TLS, PKI, and Secure Protocols: How Encrypted Web Traffic Works

A deep technical guide to TLS, certificate validation, key exchange, record protection, modern cipher suites, TLS 1.3, QUIC, and practical deployment best practices for secure networked applications.

Encrypted network connections are the foundation of modern secure applications. TLS (Transport Layer Security) protects confidentiality, integrity, and — when properly used — authenticity for traffic between clients and servers. Behind the simple “https” URL there are layers of protocol design, public-key cryptography, symmetric ciphers, certificate chains and revocation systems, ephemeral key exchanges, and subtle deployment pitfalls. This post explores TLS in depth: the record protocol, handshakes (with a focus on TLS 1.3), certificate validation and PKI, cipher suites and AEAD, performance considerations, QUIC integration, operational security, and testing and hardening advice.

1. Security goals and threat model

Before diving into protocols, clarify what TLS is designed to protect and against what threats.

Primary security goals:

- Confidentiality: Prevent eavesdroppers from reading plaintext.

- Integrity: Detect accidental or malicious modification of messages.

- Authenticity: Prove the identity of endpoints (server and optionally client).

Typical threat model:

- Passive eavesdropper: An adversary can read packets on the network but not modify them.

- Active man-in-the-middle (MITM): Adversary can inject, modify, or drop packets between client and server.

- Endpoint compromise is out-of-scope: If the server or client is fully compromised, TLS can’t protect application data from the host attacker.

TLS aims to provide confidentiality and integrity even across untrusted networks by establishing shared secrets authenticated by public-key cryptography.

2. Overview: TLS layers and handshake goals

Two major components:

- Handshake: Authenticated key exchange using public-key primitives to derive shared symmetric keys and negotiate parameters (cipher suite, extensions).

- Record protocol: Fragmentation, compression (deprecated), MAC/AEAD protection, and the sending/receiving of application data encrypted and authenticated using the negotiated keys.

Handshakes also provide identity verification via certificates — typically X.509 certificates backed by a PKI (certificate authorities) chain.

High-level goals of a TLS handshake:

- Negotiate protocol version and cipher suite.

- Perform an authenticated key exchange that establishes forward secrecy (prefer ephemeral Diffie-Hellman).

- Authenticate the server (and optionally the client) via certificates or pre-shared keys.

- Derive session keys for record protection and optionally session resumption.

3. Public-key primitives and ephemeral key exchange

Key exchange provides initial shared secrets. Early TLS used RSA key transport; modern secure deployments prefer Diffie-Hellman (DH) and elliptic curve DH (ECDHE) for forward secrecy.

3.1 RSA key transport (legacy)

- Client generates a random premaster secret, encrypts it with the server’s RSA public key from the certificate and sends it to the server.

- Server decrypts with private key, derives session keys.

Problems:

- No forward secrecy: If the server’s private key is compromised later, an attacker can decrypt recorded sessions.

- Vulnerable to some server-side implementation issues (e.g., Bleichenbacher oracle attacks) mitigated by modern libraries but still discouraged.

3.2 (EC)DHE: ephemeral Diffie-Hellman

- Client and server each generate ephemeral DH key pairs (ideally using secure curves: x25519 or P-256/SECP256R1) and compute a shared secret via the Diffie-Hellman operation.

- Because ephemeral keys are used per session, compromise of long-term server keys doesn’t allow decryption of prior sessions (forward secrecy).

Curve choice and implementation:

- Prefer X25519 (Curve25519) for fast, safe, and simple implementations.

- P-256 (secp256r1) is widely used and NIST-approved but careful constant-time implementation is necessary.

3.3 Authenticating the key exchange

- The server signs parameters (e.g., the ephemeral public key and context) with its long-term private key from its certificate. This binds the handshake to the server’s identity.

- Signed parameters prevent active MITM who do not possess the server’s private key from performing a fake handshake.

4. Certificates, PKI, and validation

Certificates provide identity. X.509 certificates are digitally signed assertions that link a public key to an identity (domain name, organization) and are typically issued by Certificate Authorities (CAs).

4.1 Certificate chain and validation steps

- Server sends certificate chain: server cert (leaf) followed by intermediate CA certs (if any), up to a root CA (optionally omitted).

- Client validates:

- Signature chain: verify each cert is signed by the next issuer, up to a trusted root.

- Validity period: check notBefore ≤ now ≤ notAfter.

- Purpose: key usage and extended key usage must allow TLS server authentication.

- Hostname verification: the certificate’s SAN (SubjectAltName) or CN matches the requested host.

- Revocation: check OCSP/CRL or use modern stapling mechanisms.

4.2 Certificate Authorities and trust stores

- Browsers/OS ship with root CA trust stores; trusting a root CA means trusting the CA to issue valid certificates.

- Risks: a compromised or mistaken CA can issue fraudulent certificates, enabling MITM attacks for any domain.

Mitigations & ecosystem improvements:

- Certificate Transparency (CT): Public logs of issued certificates enable detection of misissuance by owners.

- Short-lived certificates and automated issuance (ACME/Let’s Encrypt) reduce live windows for revoked keys.

- Multi-path validation and pinning are advanced mitigations but have operational complexities.

4.3 OCSP and stapling

- OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol) is used to check certificate revocation but suffers privacy and availability issues when clients query OCSP responders directly.

- OCSP stapling: Server periodically fetches OCSP response and staples it in the TLS handshake, preserving client privacy and reducing latency.

4.4 Certificate types & mutual TLS

- Server certificates: issued for hostnames (SANs), used by servers to authenticate to clients.

- Client certificates (mutual TLS): clients present certificates to authenticate themselves to servers — common in enterprise and service-to-service scenarios.

Mutual TLS requires careful key management and provisioning of client certificates.

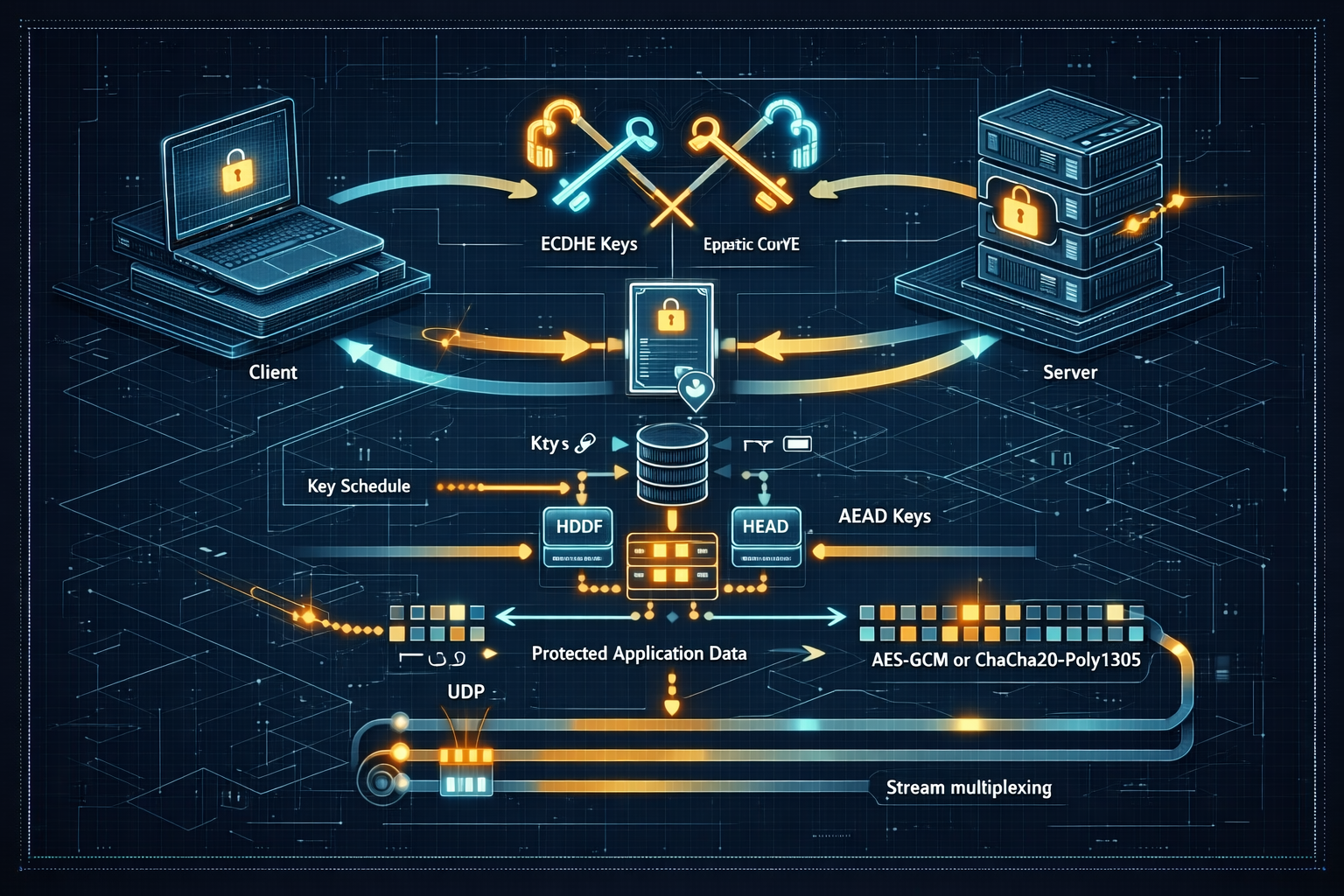

5. TLS 1.3: streamlined handshake and security improvements

TLS 1.3 (RFC 8446) simplifies and secures the handshake compared to TLS 1.2.

Key changes:

- Removed insecure and legacy algorithms (RSA key transport, static DH, SHA-1 MACs, MD5-based approaches).

- Handshake reduced: Full handshake typically completes in one RTT for key exchange and authentication; zero-RTT (0-RTT) resumption enables client data to be sent immediately when safe.

- All key exchanges use (EC)DHE for forward secrecy by default.

- Simplified record protection with AEAD (e.g., AES-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305) only.

- Early data (0-RTT) is supported for resumption but must be replayable and treated carefully.

5.1 1-RTT handshake (TLS 1.3 flow)

High-level flow:

- Client sends ClientHello (supported groups, cipher suites, extensions, and optionally pre-shared key identities for resumption).

- Server responds with ServerHello selecting parameters and sends its Certificate, CertificateVerify (signature over the handshake), and Finished messages.

- Client verifies certificates and signatures, sends its Finished message; both sides compute application traffic keys and start encrypted application data.

5.2 0-RTT resumption caveats

- 0-RTT allows client to send data immediately based on an earlier session’s PSK; the server may accept early data without replay-protection unless explicit anti-replay measures are in place.

- Only idempotent or carefully designed operations should be allowed in 0-RTT.

5.3 Key schedule and HKDF

- TLS 1.3 uses HKDF (HMAC-based Extract-and-Expand Key Derivation Function) to derive keys from shared secrets, mixing in handshake transcripts to avoid key reuse or cross-protocol attacks.

The HKDF-based key schedule ensures strong separation between handshake secrets, application keys, and resumption keys.

6. Record protocol and AEAD ciphers

TLS protects application data using symmetric encryption with authentication provided by MAC or, in modern TLS, AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) ciphers.

6.1 AEAD: AES-GCM and ChaCha20-Poly1305

- AES-GCM: High performance on hardware with AES-NI; requires unique nonces per key; misuse (nonce reuse) is catastrophic.

- ChaCha20-Poly1305: Software-friendly stream cipher + Poly1305 MAC; excellent performance on systems without AES acceleration.

Associated Data (AD): TLS records authenticate protocol metadata (sequence numbers, header fields) as AD ensuring integrity over both ciphertext and some unencrypted headers.

6.2 Nonce/IV management

- TLS uses per-record IVs derived from explicit nonce and implicit counters to ensure uniqueness.

- Implementations must carefully follow the standard to prevent nonce reuse or predictable IVs causing catastrophic compromises.

6.3 Record sizing, fragmentation, and TCP interactions

- TLS records may be fragmented; record size affects latency and throughput.

- Interaction with TCP: small writes cause Nagle/Delayed ACK interactions; use TCP_NODELAY for low-latency interactive protocols but batch writes where appropriate for efficiency.

7. Post-quantum considerations and algorithm agility

Quantum computers threaten certain public key schemes (RSA, ECDH) used in TLS key exchange and signatures. The practical response:

- Algorithm agility: TLS cipher suite negotiation and extensions allow swapping to new primitives when standardized.

- Hybrid key exchange: Combine classical (ECDHE) and post-quantum KEM (Key Encapsulation Mechanism) to obtain security even if one primitive is broken.

- Standardization: NIST PQC process selects candidate algorithms; IETF TLS working group explores integrating KEMs into TLS 1.3.

Operational realities: Post-quantum primitives often have larger keys or ciphertexts which affect handshake size and performance — plan for transition.

8. QUIC and TLS: moving TLS into transport

QUIC integrates TLS 1.3 handshake directly into the transport protocol, replacing TCP+TLS stacks with a single UDP-based protocol that handles encryption and multiplexing.

Advantages:

- 0-RTT and faster connection setup: QUIC reduces handshake latency by combining connection establishment and TLS handshake over UDP.

- Head-of-line elimination: QUIC implements multiplexed streams so that packet loss affects only the streams that referenced lost packets, avoiding TCP HOL blocking.

- Connection migration: QUIC supports client IP changes without a full reconnect via connection IDs.

Differences:

- QUIC encrypts most packet headers (spin bit aside) and uses a separate packet number space per encryption level.

- Deployment: QUIC requires kernel bypass or userland UDP stacks and adjustments to middleboxes—widely used now (HTTP/3).

9. Practical deployment, hardening, and performance tuning

9.1 Cipher suite selection and ordering

- Prefer TLS 1.3: simplifies choices and eliminates unsafe options.

- For TLS 1.2 compatibility: prefer ECDHE for forward secrecy and AEAD ciphers (AES-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305). Avoid RC4, MD5, SHA-1, export ciphers, or NULL suites.

9.2 Certificate provisioning and automation

- Use ACME/Let’s Encrypt for automated issuance and renewal.

- Ensure proper key sizes (2048+ bits for RSA, or better, ECDSA with P-256 or Ed25519 where supported).

- Automate OCSP stapling and monitor expiration to avoid outages.

9.3 Performance: session resumption and TLS overhead

- Session tickets and PSK resumption reduce handshake cost. Rotate and encrypt session tickets with server-side keys.

- TLS termination hardware and TLS offload can reduce CPU but may complicate end-to-end security and key management.

- Use HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 multiplexing to reduce connection churn and TLS handshakes per user session.

9.4 Logging, telemetry, and observability

- Log TLS versions and cipher suites negotiated, handshake failures, and certificate validation issues.

- Track handshake latency, session resumption rates, and 0-RTT usage to understand performance.

9.5 Hardening checklist

- Disable TLS 1.0/1.1 and weak ciphers. Enforce minimum TLS 1.2 or 1.3.

- Enable HSTS and, where applicable, HTTP Public Key Pinning replacement strategies (pinsets via Expect-CT or CT enforcement).

- Enforce certificate transparency monitoring and configure OCSP stapling.

- Rotate keys and TLS session ticket encryption keys periodically.

10. Testing: fuzzing, protocol compliance, and interoperability

Test using multiple vectors:

- Protocol conformance: Use test suites (e.g., OpenSSL testengines, BoringSSL test vectors) and interop testing across stacks.

- Fuzzing: Implement protocol fuzzers to test parsing of handshake messages and certificates.

- Security testing: Run TLS scanners (e.g., sslscan, testssl.sh, Qualys SSL Labs) and automated checks for cipher weaknesses.

11. Common pitfalls and attack patterns

- Misconfigured servers accepting older TLS versions or weak ciphers.

- Failure to validate certificate chains correctly, allowing MITM with self-signed certs.

- Improper session ticket key management leading to cross-tenant decryption.

- 0-RTT overuse leading to replay vulnerabilities for non-idempotent operations.

12. Observability and debugging checklist

When TLS connections fail or are slow:

□ Check client and server TLS version and negotiated cipher suite □ Inspect certificate chain and verify that intermediate certs are correctly served □ Monitor OCSP stapling and revocation response times □ Check handshake latency and whether full or resumed handshakes are happening □ Evaluate CPU usage and rate of ephemeral key operations (ECDHE) under load

13. Summary and practical recommendations

- Prefer TLS 1.3 and ephemeral (EC)DHE for forward secrecy.

- Use AEAD ciphers (AES-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305) and ensure proper nonce management.

- Automate certificate issuance and renewal; enable OCSP stapling.

- Plan for QUIC/HTTP/3 for improved performance and modern transport features.

- Continuously test and monitor (interoperability, security scans, CT logs) and be ready to adapt to post-quantum recommendations.

14. TLS handshake internals: messages and transcript protection

A more precise view of TLS 1.3 message flow clarifies how security is tied to the handshake transcript.

- ClientHello (CH): contains supported versions, supported_groups (curves), signature_algorithms, supported cipher suites, key_share (client’s ephemeral public key), supported extensions (ALPN, SNI, status_request for OCSP), PSK identities when resuming.

- ServerHello (SH): selects a version, cipher suite, and includes its key_share (server ephemeral public key) and selected extensions.

- EncryptedExtensions: server-specific app-level negotiated options (ALPN selection, etc.), encrypted under handshake keys.

- Certificate, CertificateVerify: server authenticates by sending its certificate and a signature over a transcript hash.

- Finished: both sides verify by sending MAC/HKDF-derived verify values; Finished binds transcript integrity to key material.

The transcript hash (e.g., SHA-256 over concatenated messages) is mixed into the HKDF key schedule at specific points. This design prevents key re-use and protects handshake integrity even if the transcript is exposed separately.

Example: verifying server identity with OpenSSL

A quick practical check from the command line to view server certificate and OCSP stapling (if present):

openssl s_client -connect example.com:443 -servername example.com -tls1_3 -status

Look for the certificate chain, the “OCSP response:” section (stapled response), and the negotiated cipher. Use -showcerts to dump chain and -alpn “h2,http/1.1” to request ALPN.

15. Certificate validation pitfalls and diagnostic tips

- Missing intermediate certificates: If the server fails to send intermediate CA certs, some clients may not build a chain to a trusted root and will reject the certificate. Always serve the full chain (leaf + intermediates).

- Wrong SANs: If SANs do not include the requested hostname, hostname verification fails.

- Expired or soon-to-expire certificates: Monitor expiration and renew at least a few days before expiry.

Diagnostic tips:

- Use openssl s_client -showcerts -connect host:443 to inspect the served chain.

- Use

curl --verbose --tlsv1.3 https://host/to observe ALPN negotiation and the cipher in use. - Use online scanners (Qualys SSL Labs) to get a full report.

16. Session resumption, tickets, and PSK lifecycle

Session tickets are opaque blobs issued by the server to allow resumption without server-side session storage. Important operational notes:

- Tickets should be encrypted and integrity-protected by a server-side key (often per-data-center key). Rotate ticket encryption keys regularly and provide grace periods for in-flight tickets.

- Ticket replay across different tenants (multi-tenant environments) can leak session context. Scope tickets appropriately and avoid cross-tenant use.

- For distributed systems, either use a shared rotation key or use a scheme where a central key management service signs/unwraps tickets.

PSK handshake flow (resumption): the client includes PSK identity in ClientHello; server validates and uses the PSK to derive session keys quickly, enabling 0-RTT when configured.

17. 0-RTT: design patterns, anti-replay, and safe usage

0-RTT allows sending application data in the first flight when resuming. Because early data is not forward-protected and may be replayed, apply strict rules:

- Restrict accepted 0-RTT operations to idempotent requests (GETs) or operations that server can safely deduplicate.

- Use server-side per-PSK replay caches that track nonces or use timestamps to limit replay windows.

- Document which endpoints are safe for 0-RTT and make clients explicit in what they can do in early data.

18. QUIC packet protection and packet number spaces

QUIC separates packet protection into levels (Initial, Handshake, 0-RTT, 1-RTT), each with separate keys and packet number spaces. Key facts:

- Initial packets are encrypted using keys derived from well-known, per-version constants and the client’s initial Destination Connection ID.

- The handshake completes and yields 1-RTT keys derived from TLS 1.3’s handshake secrets.

- QUIC encrypts most header fields (except some bits like the spin bit if enabled) to prevent passive observers from easy connection-level metrics.

Packet numbers in QUIC act like sequence numbers and are used for anti-replay and replay detection; they are encoded in a way that allows efficient length while preserving monotonic order.

19. Post-quantum hybrids: how to combine KEMs with ECDHE

A practical hybrid approach:

- Perform an ECDHE exchange to get classical shared secret S1.

- Perform a KEM encapsulation (post-quantum) yielding shared secret S2.

- Combine S = HKDF-Extract(S1 || S2) and continue the TLS key schedule.

This provides defense-in-depth: an attacker must break both primitives to recover S. Implementations must carefully handle different sizes and timings: PQ KEM ciphertexts and keys are often larger and affect Hello message sizes.

20. Implementation pitfalls and constant-time requirements

- Side channels: Private key operations (RSA, ECDSA, ECDH) must be constant-time to avoid leaking bits through timing. Use constant-time libraries and avoid branching on secret data.

- Randomness: Random number generation is critical. Use OS-provided CSPRNGs (e.g., getrandom on Linux or SecRandom on macOS) and verify entropy source at startup.

- Fingerprint/serialization differences: Different libraries may encode extensions or certificate order differently — interop testing is essential.

21. Performance microbenchmarks and realistic metrics

What to measure:

- Handshakes per second: measure CPU cost per full handshake (TLS 1.3 full) and PSK resumption throughput.

- Latency: measure time to first byte for various network RTTs and TCP/TLS interactions. QUIC/HTTP/3 often reduces tail latency.

- AEAD throughput: profile AES-GCM with and without AES-NI vs ChaCha20-Poly1305 in software-bound servers.

Example microbenchmark approach (Linux):

- Use a dedicated test client/server pair on isolated CPUs to measure baseline.

- Use tools like wrk2 or custom scripts to open and close many connections per second and record CPU utilization.

- Profile openssl speed for cryptographic primitives: openssl speed -evp aes-128-gcm

22. Operational runbook: certificate expiry or stapling failure

Immediate steps:

- Identify impacted hosts and affected clients (from logs).

- Verify current certificate chain and reachable OCSP responders using openssl s_client -status.

- If certificates expired: obtain emergency replacement via ACME (Let’s Encrypt) or from CA; if renewal automation failed, investigate the automation logs.

- If OCSP stapling failed: confirm server fetcher can contact the responder, and check server’s cron/task that fetches OCSP responses.

- During recovery, notify clients and route traffic to fallback endpoints if necessary.

23. Testing checklist for CI/CD and preproduction

- Automated integration tests: configure CI to validate TLS negotiation against a matrix of client-library-version pairs.

- Certificate renewal test: include a dry-run ACME renewal and test stapled OCSP responses retrieval.

- Performance regression tests: add handshake-per-second and AEAD throughput gates to CI.

- Fuzzing: schedule periodic fuzz runs against parsers (particularly certificate and extension parsers) to catch regressions.

24. References and further reading

- RFC 8446 — TLS 1.3

- RFC 8446 Appendix: Key schedule and HKDF usage

- QUIC RFCs (RFC 9000 et al.) and HTTP/3 (RFC 9114)

- TLS 1.3 walkthroughs (various modern TLS library docs)

- NIST PQC competition publications

Appendix: Common commands and snippets

Inspect server certificate and OCSP stapling:

openssl s_client -connect example.com:443 -servername example.com -tls1_3 -status

Check HTTP/3 with curl (if compiled with HTTP/3 support):

curl --http3 -v https://example.com/

Dump TLS handshake messages with Wireshark (beware of encrypted payloads) and use the TLS dissectors to inspect ClientHello and ServerHello content.

25. Example server configuration snippets

Nginx (modern TLS 1.3 config snippet):

server {

listen 443 ssl http2;

server_name example.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/certs/example.com.fullchain.pem; # cert + intermediates

ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private/example.com.key;

ssl_protocols TLSv1.3 TLSv1.2; # avoid older protocols

ssl_prefer_server_ciphers off;

ssl_ciphers 'TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384:TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256:TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256';

ssl_session_tickets on;

ssl_session_timeout 1d;

ssl_session_cache shared:SSL:50m;

ssl_stapling on;

ssl_stapling_verify on;

resolver 8.8.8.8 8.8.4.4 valid="300s;

resolver_timeout 5s;

}

Caddy (simpler, automated CA + OCSP stapling):

example.com {

tls you@example.com

encode gzip

reverse_proxy localhost:8080

}

Caddy handles ACME and OCSP stapling by default, which simplifies automation.

26. HKDF & key schedule (pseudo-code)

A short, conceptual HKDF snippet that mirrors TLS 1.3’s extract/expand steps (pseudocode):

# HKDF-Extract(salt, ikm) -> prk

prk = HMAC(salt, ikm)

# HKDF-Expand(prk, info, L) -> okm

okm = HKDF-Expand(prk, info, L)

# Example: combine shared secret with transcript hash

early_secret = HKDF-Extract(zero, "")

handshake_secret = HKDF-Extract(early_secret, shared_secret)

client_handshake_key = HKDF-Expand(handshake_secret, "c hs traffic", key_len)

server_handshake_key = HKDF-Expand(handshake_secret, "s hs traffic", key_len)

This isn’t a substitute for the RFC text but illustrates how secrets are mixed and labeled such that keys are context-specific.

27. Session ticket rotation pattern (example)

Servers should periodically roll the ticket encryption keys. A safe pattern:

- Keep two active keys: current and previous.

- Tickets encrypted with previous key are still accepted for a grace period.

- New tickets are encrypted with current key only.

- Rotate keys by generating a new key, atomically swapping it in as the current key, and scheduling the oldest key for retirement after the grace window.

Pseudocode outline:

current_key = load_current_key()

previous_key = load_previous_key()

new_ticket = encrypt_with(current_key, ticket_plaintext)

# On rotate:

previous_key = current_key

current_key = generate_new_key()

# After grace_period, delete previous_key

Centralized key management (KMS) or HSM-backed keys reduce risk of key sync errors in multi-node environments.

28. 0-RTT anti-replay sketch

A practical server anti-replay strategy for 0-RTT:

- Include an early-data identifier (EDID) in 0-RTT payloads.

- Server checks EDID against a deduplication store (e.g., Redis) with TTL equal to the replay window.

- If EDID exists, reject the request as a replay; otherwise, process and record EDID.

Caveats: The dedup store must be sufficiently available and fast; otherwise you risk blocking clients or accepting replays.

29. Post-quantum migration notes and MTU impact

Many PQ KEMs produce larger public keys and ciphertexts, which can bloat the ClientHello/ServerHello sizes and risk exceeding typical MTU values. Practical steps:

- Support TLS fragmentation and GREASE-like padding strategies to avoid middlebox issues.

- Prefer hybrid or post-quantum algorithms that minimize handshake growth during the early transition.

- Monitor real-world handshake sizes and adjust path MTU or Hello fragmentation settings as needed.

30. CI tests and automation examples

Add the following automated checks to CI pipelines:

- Validate that servers respond with TLS 1.3:

openssl s_client -tls1_3 -connect host:443 - Verify OCSP stapling:

openssl s_client -status -connect host:443 - Run a weekly test against external scanners (use an internal account of SSL Labs’ API or local testssl.sh batch runs) to detect regressions.

A sample GitHub Actions job snippet for TLS checks:

jobs:

tls-check:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Check TLS 1.3

run: |

openssl s_client -tls1_3 -connect example.com:443 -servername example.com -brief

- name: Check OCSP stapling

run: |

openssl s_client -status -connect example.com:443 -servername example.com

31. Closing thoughts

TLS and the surrounding ecosystem (PKI, OCSP, CT, QUIC) are complex but mature. The security of deployed systems depends as much on careful operational practices as on cryptographic choices. Keep software updated, automate certificate lifecycle tasks, monitor continuously and favor conservative deployment strategies (disable weak algorithms, enable stapling, and establish resumption and ticket rotation policies).

32. Certificate Transparency (CT) monitoring in practice

Certificate Transparency (CT) logs are append-only public logs of issued certificates. Domain owners should monitor CT logs for unexpected certificates to detect misissuance.

- Retrieval: Use public CT log APIs (e.g., Google/Cloudflare) or tools like

crt.shandcertstreamto detect newly issued certificates for your domain. - Verification: Look for Signed Certificate Timestamps (SCTs) embedded in certificates or stapled via OCSP. If a CA issues a certificate without CT inclusion where your policy requires CT, that can be a red flag.

Automation example: run a daily certstream listener that alerts on certificates containing your domain and pull CT log entries to verify the certificate fingerprints.

33. Incident post‑mortem (realistic, short)

Scenario: A regional intermediate CA used by a managed hosting provider expired without the hosting provider updating their served certificate chain. Clients that relied on the full chain failed to validate certificates, causing a partial outage for clients with strict validation.

Root cause: The server was configured with an intermediate chain that had an expiring intermediate; the automation that refreshed chains missed the intermediate update.

Remediation and lessons:

- Implement automated chain verification during certificate renewal; ensure

openssl verifysucceeds on the full served chain. - Monitor client-side error rates (validation failures) in production logs and set alerts.

- Maintain a small, tested fallback chain or have a rapid replacement certificate ready for emergency replacement.

34. TLS for IoT and resource-constrained devices

Considerations:

- Choose efficient cipher suites: ChaCha20-Poly1305 can be better than AES-GCM on devices without AES acceleration.

- Use session resumption aggressively to reduce handshake frequency and CPU cost.

- Consider raw DTLS for datagram transports with smaller stacks or use QUIC when feasible for modern stacks.

- Keep certificate chains short and use short-lived certs if automated provisioning is available to reduce risk from key compromise.

35. Side-channel mitigations and constant-time implementations

- Use vetted cryptographic libraries (e.g., BoringSSL, OpenSSL with side-channel mitigations, libsodium for ChaCha20/Poly1305).

- Keep libraries up to date for CPU-specific mitigations (e.g., for BEAST/ROBOT-style side channels or microarchitectural issues).

- Ensure constant-time arithmetic for private-key operations and prefer algorithms designed to be constant-time (X25519, Ed25519).

36. Structured TLS logging example

A structured log entry helps debugging and analytics. Example JSON for a TLS connection event:

{

"timestamp": "2025-12-21T12:34:56Z",

"peer": "198.51.100.12:52345",

"sni": "example.com",

"alpn": "h2",

"tls_version": "TLS1.3",

"cipher": "TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256",

"session_resumed": true,

"handshake_ms": 35,

"certificate_chain_valid": true,

"ocsp_stapled": true

}

Searching for unusual values (long handshake_ms, repeated validation failures, or deprecated ciphers) can point quickly to regressions.

37. Certificate pinning, Expect-CT, and practical tradeoffs

Certificate pinning (HPKP) once allowed clients to pin a CA fingerprint to a host, but HPKP proved brittle and is now deprecated in browsers. Safer alternatives:

- Expect-CT: instructs browsers to expect Certificate Transparency for your host. Example header:

Expect-CT: enforce, max-age=86400, report-uri="https://ct.example.com/report"

- Public Key Pinning Replacement: managed pinsets and CT monitoring performed by site owners reduce risk without pinning-related availability hazards.

Tradeoffs: overly aggressive pinning or misconfigured Expect-CT can cause availability incidents; prefer monitoring plus short-lived certs and emergency rotation plans.

38. QUIC adoption case study (practical rollout)

When a mid-sized web service migrated several key endpoints to QUIC/HTTP/3 they observed:

- 10–20% reduction in median TTFB (time-to-first-byte) for mobile clients due to fewer RTTs and connection aggregation.

- Reduced tail latency under moderate packet loss because multiplexing avoided head-of-line blocking.

Migration lessons:

- Start with non-critical traffic and monitor metrics closely (TTFB, error rates, handshake failures).

- Ensure load balancers and DDoS protections support UDP and don’t silently drop QUIC packets.

- Plan for dual-stack (TCP+TLS fallback) since some clients or networks may still block UDP.

39. Testing tools: TLS-Attacker, testssl.sh, and fuzzing setups

- testssl.sh: quick and effective TLS scanner. Example:

./testssl.sh example.comreports supported protocol versions, cipher suites, and common vulnerabilities. - TLS-Attacker / custom fuzz harnesses: used to test how a server tolerates malformed handshakes and extensions.

- Fuzz approach: focus on certificate parsing, extension parsing (SNI, ALPN), and maximal size messages (e.g., huge ClientHello with many extensions) which often reveal parsing bugs.

40. FAQ (concise answers)

Q: How do I ensure forward secrecy?

A: Use TLS 1.3 or ECDHE cipher suites, enable ephemeral key exchange, and avoid RSA key transport. Rotate keys and keep TLS libraries up to date.

Q: Do I need mutual TLS (mTLS)?

A: Use mTLS when you need strong client authentication (B2B APIs, service-to-service) and you can manage certificate provisioning. For public web apps, mTLS is rarely user-friendly.

Q: What about middleboxes that break TLS?

A: TLS 1.3 and QUIC reduce middlebox visibility; when middleboxes interfere, you may need to work with network operators or use HTTP-level fallbacks while monitoring for degraded client reachability.

Q: ChaCha20 or AES-GCM — which to choose?

A: Prefer AES-GCM when AES-NI is available and ChaCha20-Poly1305 when it isn’t. Support both and let clients pick; server-side benchmarks help decide defaults.

Q: How should I handle certificate revocation?

A: Use OCSP stapling, short-lived certificates, and monitor CT logs. Avoid relying on client-side OCSP fetches for availability reasons.

In closing, the best operational strategy combines modern cryptography (TLS 1.3, AEAD, ECDHE), automation (ACME, OCSP stapling, ticket rotation), and robust testing and observability. Focus on measurable goals (handshake latency, resumption rate, CT monitoring alerts) and plan for phased upgrades (QUIC rollout, PQ hybrid experiments) rather than big-bang migrations.

Further reading (brief annotated list)

- RFC 8446 — TLS 1.3: the canonical specification with the full key schedule and security considerations.

- QUIC RFCs (RFC 9000+): details of QUIC transport and how TLS is integrated into it.

- Certificate Transparency project docs and

crt.shfor real-world monitoring. - testssl.sh and TLS-Attacker project pages for testing and adversarial testing guidance.

- NIST PQC publications and candidate algorithm documentation for planning post-quantum transitions.

Actionable quick checklist (implement in the next sprint)

- Ensure TLS 1.3 is enabled and TLS 1.0/1.1 disabled across all endpoints.

- Enable OCSP stapling and monitor stapling failures.

- Add a CI job that runs

openssl s_client -tls1_3andtestssl.shagainst staging hosts nightly. - Implement automated ACME renewals with monitoring and alerts for failure.

- Rotate session ticket keys regularly and add rotation tests to automation.

- Start QUIC pilot on non-critical endpoints and monitor TTFB and tail latency.