Unicode and Character Encoding: From ASCII to UTF-8 and Beyond

A comprehensive guide to how computers represent text. Understand the evolution from ASCII through Unicode, the mechanics of UTF-8 encoding, and how to handle text correctly in modern software.

Text seems simple until you try to handle it correctly. A single question—“how many characters are in this string?"—can have multiple valid answers depending on what you mean by “character.” Understanding Unicode and character encoding is essential for any programmer working with internationalized text, file formats, network protocols, or databases.

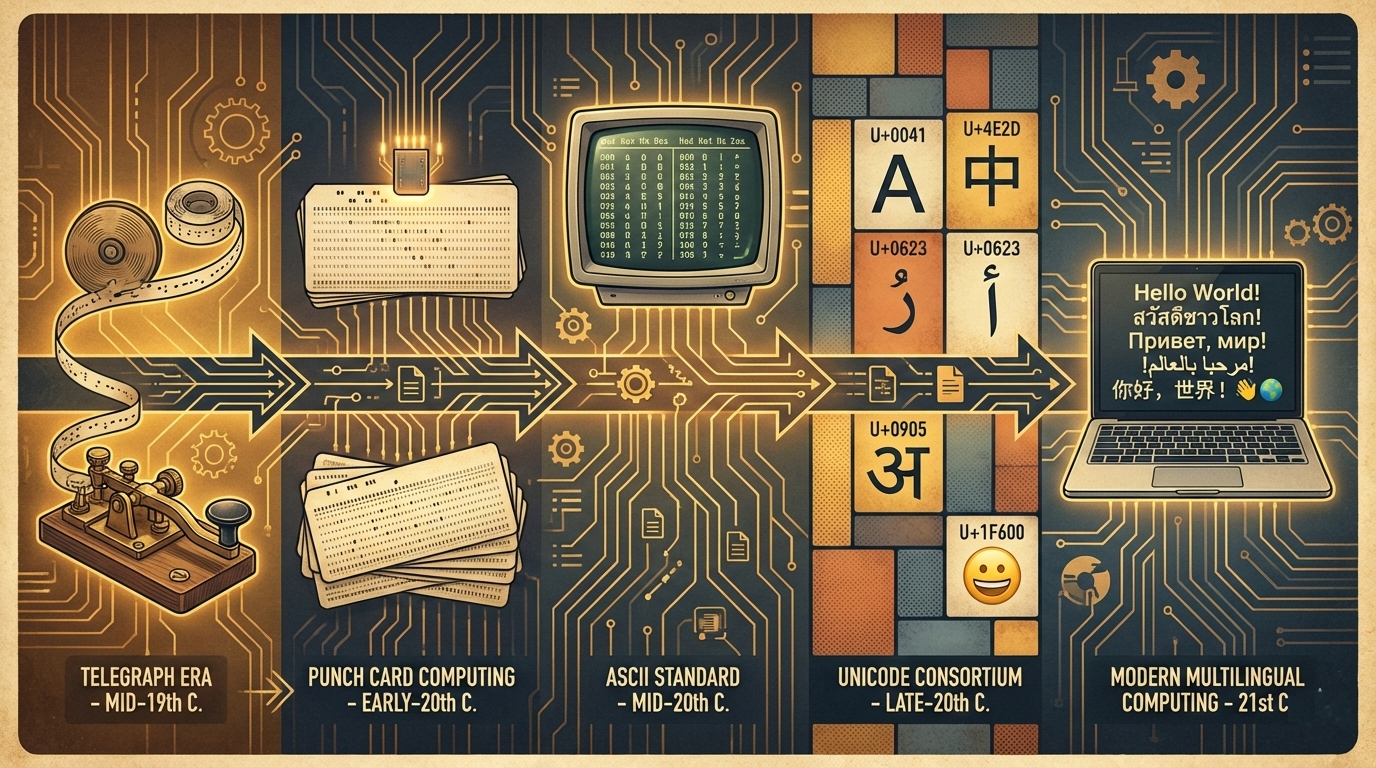

1. The History of Character Encoding

Before we can understand where we are, we need to know how we got here.

1.1 The Telegraph Era

Early electrical communication needed a code:

Morse Code (1840s):

A = .- B = -... C = -.-.

D = -.. E = . F = ..-.

...

Baudot Code (1870s):

- 5-bit encoding (32 possible codes)

- Used in teleprinters

- Shift codes to switch between letters and figures

1.2 ASCII: The Foundation

ASCII (1963): American Standard Code for Information Interchange

7-bit encoding = 128 possible characters

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 0-31 Control characters (NUL, TAB, LF, CR, ESC) │

│ 32-47 Punctuation and symbols (space, !, ", #...) │

│ 48-57 Digits 0-9 │

│ 58-64 More punctuation (:, ;, <, =, >, ?, @) │

│ 65-90 Uppercase A-Z │

│ 91-96 More punctuation ([, \, ], ^, _, `) │

│ 97-122 Lowercase a-z │

│ 123-127 More punctuation and DEL ({, |, }, ~, DEL) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key design decisions:

- Letters are contiguous (easy iteration)

- Uppercase and lowercase differ by 1 bit (bit 5)

- Digits have their value in low nibble (0x30-0x39)

1.3 The Extended ASCII Chaos

8-bit computers had 256 possible values, but only 128 used.

The "high ASCII" (128-255) became a free-for-all:

Code Page 437 (IBM PC, US):

- Box-drawing characters: ╔═╗║╚╝

- Math symbols: ±≥≤÷

- Some accented letters: é ñ

Code Page 850 (Western European):

- More accented letters: à é í ó ú ü

- Different box-drawing characters

Code Page 1251 (Windows Cyrillic):

- А Б В Г Д Е Ж for Russian

ISO 8859-1 (Latin-1):

- Western European: café, naïve, résumé

The problem: Same byte, different character!

0x80 = Ç (CP437) = € (CP1252) = А (CP1251)

1.4 Multi-Byte Encodings for Asian Languages

Asian languages need thousands of characters:

Shift-JIS (Japanese):

- Single byte for ASCII

- Double byte for Japanese characters

- Complex, overlapping ranges

GB2312 / GBK (Chinese):

- Similar double-byte scheme

- Different mapping

EUC-KR (Korean):

- Yet another double-byte scheme

Problems:

- Can't mix languages easily

- Detection is unreliable

- Many incompatible standards

2. Unicode: One Standard to Rule Them All

Unicode aims to assign a unique number to every character in every writing system.

2.1 The Unicode Consortium

Founded in 1991 by tech companies:

- Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Sun, and others

Goal: Universal character set

Current state (Unicode 15.1, 2023):

- 149,813 characters

- 161 scripts (alphabets, syllabaries, etc.)

- Emoji, symbols, historical scripts

- Still growing!

2.2 Code Points

A code point is a number assigned to a character.

Written as U+XXXX (hexadecimal):

U+0041 = A (Latin Capital Letter A)

U+03B1 = α (Greek Small Letter Alpha)

U+4E2D = 中 (CJK Ideograph, "middle/center")

U+1F600 = 😀 (Grinning Face emoji)

U+0000 to U+10FFFF = 1,114,112 possible code points

Not all code points are assigned:

- Many reserved for future use

- Some permanently unassigned (surrogates)

2.3 Unicode Planes

Unicode is divided into 17 "planes" of 65,536 code points each:

Plane 0: Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP)

U+0000 to U+FFFF

- Most common characters

- Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew

- CJK ideographs (Chinese, Japanese, Korean)

- Common symbols

Plane 1: Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP)

U+10000 to U+1FFFF

- Historic scripts

- Musical notation

- Emoji! (U+1F600 onwards)

Plane 2: Supplementary Ideographic Plane (SIP)

U+20000 to U+2FFFF

- Rare CJK characters

Planes 3-13: Mostly unassigned

Plane 14: Supplementary Special-purpose Plane

Planes 15-16: Private Use Areas

2.4 Properties and Categories

Every code point has properties:

General Category:

- Lu = Letter, uppercase (A, B, C)

- Ll = Letter, lowercase (a, b, c)

- Nd = Number, decimal digit (0-9)

- Zs = Separator, space

- Sm = Symbol, math (+, −, ×)

- So = Symbol, other (©, ®, emoji)

Other properties:

- Script (Latin, Cyrillic, Han)

- Bidirectional class (for RTL text)

- Canonical combining class

- Numeric value

3. Encodings: From Code Points to Bytes

A code point is abstract. Encodings convert them to actual bytes.

3.1 UTF-32: Simple but Wasteful

Every code point = 4 bytes (32 bits)

U+0041 (A) = 00 00 00 41

U+4E2D (中) = 00 00 4E 2D

U+1F600 (😀) = 00 01 F6 00

Pros:

- Simple: fixed width

- Random access: character N is at byte 4N

Cons:

- Wasteful: ASCII text is 4x larger

- Endianness: need to specify BE or LE

- Rarely used in practice

3.2 UTF-16: The Windows and Java Choice

Code points in BMP (U+0000-U+FFFF): 2 bytes

Code points above BMP: 4 bytes (surrogate pairs)

Surrogate pair encoding:

1. Subtract 0x10000 from code point

2. High 10 bits + 0xD800 = high surrogate (0xD800-0xDBFF)

3. Low 10 bits + 0xDC00 = low surrogate (0xDC00-0xDFFF)

Example: U+1F600 (😀)

1. 0x1F600 - 0x10000 = 0xF600

2. High 10 bits: 0x3D → 0xD83D

3. Low 10 bits: 0x200 → 0xDE00

4. Result: D8 3D DE 00 (UTF-16BE)

Pros:

- Efficient for Asian text (mostly 2 bytes)

- Native in Windows, Java, JavaScript

Cons:

- Variable width (2 or 4 bytes)

- Surrogate pairs are confusing

- Endianness issues (UTF-16LE vs UTF-16BE)

3.3 UTF-8: The Web Standard

Variable-width encoding: 1-4 bytes per code point

┌──────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Code Point Range │ Byte Sequence │

├──────────────────┼─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ U+0000-U+007F │ 0xxxxxxx │

│ U+0080-U+07FF │ 110xxxxx 10xxxxxx │

│ U+0800-U+FFFF │ 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx │

│ U+10000-U+10FFFF │ 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx │

└──────────────────┴─────────────────────────────────────┘

Example: U+4E2D (中)

Binary: 0100 1110 0010 1101

Template: 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

Result: 11100100 10111000 10101101 = E4 B8 AD

Example: U+1F600 (😀)

Binary: 0001 1111 0110 0000 0000

Template: 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

Result: 11110000 10011111 10011000 10000000 = F0 9F 98 80

3.4 Why UTF-8 Won

UTF-8 advantages:

✓ ASCII compatible (first 128 bytes are identical)

✓ No endianness issues (byte-oriented)

✓ Self-synchronizing (can find character boundaries)

✓ No embedded NUL bytes (except for U+0000)

✓ Compact for English/Latin text

✓ Safe for C strings and Unix paths

UTF-8 on the web (2024):

- 98%+ of websites use UTF-8

- HTML5 default encoding

- JSON specification requires UTF-8

3.5 Byte Order Mark (BOM)

BOM: A special code point U+FEFF at file start

UTF-8 BOM: EF BB BF

- Optional, often discouraged

- Can break Unix scripts (#!/bin/bash)

UTF-16 BOM:

- FE FF = UTF-16BE (big endian)

- FF FE = UTF-16LE (little endian)

UTF-32 BOM:

- 00 00 FE FF = UTF-32BE

- FF FE 00 00 = UTF-32LE

Common advice: Don't use BOM for UTF-8

4. Grapheme Clusters: What Users See

A “character” to a user isn’t always a single code point.

4.1 Combining Characters

Some characters are built from multiple code points:

é = U+0065 (e) + U+0301 (combining acute accent)

= 2 code points, 1 grapheme

ñ = U+006E (n) + U+0303 (combining tilde)

= 2 code points, 1 grapheme

क्षि (Hindi) = multiple code points for one syllable

The sequence of base character + combining marks

= Extended Grapheme Cluster

4.2 Precomposed vs Decomposed

Many accented characters have two representations:

NFC (Composed):

é = U+00E9 (Latin Small Letter E with Acute)

1 code point

NFD (Decomposed):

é = U+0065 U+0301 (e + combining acute)

2 code points

Both render identically!

But: strcmp("é", "é") might return non-zero

4.3 Emoji and ZWJ Sequences

Modern emoji can be multiple code points:

👨👩👧👦 (Family) =

U+1F468 (man) +

U+200D (ZWJ) +

U+1F469 (woman) +

U+200D (ZWJ) +

U+1F467 (girl) +

U+200D (ZWJ) +

U+1F466 (boy)

= 7 code points, 1 grapheme cluster

👋🏽 (Waving hand with skin tone) =

U+1F44B (waving hand) +

U+1F3FD (medium skin tone)

= 2 code points, 1 grapheme cluster

🏳️🌈 (Rainbow flag) =

U+1F3F3 (white flag) +

U+FE0F (variation selector) +

U+200D (ZWJ) +

U+1F308 (rainbow)

= 4 code points, 1 grapheme cluster

4.4 String Length: It’s Complicated

# Python example

text = "👨👩👧👦"

len(text) # 11 (Python 3 counts UTF-16 code units on Windows,

# or code points on other platforms)

len(text.encode('utf-8')) # 25 bytes

# What the user sees: 1 emoji

# To count grapheme clusters, you need a library

import grapheme

grapheme.length(text) # 1

5. Normalization

Making equivalent strings actually equal.

5.1 The Four Normalization Forms

NFD (Canonical Decomposition):

- Decompose characters to base + combining marks

- é → e + ◌́

NFC (Canonical Composition):

- Decompose, then recompose

- e + ◌́ → é

- Preferred for storage and interchange

NFKD (Compatibility Decomposition):

- Decompose, including compatibility equivalents

- fi → fi, ① → 1

NFKC (Compatibility Composition):

- Decompose (compatibility), then recompose

- Most aggressive normalization

5.2 When to Normalize

# Always normalize when comparing strings

import unicodedata

s1 = "café" # With precomposed é

s2 = "cafe\u0301" # With combining acute

s1 == s2 # False!

unicodedata.normalize('NFC', s1) == unicodedata.normalize('NFC', s2) # True

# Normalize on input, store normalized

def clean_input(text):

return unicodedata.normalize('NFC', text)

5.3 Security and Normalization

Homograph attacks use similar-looking characters:

аррӏе.com vs apple.com

↑ ↑

Cyrillic Latin

U+0430 (а, Cyrillic) looks like U+0061 (a, Latin)

U+0440 (р, Cyrillic) looks like U+0070 (p, Latin)

U+04CF (ӏ, Cyrillic) looks like U+006C (l, Latin)

Defense: IDN (Internationalized Domain Names) rules

- Restrict mixing scripts

- Show punycode for suspicious domains

6. Bidirectional Text

Some scripts are written right-to-left.

6.1 Right-to-Left Scripts

RTL scripts:

- Arabic: العربية

- Hebrew: עברית

- Persian (Farsi): فارسی

- Urdu: اردو

When RTL and LTR text mix:

"The word مرحبا means hello"

↑

This should render right-to-left

within the left-to-right sentence

6.2 The Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm

UAX #9 defines how to order characters for display.

Each character has a bidi class:

- L = Left-to-right (Latin letters)

- R = Right-to-left (Hebrew letters)

- AL = Arabic letter (special rules)

- EN = European number

- AN = Arabic number

- WS = Whitespace

- ON = Other neutral

The algorithm:

1. Split into paragraphs

2. Determine base direction

3. Resolve character types

4. Reorder for display

Result: Proper interleaving of LTR and RTL text

6.3 Bidi Overrides and Security

Explicit controls can change display order:

U+202E (RIGHT-TO-LEFT OVERRIDE)

Causes following text to display RTL

Security issue:

filename: myfile[U+202E]fdp.exe

displays: myfileexe.pdf

↑

Looks like PDF, is really EXE!

Defense: Filter or escape bidi controls

7. Common Encoding Problems

Real-world issues every programmer encounters.

7.1 Mojibake

Mojibake: Garbled text from encoding mismatch

Example:

Correct: Björk

Wrong: Björk (UTF-8 bytes interpreted as Latin-1)

"Björk" in UTF-8: 42 6A C3 B6 72 6B

↑↑

ö = C3 B6 in UTF-8

Interpreted as Latin-1:

C3 = Ã

B6 = ¶

Result: Björk

7.2 Double Encoding

Data encoded twice:

Original: "Café"

UTF-8 encoded: 43 61 66 C3 A9

Accidentally UTF-8 encoded again:

C3 → C3 83

A9 → C2 A9

Result bytes: 43 61 66 C3 83 C2 A9

Displayed: "Café"

Prevention:

- Know your encoding at each layer

- Don't encode already-encoded data

7.3 The Replacement Character

U+FFFD (�) indicates decoding errors

When a UTF-8 decoder encounters invalid bytes,

it substitutes U+FFFD for each bad sequence.

"Hello" with corruption: "He�o"

If you see � in your output:

1. Wrong encoding specified

2. Data corruption

3. Truncated multi-byte sequence

7.4 Database Encoding Issues

-- MySQL: Always specify UTF-8 correctly

CREATE TABLE users (

name VARCHAR(100) CHARACTER SET utf8mb4

) CHARACTER SET utf8mb4 COLLATE utf8mb4_unicode_ci;

-- Note: MySQL's "utf8" is NOT real UTF-8!

-- It only supports 3 bytes (no emoji)

-- Use "utf8mb4" for real UTF-8

-- PostgreSQL: Database encoding

CREATE DATABASE mydb WITH ENCODING 'UTF8';

7.5 File I/O Encoding

# Python: Always specify encoding explicitly

# WRONG (system default may vary)

with open('file.txt', 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

# RIGHT

with open('file.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

content = f.read()

# Handle encoding errors

with open('file.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8', errors='replace') as f:

content = f.read() # Bad bytes become U+FFFD

8. Programming Language Specifics

How different languages handle strings.

8.1 Python 3

# Strings are Unicode (sequences of code points)

s = "Hello 世界 🌍"

len(s) # 11 (code points, not bytes)

# Bytes are separate

b = s.encode('utf-8') # b'Hello \xe4\xb8\x96\xe7\x95\x8c \xf0\x9f\x8c\x8d'

len(b) # 18 bytes

# Decoding

text = b.decode('utf-8')

# Iteration is by code point

for char in "café":

print(repr(char)) # 'c', 'a', 'f', 'é'

8.2 JavaScript

// Strings are UTF-16 internally

const s = "Hello 🌍";

s.length; // 8 (UTF-16 code units, not characters!)

// 🌍 is a surrogate pair, counts as 2

"🌍".length; // 2

// Proper iteration with for...of

[..."🌍"].length; // 1

// Or use Array.from

Array.from("Hello 🌍").length; // 7

// Code point access

"🌍".codePointAt(0); // 127757 (0x1F30D)

String.fromCodePoint(127757); // "🌍"

8.3 Java

// Java strings are UTF-16

String s = "Hello 🌍";

s.length(); // 8 (code units)

s.codePointCount(0, s.length()); // 7 (code points)

// Iteration over code points

s.codePoints().forEach(cp ->

System.out.println(Character.toString(cp)));

// Converting to UTF-8 bytes

byte[] utf8 = s.getBytes(StandardCharsets.UTF_8);

8.4 Rust

// Rust strings are guaranteed valid UTF-8

let s = "Hello 🌍";

s.len(); // 11 bytes

s.chars().count(); // 7 code points

// Iteration options:

for c in s.chars() { // By code point

println!("{}", c);

}

for b in s.bytes() { // By byte

println!("{}", b);

}

// Grapheme clusters need external crate (unicode-segmentation)

use unicode_segmentation::UnicodeSegmentation;

s.graphemes(true).count();

8.5 Go

// Go strings are byte slices (often UTF-8)

s := "Hello 🌍"

len(s) // 11 bytes

utf8.RuneCountInString(s) // 7 runes (code points)

// Iteration with range gives runes

for i, r := range s {

fmt.Printf("%d: %c\n", i, r)

}

// Explicit rune conversion

runes := []rune(s)

len(runes) // 7

9. Best Practices

Guidelines for handling text correctly.

9.1 The Golden Rules

1. Know your encoding

- UTF-8 for interchange and storage

- Be explicit at every boundary (file, network, database)

2. Normalize consistently

- NFC for storage

- Normalize on input

3. Don't assume length

- Code points ≠ grapheme clusters

- Grapheme clusters ≠ display width

- Use proper libraries for text operations

4. Test with real data

- Include multi-byte characters

- Include emoji

- Include RTL text

- Include combining characters

9.2 Input Handling

# Validate and normalize input

import unicodedata

def sanitize_input(text):

# Normalize to NFC

text = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', text)

# Remove control characters (except newlines)

text = ''.join(

c for c in text

if unicodedata.category(c) != 'Cc' or c in '\n\r\t'

)

# Optionally filter zero-width characters

# (for security-sensitive contexts)

return text

9.3 String Comparison

import unicodedata

import locale

def compare_strings(a, b):

# Normalize both strings

a = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', a)

b = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', b)

# Simple equality

return a == b

def compare_strings_locale(a, b):

# Locale-aware comparison (for sorting)

return locale.strcoll(a, b)

# For case-insensitive comparison:

# Use casefold(), not lower()

"ß".lower() == "ss" # False

"ß".casefold() == "ss" # True

9.4 String Storage

Database:

- Use UTF-8 columns (utf8mb4 in MySQL)

- Consider collation for sorting

- Store normalized text

Files:

- Save as UTF-8 without BOM

- Use encoding declaration in source files

APIs:

- Specify Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

- Handle encoding errors gracefully

9.5 Display Considerations

# Width calculation for terminals

import unicodedata

def display_width(text):

"""Calculate display width in terminal columns."""

width = 0

for char in text:

# East Asian Width property

eaw = unicodedata.east_asian_width(char)

if eaw in ('F', 'W'): # Fullwidth or Wide

width += 2

else:

width += 1

return width

display_width("Hello") # 5

display_width("世界") # 4 (each CJK char is 2 columns)

10. Encoding Detection

When you don’t know the encoding, you have to guess.

10.1 Detection Heuristics

Order of confidence:

1. BOM present → Use indicated encoding

2. Declared in metadata (HTTP header, XML declaration)

3. All bytes < 128 → ASCII (subset of UTF-8)

4. Valid UTF-8 with multi-byte sequences → Probably UTF-8

5. Statistical analysis → Educated guess

UTF-8 validity check:

- No bytes 0xC0-0xC1 or 0xF5-0xFF

- All continuation bytes (10xxxxxx) follow start bytes

- Overlong encodings are invalid

10.2 Using Chardet

import chardet

# Detect encoding

raw_bytes = b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xe6\x96\x87'

result = chardet.detect(raw_bytes)

print(result)

# {'encoding': 'utf-8', 'confidence': 0.99, 'language': ''}

text = raw_bytes.decode(result['encoding'])

print(text) # 中文

10.3 The Limits of Detection

Detection can fail:

- Short samples lack statistical significance

- Some encodings are ambiguous

- Corruption can mislead detectors

Best practice:

- Try to obtain encoding metadata

- Default to UTF-8 (most common)

- Let users override if wrong

- Log encoding issues for debugging

11. Special Characters and Edge Cases

Characters that cause problems.

11.1 Invisible Characters

Zero-Width Characters:

- U+200B Zero Width Space

- U+200C Zero Width Non-Joiner

- U+200D Zero Width Joiner (emoji sequences)

- U+FEFF Byte Order Mark / Zero Width No-Break Space

Problems:

- Invisible in most displays

- Break string comparison

- Can bypass filters

- Security implications

Detection:

import re

has_zwc = bool(re.search(r'[\u200b-\u200d\ufeff]', text))

11.2 Null Bytes

U+0000 (NUL):

- String terminator in C

- Can truncate strings in many systems

- Security risk in file names

Prevention:

- Reject or strip null bytes from input

- Use length-prefixed strings internally

11.3 Newlines

Different platforms, different conventions:

Unix/Linux: LF (U+000A)

Windows: CRLF (U+000D U+000A)

Classic Mac: CR (U+000D)

Unicode also: NEL (U+0085), LS (U+2028), PS (U+2029)

Best practice:

- Normalize to LF internally

- Convert to platform convention on output

- Handle all variants on input

11.4 Whitespace Varieties

Many different "space" characters:

U+0020 Space (regular)

U+00A0 No-Break Space (HTML )

U+2002 En Space

U+2003 Em Space

U+2009 Thin Space

U+3000 Ideographic Space (CJK)

Trimming should consider all whitespace:

import re

text = re.sub(r'[\s\u00a0\u2000-\u200a\u3000]+', ' ', text)

12. Internationalization and Localization

Building software for a global audience.

12.1 Beyond Encoding: Cultural Considerations

Text handling involves more than encoding:

Sorting (Collation):

- German: ä sorts with a

- Swedish: ä sorts after z

- Case sensitivity varies by language

Number formatting:

- US: 1,234,567.89

- Germany: 1.234.567,89

- India: 12,34,567.89

Date formatting:

- US: 12/31/2024

- UK: 31/12/2024

- ISO: 2024-12-31

- Japan: 2024年12月31日

Text direction:

- Most languages: left-to-right

- Arabic, Hebrew: right-to-left

- Some Asian: top-to-bottom

12.2 Locale-Aware String Operations

import locale

# Set locale for sorting

locale.setlocale(locale.LC_ALL, 'de_DE.UTF-8')

words = ['Apfel', 'Äpfel', 'Birne', 'Banane']

sorted(words) # Simple sort: ['Apfel', 'Banane', 'Birne', 'Äpfel']

sorted(words, key=locale.strxfrm) # German: ['Apfel', 'Äpfel', 'Banane', 'Birne']

# For more control, use PyICU

from icu import Collator, Locale

collator = Collator.createInstance(Locale('de_DE'))

sorted(words, key=collator.getSortKey)

12.3 Text Segmentation

Word boundaries vary by language:

English: "Hello world" → ["Hello", "world"]

Chinese: "你好世界" → ["你好", "世界"] (needs dictionary)

Thai: "สวัสดีโลก" → ["สวัสดี", "โลก"] (no spaces!)

German: "Donaudampfschifffahrt" → compound word

Use UAX #29 (Unicode Text Segmentation) or ICU:

from icu import BreakIterator, Locale

def get_words(text, locale_str='en_US'):

bi = BreakIterator.createWordInstance(Locale(locale_str))

bi.setText(text)

words = []

start = 0

for end in bi:

word = text[start:end].strip()

if word:

words.append(word)

start = end

return words

get_words("Hello, world!") # ['Hello', 'world']

12.4 Message Formatting

# Simple string formatting loses context

f"You have {count} message{'s' if count != 1 else ''}"

# Better: Use ICU message format

from icu import MessageFormat

pattern = "{count, plural, =0 {No messages} =1 {One message} other {{count} messages}}"

formatter = MessageFormat(pattern, Locale('en_US'))

result = formatter.format({'count': 5}) # "5 messages"

# Even better for translations: Use gettext or similar

import gettext

_ = gettext.gettext

ngettext = gettext.ngettext

ngettext("%(count)d message", "%(count)d messages", count) % {'count': count}

12.5 Right-to-Left UI Considerations

RTL layouts need more than text direction:

Mirror UI elements:

- Back button: left → right

- Progress bars: left-to-right → right-to-left

- Checkboxes: left of label → right of label

Bidirectional icons:

- Arrows should flip

- Play/rewind buttons should flip

- Some icons are neutral (search, settings)

CSS for RTL:

html[dir="rtl"] .arrow-icon {

transform: scaleX(-1);

}

Testing:

- Force RTL mode

- Use pseudo-translation with RTL characters

- Test with real translators

13. Unicode Security Considerations

Text can be weaponized in surprising ways.

13.1 Homograph Attacks

Confusable characters enable spoofing:

Latin 'a' (U+0061) vs Cyrillic 'а' (U+0430)

Latin 'e' (U+0065) vs Cyrillic 'е' (U+0435)

Latin 'o' (U+006F) vs Greek 'ο' (U+03BF)

Digit '0' (U+0030) vs Latin 'O' (U+004F)

Attack: Register payрal.com (Cyrillic 'р')

Victim sees: paypal.com

Defenses:

1. Punycode display for mixed-script domains

2. Confusable detection algorithms

3. Visual similarity warnings

13.2 Unicode Normalization Attacks

# Bypassing filters with non-normalized input

# Attacker input (decomposed)

user_input = "cafe\u0301" # e + combining acute

# Naive filter (won't match!)

if "café" in user_input: # Uses precomposed é

block()

# Fix: Always normalize before comparison

import unicodedata

normalized = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', user_input)

if "café" in normalized:

block()

13.3 Bidi Override Attacks

Bidirectional overrides can hide malicious content:

File: harmless[U+202E]cod.exe

Displays as: harmlessexe.doc

Attack in code comments:

/* check admin [U+202E] } if(isAdmin) { [U+2066] */

Could flip the logic visually while code executes differently.

Defense:

- Strip or escape bidi control characters

- Highlight suspicious Unicode in code review tools

13.4 Text Length Attacks

Length checks can fail with Unicode:

// Max 50 characters?

input.length <= 50 // JavaScript counts UTF-16 code units

Attack: 50 emoji = 100+ code units = lots of bytes

Defense:

- Check byte length for storage limits

- Check grapheme count for user-visible limits

- Validate at multiple levels

13.5 Width Attacks

Zero-width characters are invisible:

"admin" vs "adm\u200Bin"

Both display as "admin", but are different strings!

Attack applications:

- Bypass keyword filters

- Evade duplicate detection

- Hide content in watermarks

Defense:

import re

clean = re.sub(r'[\u200b-\u200f\u2028-\u202f\u2060-\u206f\ufeff]', '', text)

14. Performance Considerations

Unicode operations can be expensive.

14.1 Encoding and Decoding Costs

import timeit

text = "Hello, 世界! 🌍" * 1000

# Encoding benchmarks

timeit.timeit(lambda: text.encode('utf-8'), number=10000)

timeit.timeit(lambda: text.encode('utf-16'), number=10000)

timeit.timeit(lambda: text.encode('utf-32'), number=10000)

# UTF-8 is typically fastest for mixed content

# Results vary by content and platform

14.2 Normalization Costs

import unicodedata

import timeit

text = "café résumé naïve" * 1000

# Normalization is expensive

timeit.timeit(lambda: unicodedata.normalize('NFC', text), number=1000)

# Optimization: Check if already normalized

if not unicodedata.is_normalized('NFC', text):

text = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', text)

14.3 String Operations at Scale

O(n) operations on Unicode strings:

- Finding string length in graphemes

- Case conversion

- Normalization

- Collation key generation

Optimization strategies:

1. Cache normalized/processed text

2. Use byte-level operations when possible

3. Process in streaming fashion for large text

4. Use specialized libraries (ICU, regex)

14.4 Memory Considerations

String memory usage varies by encoding:

"Hello":

- UTF-8: 5 bytes

- UTF-16: 10 bytes

- UTF-32: 20 bytes

"你好":

- UTF-8: 6 bytes

- UTF-16: 4 bytes

- UTF-32: 8 bytes

"Hello 你好":

- UTF-8: 12 bytes (most compact for mixed)

- UTF-16: 14 bytes

- UTF-32: 28 bytes

Python 3 uses flexible string representation:

- ASCII-only: 1 byte per character

- Latin-1 range: 1 byte per character

- BMP: 2 bytes per character

- Full Unicode: 4 bytes per character

15. Testing with Unicode

Ensure your code handles text correctly.

15.1 Test Data Categories

Essential test strings:

1. ASCII only: "Hello World"

2. Latin extended: "Héllo Wörld"

3. Non-Latin scripts: "Привет мир", "שלום עולם"

4. CJK: "你好世界", "こんにちは"

5. Emoji: "Hello 🌍 World 👋"

6. Combining characters: "e\u0301" (e + acute)

7. ZWJ sequences: "👨👩👧👦"

8. RTL text: "مرحبا"

9. Mixed direction: "Hello مرحبا World"

10. Edge cases: Empty string, very long text

15.2 The Torture Test

# A string designed to break things

UNICODE_TORTURE = (

"Hello" # ASCII

"\u0000" # Null byte

"Wörld" # Latin-1

" \u202E\u0635\u0648\u0631\u0629" # RTL override

" 中文" # CJK

" \U0001F600" # Emoji (high plane)

" a\u0308\u0304" # Multiple combining marks

" \u200B" # Zero-width space

" \uFEFF" # BOM

" \U0001F468\u200D\U0001F469\u200D\U0001F467" # ZWJ family

" \n\r\n\r" # Mixed newlines

)

def test_survives_torture(func):

"""Test that a function handles extreme Unicode."""

try:

result = func(UNICODE_TORTURE)

# Verify result is valid string

assert isinstance(result, str)

result.encode('utf-8') # Must be encodable

except Exception as e:

pytest.fail(f"Unicode torture test failed: {e}")

15.3 Property-Based Testing

from hypothesis import given, strategies as st

@given(st.text())

def test_normalize_roundtrip(s):

"""Normalized text should stay normalized."""

import unicodedata

normalized = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', s)

double_normalized = unicodedata.normalize('NFC', normalized)

assert normalized == double_normalized

@given(st.text())

def test_utf8_roundtrip(s):

"""UTF-8 encoding should round-trip."""

encoded = s.encode('utf-8')

decoded = encoded.decode('utf-8')

assert s == decoded

15.4 Visual Inspection Tools

def debug_unicode(text):

"""Print detailed Unicode information."""

import unicodedata

print(f"String: {repr(text)}")

print(f"Length: {len(text)} code points")

print(f"UTF-8 bytes: {len(text.encode('utf-8'))}")

print()

for i, char in enumerate(text):

code = ord(char)

name = unicodedata.name(char, '<unnamed>')

cat = unicodedata.category(char)

print(f" [{i}] U+{code:04X} {cat} {name}")

debug_unicode("café")

# [0] U+0063 Ll LATIN SMALL LETTER C

# [1] U+0061 Ll LATIN SMALL LETTER A

# [2] U+0066 Ll LATIN SMALL LETTER F

# [3] U+00E9 Ll LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH ACUTE

16. The Future of Unicode

Unicode continues to evolve.

16.1 Recent Developments

Unicode 15.0-16.0 additions:

- New emoji (every year)

- Historical scripts (Kawi, Nag Mundari)

- Additional CJK characters

- Symbol sets for technical domains

Trends:

- Emoji remain controversial (standardization process)

- More complex emoji sequences

- Better support for minority languages

- Improved security recommendations

16.2 Emerging Challenges

Still difficult areas:

1. Emoji rendering consistency

- Different platforms show different images

- ZWJ sequences may not be supported everywhere

2. Language identification

- Shared scripts (Latin used by many languages)

- Mixed-language text

3. Accessibility

- Screen readers and Unicode

- Braille encoding

- Sign language notation

4. Digital preservation

- Legacy encoding conversion

- Long-term format stability

16.3 Implementation Improvements

Library and runtime improvements:

Swift: Native grapheme cluster handling

Rust: Strong encoding guarantees

Go: Easy conversion, explicit rune type

Web: Better Intl API support

Future directions:

- Faster normalization algorithms

- Better default behaviors

- Improved tooling for developers

- Standard confusable detection APIs

17. Quick Reference

Essential Unicode information at a glance.

17.1 Common Code Points

Spaces:

U+0020 Space

U+00A0 No-Break Space ( )

U+2003 Em Space

U+3000 Ideographic Space

Control:

U+0000 Null

U+0009 Tab

U+000A Line Feed (LF)

U+000D Carriage Return (CR)

Format:

U+200B Zero Width Space

U+200C Zero Width Non-Joiner

U+200D Zero Width Joiner (ZWJ)

U+FEFF Byte Order Mark

Replacement:

U+FFFD Replacement Character (�)

17.2 UTF-8 Byte Patterns

1-byte: 0xxxxxxx (ASCII)

2-byte: 110xxxxx 10xxxxxx

3-byte: 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

4-byte: 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

Leading byte tells you sequence length:

0x00-0x7F: 1 byte (ASCII)

0xC0-0xDF: 2 bytes

0xE0-0xEF: 3 bytes

0xF0-0xF7: 4 bytes

0x80-0xBF: Continuation byte

17.3 Essential Regex Patterns

import re

# Match any Unicode letter

letters = re.compile(r'\p{L}+', re.UNICODE) # Requires regex module

# Match emoji (basic)

emoji = re.compile(r'[\U0001F600-\U0001F64F]')

# Match zero-width characters

zwc = re.compile(r'[\u200B-\u200D\uFEFF]')

# Match combining marks

combining = re.compile(r'\p{M}', re.UNICODE) # Requires regex module

17.4 Language Comparison Cheat Sheet

Length (code points):

Python 3: len(s)

JavaScript: [...s].length

Java: s.codePointCount(0, s.length())

Rust: s.chars().count()

Go: utf8.RuneCountInString(s)

Length (bytes as UTF-8):

Python 3: len(s.encode('utf-8'))

JavaScript: new TextEncoder().encode(s).length

Java: s.getBytes(StandardCharsets.UTF_8).length

Rust: s.len()

Go: len(s)

Iterate code points:

Python 3: for c in s

JavaScript: for (const c of s)

Java: s.codePoints().forEach(...)

Rust: for c in s.chars()

Go: for _, r := range s

18. Summary

Unicode and character encoding are foundational to working with text in software:

Encoding fundamentals:

- ASCII: 7-bit, 128 characters

- Unicode: Abstract code points (U+0000 to U+10FFFF)

- UTF-8: Variable-width, ASCII-compatible, web standard

- UTF-16: Fixed/variable, used in Windows/Java/JavaScript

- UTF-32: Fixed-width, simple but wasteful

Complexity beyond code points:

- Combining characters build graphemes

- Emoji can be many code points

- Normalization makes equivalent strings equal

- Bidirectional text requires special handling

Best practices:

- Always use UTF-8 for interchange

- Be explicit about encoding at every boundary

- Normalize consistently (NFC recommended)

- Don’t assume string length means characters

- Test with diverse international text

Common pitfalls:

- Mojibake from encoding mismatch

- Double encoding

- Surrogate pair handling in UTF-16

- Security issues with lookalike characters

- Invisible characters in user input

Debugging checklist:

When you encounter text that looks wrong, work through this mental checklist. First, confirm the actual bytes on disk or in transit—hex dump the raw data rather than trusting what a text editor shows. Second, identify what encoding the producer intended versus what the consumer assumed. Third, check whether there’s an additional layer of encoding (like HTML entities on top of UTF-8). Fourth, examine whether the display font actually supports the glyphs in question. Fifth, verify that no intermediate system silently transcoded the data. This systematic approach resolves most encoding mysteries within minutes.

Understanding text encoding deeply will save you countless hours of debugging mysterious “character” bugs. The journey from telegraph codes through ASCII’s pragmatic 7 bits to Unicode’s comprehensive code space reflects humanity’s expanding need to communicate across linguistic boundaries. Today’s systems inherit layers of historical compromise, but UTF-8 provides a clean path forward. The systems are complex, but the core principles are learnable. When in doubt, use UTF-8, normalize to NFC, and test with real multilingual data. Your future self—and your international users—will thank you for taking the time to understand these fundamentals properly.