanoseconds

int statx(int dirfd, const char *path, int flags,

unsigned int mask, struct statx *buf);

glibc handles the translation:

// User calls stat()

// glibc chooses appropriate syscall based on:

// - Kernel version

// - File size support needed

// - Architecture

13.3 System Calls for Container Namespaces

Linux namespaces isolate resources through syscalls:

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <sched.h>

#include <sys/mount.h>

int main() {

// Create new namespaces

unshare(CLONE_NEWPID | // New PID namespace

CLONE_NEWNET | // New network namespace

CLONE_NEWNS | // New mount namespace

CLONE_NEWUTS | // New hostname namespace

CLONE_NEWIPC); // New IPC namespace

// Fork to activate PID namespace

if (fork() == 0) {

// Child is PID 1 in new namespace

// Set new hostname

sethostname("container", 9);

// Mount private proc

mount("proc", "/proc", "proc", 0, NULL);

// Execute container init

execl("/bin/sh", "sh", NULL);

}

wait(NULL);

return 0;

}

13.4 Memory Protection Syscalls

Fine-grained memory control:

#include <sys/mman.h>

int main() {

// Allocate executable memory for JIT

void *jit_mem = mmap(NULL, 4096,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

// Write machine code

unsigned char code[] = {

0xb8, 0x2a, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // mov eax, 42

0xc3 // ret

};

memcpy(jit_mem, code, sizeof(code));

// Make executable (and remove write for security)

mprotect(jit_mem, 4096, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC);

// Execute

int (*func)(void) = jit_mem;

printf("Result: %d\n", func()); // Prints 42

munmap(jit_mem, 4096);

return 0;

}

13.5 File Descriptor Passing

Unix domain sockets can pass file descriptors between processes:

// Sender process

void send_fd(int unix_socket, int fd_to_send) {

struct msghdr msg = {0};

struct cmsghdr *cmsg;

char buf[CMSG_SPACE(sizeof(int))];

msg.msg_control = buf;

msg.msg_controllen = sizeof(buf);

cmsg = CMSG_FIRSTHDR(&msg);

cmsg->cmsg_level = SOL_SOCKET;

cmsg->cmsg_type = SCM_RIGHTS;

cmsg->cmsg_len = CMSG_LEN(sizeof(int));

memcpy(CMSG_DATA(cmsg), &fd_to_send, sizeof(int));

sendmsg(unix_socket, &msg, 0);

}

// Receiver process

int receive_fd(int unix_socket) {

struct msghdr msg = {0};

char buf[CMSG_SPACE(sizeof(int))];

int received_fd;

msg.msg_control = buf;

msg.msg_controllen = sizeof(buf);

recvmsg(unix_socket, &msg, 0);

struct cmsghdr *cmsg = CMSG_FIRSTHDR(&msg);

memcpy(&received_fd, CMSG_DATA(cmsg), sizeof(int));

return received_fd; // Now valid in this process!

}

This mechanism powers:

- Container runtimes (passing network sockets)

- systemd socket activation

- Web servers graceful restarts

14. Historical Evolution of System Calls

14.1 The Unix Heritage

1969-1971: Original UNIX (PDP-7, PDP-11)

- ~20 system calls

- Simple interface: open, read, write, close

- fork() for process creation

- exec() for program execution

1979: Version 7 UNIX

- ~50 system calls

- Network support beginning

- Still fits on a few pages

1983: 4.2BSD

- ~150 system calls

- Full networking (Berkeley sockets)

- New IPC mechanisms

1991: Linux 0.01

- ~100 system calls (mostly POSIX)

- Started on i386

2023: Linux 6.x

- ~450 system calls

- Multiple architectures

- io_uring, BPF, namespaces, cgroups

14.2 Notable Syscall Additions Over Time

Classic UNIX:

fork, exec, wait, exit Process control

open, read, write, close, seek File I/O

pipe, dup IPC

BSD additions:

socket, bind, listen, accept Networking

connect, send, recv

select I/O multiplexing

mmap Memory mapping

Linux innovations:

clone (1996) Flexible process/thread creation

epoll (2002) Scalable I/O multiplexing

inotify (2005) File system events

signalfd, timerfd, eventfd Unified fd interface

perf_event_open (2009) Performance monitoring

io_uring (2019) Async I/O revolution

clone3 (2019) Extensible process creation

14.3 Deprecated and Removed Syscalls

// These syscalls are obsolete but kept for compatibility:

// Old signal handling (use sigaction instead)

signal(SIGINT, handler); // Unreliable semantics

// Old wait variants (use waitpid/wait4)

wait3(&status, options, &rusage);

// Old networking (use socket API)

// The streams-based TLI interface

// Removed in recent kernels:

// uselib() - load shared library (security issues)

// query_module() - replaced by /sys filesystem

15. Syscall Performance Optimization Case Studies

15.1 Redis: Minimizing Syscall Overhead

Redis design principles for syscall efficiency:

1. Single-threaded event loop

- One epoll_wait() covers all clients

- No thread synchronization overhead

2. Pipeline support

- Multiple commands in one read()

- Multiple responses in one write()

3. Memory-mapped persistence

- RDB snapshots: fork() + write()

- AOF: write() + fdatasync() batching

4. Lazy deletion

- unlink() is cheap (immediate)

- Actual deletion is background

15.2 Nginx: Accept Queue Optimization

// Nginx uses multiple approaches:

// 1. Accept multiple connections per epoll wake

int events = epoll_wait(epfd, event_list, MAX_EVENTS, -1);

for (int i = 0; i < events; i++) {

while ((client = accept4(listen_fd, &addr, &len,

SOCK_NONBLOCK)) >= 0) {

handle_new_connection(client);

}

}

// 2. SO_REUSEPORT for kernel load balancing

int opt = 1;

setsockopt(fd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEPORT, &opt, sizeof(opt));

// Each worker has its own accept queue

// 3. TCP_DEFER_ACCEPT

setsockopt(fd, IPPROTO_TCP, TCP_DEFER_ACCEPT, &timeout, sizeof(timeout));

// Don't wake until data arrives

15.3 Database fsync() Strategies

Different durability vs. performance tradeoffs:

PostgreSQL:

- fsync() after each transaction commit (default)

- Option: synchronous_commit = off for speed

- Group commit: batch multiple transactions

MySQL InnoDB:

- innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit = 1 (safe)

- innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit = 2 (OS buffer)

- innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit = 0 (dangerous)

Modern approach with io_uring:

- Async fdatasync() calls

- Batch multiple syncs

- Continue processing while waiting

15.4 The Kernel Bypass Movement

For extreme performance, bypass the kernel entirely:

DPDK (Data Plane Development Kit):

- User-space network driver

- No syscalls for packet I/O

- Poll mode for minimum latency

- Used in: routers, load balancers, firewalls

SPDK (Storage Performance Development Kit):

- User-space NVMe driver

- Direct device access via UIO/VFIO

- No kernel file system overhead

- Used in: high-performance storage

Tradeoffs:

+ Latency: <1 μs vs 10+ μs with kernel

+ Throughput: millions of ops/sec

- Lose kernel protections

- Dedicated CPU cores required

- Complex deployment

16. Writing Syscall-Efficient Code

16.1 Batching Guidelines

// Bad: One syscall per small operation

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

write(fd, &records[i], sizeof(Record)); // 1000 syscalls

}

// Better: Batch into larger writes

write(fd, records, sizeof(Record) * 1000); // 1 syscall

// Best: Use writev for non-contiguous data

struct iovec iov[1000];

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

iov[i].iov_base = &records[i];

iov[i].iov_len = sizeof(Record);

}

writev(fd, iov, 1000); // 1 syscall

16.2 Avoiding Unnecessary Syscalls

// Bad: Check file existence then open

if (access(path, F_OK) == 0) {

fd = open(path, O_RDONLY); // 2 syscalls + race condition

}

// Good: Just try to open

fd = open(path, O_RDONLY); // 1 syscall

if (fd < 0 && errno == ENOENT) {

// File doesn't exist

}

// Bad: Get time multiple times

struct timeval tv1, tv2;

gettimeofday(&tv1, NULL);

// ... work ...

gettimeofday(&tv2, NULL); // 2 vDSO calls

// Okay for vDSO, but for real syscalls, cache when possible

time_t now = time(NULL); // Cache and reuse

16.3 Choosing the Right Abstraction

// For files: consider mmap vs read/write

// mmap wins for: random access, read-mostly, large files

// read/write wins for: sequential access, small files, write-heavy

// For networking: consider the I/O model

// Blocking: simple code, limited scalability

// Non-blocking + epoll: scalable, complex

// io_uring: highest performance, newest API

// For IPC: consider the mechanism

// Pipes: simple, unidirectional

// Unix sockets: bidirectional, fd passing

// Shared memory: zero-copy, needs synchronization

// Futex: efficient mutex/condition variable

17. Summary

System calls are the fundamental interface between user applications and the operating system kernel. Key concepts we’ve covered include:

The boundary:

- User space runs at Ring 3 (unprivileged)

- Kernel space runs at Ring 0 (privileged)

- Hardware enforces the separation

The mechanism:

syscallinstruction triggers privilege transition- Kernel validates arguments and performs operation

sysretreturns to user space

Performance considerations:

- Syscalls cost hundreds of nanoseconds

- Batch operations when possible

- Use vDSO for time-related calls

- Consider io_uring for high-throughput I/O

Security aspects:

- Syscalls are the kernel attack surface

- seccomp filters restrict available syscalls

- Spectre/Meltdown mitigations add overhead

Observability:

- strace for tracing syscalls

- eBPF for efficient in-kernel tracing

- perf for performance analysis

Understanding system calls helps you write more efficient programs, debug mysterious performance issues, and appreciate the sophisticated machinery that makes modern operating systems work. Every printf(), every network connection, every file access ultimately flows through this narrow but critical interface between your code and the kernel.