Virtual Memory and Page Tables: How Modern Systems Manage Memory

A comprehensive exploration of virtual memory, page tables, and address translation. Learn how operating systems provide memory isolation, enable overcommitment, and optimize performance with TLBs and huge pages.

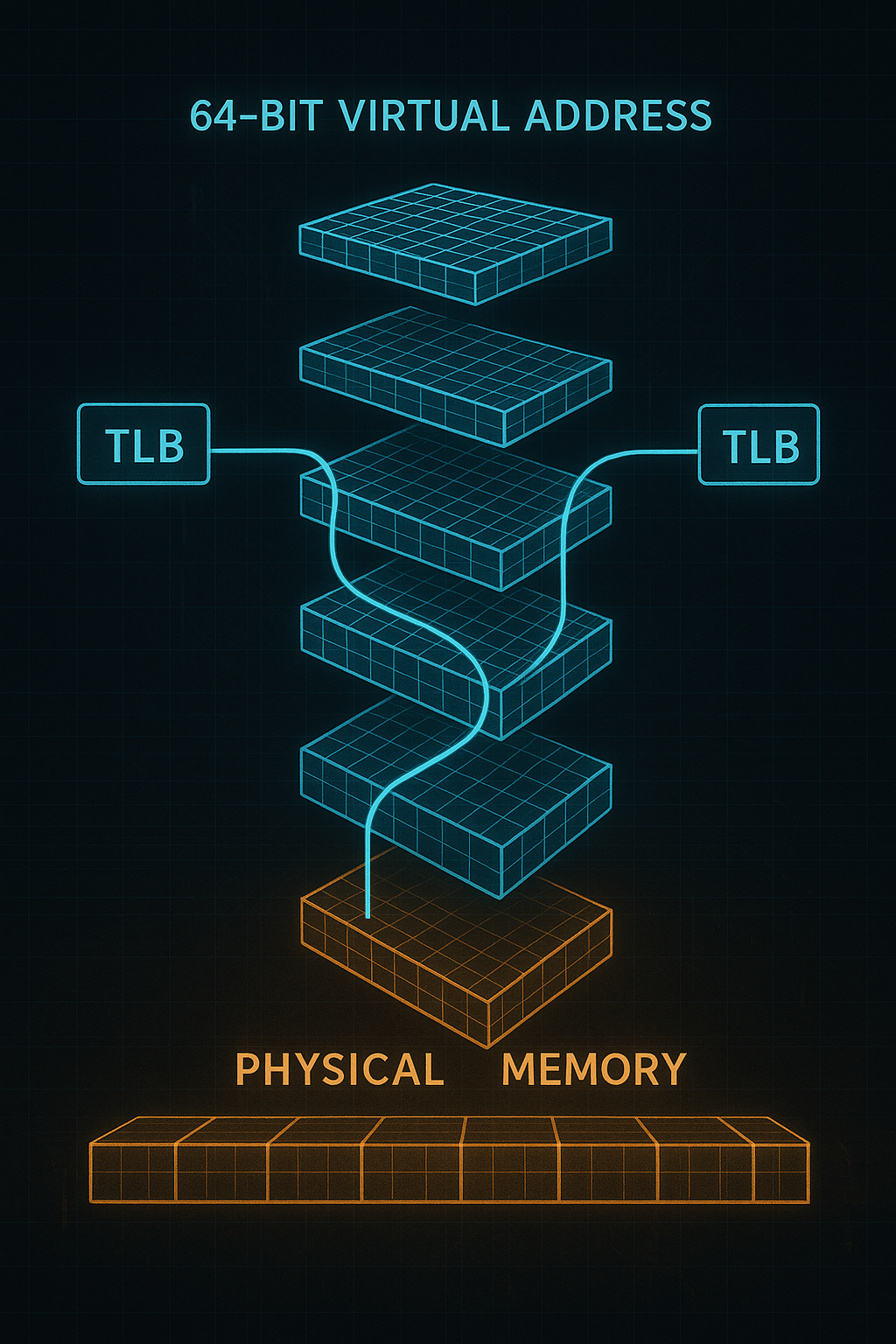

Every process believes it has exclusive access to a vast, contiguous memory space. This elegant illusion—virtual memory—is one of the most important abstractions in computing. Behind it lies a sophisticated system of page tables, TLBs, and hardware-software cooperation that enables memory isolation, efficient sharing, and seemingly infinite memory. Let’s explore how it all works.

1. The Problem: Why Virtual Memory?

Before virtual memory, programs used physical addresses directly. This created serious problems.

1.1 Memory Isolation

Without isolation, any process could read or corrupt another’s memory:

// In a world without virtual memory

int *ptr = (int *)0x12345678; // Physical address

*ptr = 0xDEADBEEF; // Might corrupt the kernel!

Modern systems prevent this entirely. Each process has its own address space:

// With virtual memory

int *ptr = (int *)0x12345678; // Virtual address

*ptr = 0xDEADBEEF; // Only affects THIS process's memory

Two processes can use the same virtual address, but they map to different physical locations.

1.2 Memory Overcommitment

Physical RAM is limited, but virtual address spaces are vast:

Physical RAM: 16 GB

Virtual space: 128 TB (per process on x86-64)

Number of processes: 100+

Total virtual memory: 100 × 128 TB = 12,800 TB

Virtual memory enables this overcommitment through:

- Demand paging: Pages are allocated only when first accessed

- Swapping: Unused pages move to disk

- Sharing: Common pages (libc, kernel) are mapped once

1.3 Memory Fragmentation

Physical memory becomes fragmented over time:

Physical memory after hours of use:

[Used][Free][Used][Free][Used][Used][Free][Used][Free]

Contiguous virtual allocation:

[ Contiguous 16KB virtual buffer ]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

[4KB][ ][4KB][ ][4KB][4KB][ ][4KB]

scattered across physical memory

Virtual memory provides contiguous virtual addresses backed by scattered physical pages.

1.4 Position-Independent Code

Without virtual memory, programs need relocation at load time:

// Without virtual memory: absolute addresses compiled in

call 0x401000 // What if another program is using that address?

// With virtual memory: every process starts at the same virtual address

call 0x401000 // Each process has its own 0x401000

2. Pages and Frames

Virtual memory divides memory into fixed-size units.

2.1 Terminology

- Page: A fixed-size block of virtual memory (typically 4KB)

- Frame: A fixed-size block of physical memory (same size as page)

- Page table: Data structure mapping virtual pages to physical frames

Virtual Address Space Physical Memory

┌───────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────┐

│ Page 0 (0x0000) │ ──────── │ Frame 7 │

├───────────────────┤ ├───────────────────┤

│ Page 1 (0x1000) │ ──────── │ Frame 2 │

├───────────────────┤ ├───────────────────┤

│ Page 2 (0x2000) │ ──╳ │ Frame 3 │

├───────────────────┤ (not ├───────────────────┤

│ Page 3 (0x3000) │ ──────── │ Frame 5 │

└───────────────────┘ mapped) └───────────────────┘

2.2 Address Translation

A virtual address is split into page number and offset:

32-bit virtual address with 4KB pages:

┌─────────────────────────┬──────────────┐

│ Page Number (20 bits)│ Offset (12) │

└─────────────────────────┴──────────────┘

↓

Page Table Lookup

↓

┌─────────────────────────┬──────────────┐

│ Frame Number (20 bits)│ Offset (12) │

└─────────────────────────┴──────────────┘

Physical Address

The offset stays the same—only the page/frame number changes:

def translate_address(virtual_addr, page_table, page_size=4096):

page_number = virtual_addr // page_size

offset = virtual_addr % page_size

if page_number not in page_table:

raise PageFault(page_number)

frame_number = page_table[page_number]

physical_addr = frame_number * page_size + offset

return physical_addr

2.3 Page Table Entries

Each page table entry (PTE) contains more than just the frame number:

x86-64 Page Table Entry (64 bits):

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 63│62:52│51:M │M-1:12 │11:9│8 │7 │6│5│4 │3 │2│1│0│

│NX │ │RSVD │Frame Num │AVL │G │PAT│D│A│PCD│PWT│U│W│P│

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

P = Present (is this page in physical memory?)

W = Writable (can we write to this page?)

U = User (can user-mode code access this?)

A = Accessed (has this page been read?)

D = Dirty (has this page been written?)

G = Global (don't flush from TLB on context switch)

NX = No Execute (prevent code execution from this page)

These bits enable:

- Copy-on-write: Mark pages read-only, copy on write fault

- Demand paging: Mark pages not-present, allocate on fault

- Memory protection: Prevent user access to kernel pages

- DEP/NX: Prevent execution of data pages

3. Multi-Level Page Tables

A flat page table for a 64-bit address space would be enormous.

3.1 The Size Problem

With 4KB pages and 48-bit virtual addresses (256TB):

Number of pages = 2^48 / 2^12 = 2^36 = 64 billion pages

PTE size = 8 bytes

Page table size = 64 billion × 8 = 512 GB per process!

Even for a process using only 1MB of memory, we’d need a 512GB page table.

3.2 Hierarchical Page Tables

The solution: multi-level page tables that are sparse:

x86-64 Four-Level Page Table:

Virtual Address (48 bits used):

┌─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬────────────┐

│PML4 (9) │PDPT (9) │ PD (9) │ PT (9) │Offset (12) │

└────┬────┴────┬────┴────┬────┴────┬────┴────────────┘

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ ┌────────┐

│ PML4 │→│ PDPT │→│ PD │→│ PT │→ Frame

│(512 ent)│ │(512 ent)│ │(512 ent)│ │(512 ent)│

└────────┘ └────────┘ └────────┘ └────────┘

Each level has 512 entries (9 bits), and tables are only allocated as needed:

def translate_4level(virtual_addr, cr3):

"""x86-64 four-level page table walk."""

# Extract indices from virtual address

pml4_idx = (virtual_addr >> 39) & 0x1FF

pdpt_idx = (virtual_addr >> 30) & 0x1FF

pd_idx = (virtual_addr >> 21) & 0x1FF

pt_idx = (virtual_addr >> 12) & 0x1FF

offset = virtual_addr & 0xFFF

# Walk the page table hierarchy

pml4 = read_physical(cr3)

pml4e = pml4[pml4_idx]

if not pml4e.present:

raise PageFault(virtual_addr)

pdpt = read_physical(pml4e.frame_addr)

pdpte = pdpt[pdpt_idx]

if not pdpte.present:

raise PageFault(virtual_addr)

pd = read_physical(pdpte.frame_addr)

pde = pd[pd_idx]

if not pde.present:

raise PageFault(virtual_addr)

pt = read_physical(pde.frame_addr)

pte = pt[pt_idx]

if not pte.present:

raise PageFault(virtual_addr)

return pte.frame_addr + offset

3.3 Memory Savings

For a process using only a few megabytes:

Without hierarchy: 512 GB (fixed)

With hierarchy:

- 1 PML4 table: 4 KB

- 1 PDPT table: 4 KB

- 1 PD table: 4 KB

- 1 PT table: 4 KB

Total: 16 KB (for up to 2 MB of mappings)

Sparse address spaces only allocate the page table entries they need.

3.4 Five-Level Page Tables

Modern CPUs support 5-level paging for 57-bit virtual addresses (128 PB):

LA57 (5-level paging):

┌─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬─────────┬────────────┐

│PML5 (9) │PML4 (9) │PDPT (9) │ PD (9) │ PT (9) │Offset (12) │

└─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴─────────┴────────────┘

This is primarily useful for memory-mapped file systems and persistent memory.

4. The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

Walking the page table for every memory access would be devastatingly slow.

4.1 The Problem

Each memory access requires multiple page table lookups:

Without TLB, reading one byte:

1. Read PML4 entry (memory access)

2. Read PDPT entry (memory access)

3. Read PD entry (memory access)

4. Read PT entry (memory access)

5. Read actual data (memory access)

Total: 5 memory accesses for 1 logical access!

4.2 TLB as a Cache

The TLB caches recent virtual-to-physical translations:

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer):

┌─────────────────┬────────────────┬───────────┐

│ Virtual Page │ Physical Frame │ Flags │

├─────────────────┼────────────────┼───────────┤

│ 0x7fff_8000 │ 0x1234_5000 │ RWX, User │

│ 0x0040_1000 │ 0x0042_3000 │ R-X, User │

│ 0xffff_8000 │ 0x0000_1000 │ RW-, Kern │

│ ... │ ... │ ... │

└─────────────────┴────────────────┴───────────┘

With a TLB hit, translation takes 1 cycle instead of 4 memory accesses.

4.3 TLB Organization

Modern CPUs have multiple TLB levels:

Intel Core i7 TLB Organization:

L1 ITLB (instruction): 128 entries, 4-way set associative

L1 DTLB (data): 64 entries, 4-way set associative

L2 STLB (unified): 1536 entries, 12-way set associative

TLB miss rates are typically < 1% for most workloads.

4.4 TLB Management

The OS must manage TLB consistency:

// When page tables change, flush affected TLB entries

// Flush entire TLB (expensive)

void flush_tlb_all(void) {

unsigned long cr3 = read_cr3();

write_cr3(cr3); // Writing CR3 flushes entire TLB

}

// Flush single page (x86 INVLPG instruction)

void flush_tlb_page(unsigned long addr) {

asm volatile("invlpg (%0)" : : "r" (addr) : "memory");

}

// Flush range of pages

void flush_tlb_range(unsigned long start, unsigned long end) {

for (unsigned long addr = start; addr < end; addr += PAGE_SIZE) {

flush_tlb_page(addr);

}

}

TLB shootdowns are needed for multi-core systems:

// TLB shootdown: flush TLB on all CPUs

void flush_tlb_all_cpus(unsigned long addr) {

// Send IPI (Inter-Processor Interrupt) to all CPUs

for_each_online_cpu(cpu) {

if (cpu != current_cpu) {

send_ipi(cpu, TLB_FLUSH_IPI);

}

}

flush_tlb_page(addr);

wait_for_ack_from_all_cpus();

}

TLB shootdowns are expensive and can become a bottleneck for applications with heavy page table modifications.

5. Page Faults

When translation fails, the CPU triggers a page fault.

5.1 Types of Page Faults

void handle_page_fault(unsigned long address, unsigned long error_code) {

struct vm_area_struct *vma = find_vma(current->mm, address);

if (!vma || address < vma->vm_start) {

// Segmentation fault: address not mapped

send_signal(SIGSEGV, current);

return;

}

if (error_code & PF_WRITE && !(vma->vm_flags & VM_WRITE)) {

if (vma->vm_flags & VM_MAYWRITE) {

// Copy-on-write fault

handle_cow_fault(vma, address);

} else {

// Permission violation

send_signal(SIGSEGV, current);

}

return;

}

if (!(error_code & PF_PRESENT)) {

// Page not in memory

if (vma->vm_file) {

// Memory-mapped file: read from disk

handle_file_fault(vma, address);

} else {

// Anonymous page: allocate zeroed page

handle_anon_fault(vma, address);

}

}

}

5.2 Demand Paging

Pages are allocated only when first accessed:

void *ptr = mmap(NULL, 1024*1024*1024, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

// No physical memory allocated yet!

ptr[0] = 'A'; // Page fault → allocate page 0

ptr[4096] = 'B'; // Page fault → allocate page 1

// Only 8KB of physical memory used for a 1GB mapping

This enables memory overcommitment:

// Linux can promise more memory than physically exists

// vm.overcommit_memory controls this behavior

// Check how much memory is "committed" vs available

// /proc/meminfo: Committed_AS vs CommitLimit

5.3 Copy-on-Write (COW)

When a process forks, pages are shared until written:

pid_t pid = fork();

// Parent and child share all pages (marked read-only)

if (pid == 0) {

// Child writes to a shared page

global_variable = 42;

// Page fault → kernel copies the page

// Child gets its own copy, parent's unchanged

}

This makes fork() nearly instantaneous, even for large processes.

5.4 Lazy Allocation

Stack and heap grow lazily:

void recursive_function(int depth) {

char buffer[4096]; // Might trigger page fault for stack growth

if (depth > 0) {

recursive_function(depth - 1);

}

}

// Stack limit is typically 8MB, but physical pages

// are allocated only as the stack grows

6. Huge Pages

Standard 4KB pages create overhead for large memory workloads.

6.1 The Problem with Small Pages

For a 128GB database buffer pool:

Number of pages: 128 GB / 4 KB = 32 million pages

TLB entries: ~1536 (L2 STLB)

TLB coverage: 1536 × 4 KB = 6 MB

Only 0.005% of the buffer pool fits in TLB!

Result: Constant TLB misses, performance degradation

6.2 Huge Page Sizes

x86-64 supports larger pages:

Page Size Coverage per TLB entry Use Case

─────────────────────────────────────────────────

4 KB 4 KB General purpose

2 MB 2 MB (512× more) Large allocations

1 GB 1 GB (262144× more) Huge allocations

With 2MB huge pages:

Number of pages: 128 GB / 2 MB = 64,000 pages

TLB coverage: 1536 × 2 MB = 3 GB

Now 2.3% of buffer pool fits in TLB (460× improvement!)

6.3 Using Huge Pages

Linux provides several mechanisms:

// Method 1: mmap with MAP_HUGETLB

void *ptr = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS|MAP_HUGETLB, -1, 0);

// Method 2: Transparent Huge Pages (THP)

// Kernel automatically uses huge pages when possible

// Enable: echo always > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

// Method 3: hugetlbfs

// mount -t hugetlbfs none /mnt/huge

int fd = open("/mnt/huge/myfile", O_CREAT|O_RDWR, 0755);

void *ptr = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

6.4 Huge Page Challenges

Huge pages aren’t free:

Challenge 1: Fragmentation

- Need contiguous 2MB regions

- System may not have them after running a while

- Solution: Reserve huge pages at boot, or use compaction

Challenge 2: Memory waste

- Internal fragmentation: 1 byte allocation wastes 2MB - 1 byte

- Only beneficial for large allocations

Challenge 3: THP latency spikes

- Kernel compaction can cause long pauses

- khugepaged background thread uses CPU

Challenge 4: Memory accounting

- Hard to track actual usage with copy-on-write

- Can cause OOM in unexpected ways

Database best practices:

# Disable THP for databases (causes latency spikes)

echo never > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

echo never > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/defrag

# Use explicit huge pages instead

echo 8192 > /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages # Reserve 16GB in 2MB pages

7. Memory-Mapped Files

Virtual memory enables efficient file I/O through memory mapping.

7.1 How It Works

int fd = open("database.db", O_RDWR);

void *map = mmap(NULL, file_size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

// Reading from the file

int value = ((int *)map)[1000];

// If page not in memory: page fault → kernel reads from disk

// Writing to the file

((int *)map)[1000] = 42;

// Page marked dirty → kernel writes back later (or on msync/munmap)

7.2 Advantages

Memory-mapped files offer several benefits:

// 1. Zero-copy: data goes directly from disk to application memory

// No intermediate kernel buffers

// 2. Automatic caching: kernel page cache handles everything

// Recently accessed pages stay in memory

// 3. Lazy loading: only accessed pages are read from disk

// 4. Shared mappings: multiple processes can share the same pages

int fd = open("shared.db", O_RDWR);

void *map = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

// Changes visible to all processes mapping the same file

7.3 Gotchas

Memory-mapped files have pitfalls:

// Problem 1: I/O errors become signals

void handle_sigbus(int sig) {

// Disk error during page-in causes SIGBUS, not read() error

// Hard to handle gracefully

}

signal(SIGBUS, handle_sigbus);

// Problem 2: No fine-grained control over I/O timing

// Can't prioritize which pages to read first

// Problem 3: Page-sized I/O granularity

// Reading 1 byte still loads entire 4KB page

// Problem 4: Difficult to manage memory pressure

// Can't easily tell the kernel which pages to evict

7.4 madvise Hints

Tell the kernel about access patterns:

// Sequential access: prefetch ahead

madvise(map, size, MADV_SEQUENTIAL);

// Random access: don't prefetch

madvise(map, size, MADV_RANDOM);

// Will need this soon: prefetch pages

madvise(map + offset, length, MADV_WILLNEED);

// Won't need anymore: allow kernel to free pages

madvise(map + offset, length, MADV_DONTNEED);

// Using huge pages would help

madvise(map, size, MADV_HUGEPAGE);

8. Kernel vs. User Address Space

The virtual address space is split between kernel and user.

8.1 Address Space Layout

x86-64 Linux with 4-level paging (48-bit addresses):

User space: 0x0000_0000_0000_0000 - 0x0000_7fff_ffff_ffff (128 TB)

↑

Lower half of address space

[Canonical hole: addresses with bits 48-63 neither all 0s nor all 1s]

Kernel space: 0xffff_8000_0000_0000 - 0xffff_ffff_ffff_ffff (128 TB)

↑

Upper half of address space (all 1s in bits 48-63)

8.2 Why Share the Address Space?

Kernel mappings in every process’s address space:

// System call without shared kernel mapping:

// 1. Save all user registers

// 2. Load kernel page table (CR3 write = TLB flush!)

// 3. Execute system call

// 4. Load user page table (another TLB flush!)

// 5. Restore registers

// With shared mapping:

// 1. Switch to ring 0

// 2. Execute system call (kernel pages already mapped!)

// 3. Return to ring 3

// No page table switch, no TLB flush!

8.3 Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI)

Meltdown vulnerability forced a change:

Before Meltdown/KPTI:

User process sees: [User pages] [Kernel pages (inaccessible but mapped)]

After KPTI:

User mode: [User pages] [Minimal kernel trampoline]

Kernel mode: [User pages] [Full kernel mapping]

Page table switch on every syscall/interrupt - performance cost!

KPTI overhead:

Syscall-heavy workloads: 5-30% slowdown

Memory-mapped I/O: 2-5% slowdown

Compute-heavy: < 1% slowdown

9. NUMA and Virtual Memory

Non-Uniform Memory Access adds complexity to memory management.

9.1 NUMA Architecture

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ NUMA System │

│ ┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Node 0 │ │ Node 1 │ │

│ │ ┌───────────────┐ │ │ ┌───────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ CPU 0-7 │ │ │ │ CPU 8-15 │ │ │

│ │ └───────┬───────┘ │ │ └───────┬───────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ┌───────▼───────┐ │ │ ┌───────▼───────┐ │ │

│ │ │ Local Memory │◄─┼─────┼─►│ Local Memory │ │ │

│ │ │ (fast) │ │ │ │ (fast) │ │ │

│ │ └───────────────┘ │ │ └───────────────┘ │ │

│ └─────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▲ Interconnect (slower than local) ▲ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Memory access latency varies by location:

Local memory access: ~80 ns

Remote memory access: ~140 ns (1.75× slower)

9.2 NUMA-Aware Memory Allocation

#include <numa.h>

// Allocate on specific node

void *ptr = numa_alloc_onnode(size, node);

// Allocate interleaved across all nodes

void *ptr = numa_alloc_interleaved(size);

// Bind memory to nodes

numa_tonode_memory(ptr, size, node);

// Set NUMA policy for allocations

set_mempolicy(MPOL_BIND, &nodemask, maxnode);

9.3 First-Touch Policy

Linux defaults to first-touch allocation:

void *ptr = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

// No physical memory allocated yet

// Thread on node 0 touches the memory first

ptr[0] = 'A';

// Page allocated on node 0

// Thread on node 1 accesses the same page

char c = ptr[0];

// Remote access! 1.75× slower

This can cause performance problems:

// Anti-pattern: initialize memory on one thread, use on another

void init_thread() {

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

buffer[i] = 0; // All pages allocated on init thread's node

}

}

void worker_threads() {

// If workers are on different nodes, all accesses are remote!

}

// Better: parallel first-touch initialization

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

buffer[i] = 0; // Each thread touches pages it will use

}

9.4 NUMA Balancing

Linux can automatically migrate pages:

# Enable automatic NUMA balancing

echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/numa_balancing

# The kernel tracks page access patterns and migrates pages

# to be closer to the threads accessing them

However, migration has overhead:

Page migration cost: Copy 4KB page + TLB flush + update page tables

Worth it only if: Future access savings > migration cost

Kernel uses heuristics: access frequency, migration history

10. Virtual Memory Security

Virtual memory is the foundation of process isolation and security.

10.1 Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

Randomize memory layout to hinder exploits:

# Check ASLR setting

cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

# 0 = disabled, 1 = partial, 2 = full

# Run a program twice, observe different addresses

$ cat /proc/self/maps | head -3

55a3b2c00000-55a3b2c01000 r--p ...

$ cat /proc/self/maps | head -3

559c1a400000-559c1a401000 r--p ... # Different!

ASLR randomizes:

- Stack location

- Heap location

- Library load addresses

- Executable base (PIE)

- mmap regions

10.2 Stack Canaries and Guard Pages

Protect against stack buffer overflows:

void vulnerable_function(char *input) {

char buffer[64];

unsigned long canary = __stack_chk_guard; // Random value

strcpy(buffer, input); // Potential overflow

if (canary != __stack_chk_guard) {

__stack_chk_fail(); // Overflow detected!

}

}

Guard pages prevent stack overflow into other memory:

Stack Layout:

┌──────────────────┐

│ Stack growth ↓ │

├──────────────────┤

│ Guard page │ ← Not mapped, access triggers SIGSEGV

├──────────────────┤

│ Next region │

└──────────────────┘

10.3 W^X (Write XOR Execute)

Pages should never be both writable and executable:

// Allocate non-executable heap (default)

void *heap = malloc(1024); // W, no X

// Allocate non-writable code

void *code = mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0); // R+X, no W

// JIT compilation: write then execute

void *jit = mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0); // W, no X

// ... generate code ...

mprotect(jit, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC); // Now R+X, no W

10.4 Memory Tagging (MTE)

ARM Memory Tagging Extension catches memory safety bugs:

// Each pointer has a 4-bit tag (in unused high bits)

// Each 16-byte granule of memory has a 4-bit tag

// Access checks: pointer tag must match memory tag

char *ptr = tagged_malloc(16); // ptr has tag 0x5, memory has tag 0x5

ptr[0] = 'A'; // Tags match, OK

free(ptr); // Memory tag changed to 0x7

ptr[0] = 'B'; // Tag mismatch! Hardware exception

// Use-after-free detected!

11. Performance Debugging

Understanding virtual memory behavior is crucial for performance.

11.1 Measuring Page Faults

# Count page faults for a process

$ /usr/bin/time -v ./myprogram

Minor (reclaiming a frame) page faults: 12345

Major (requiring I/O) page faults: 100

# Live monitoring

$ perf stat -e page-faults,minor-faults,major-faults ./myprogram

// Programmatic monitoring

#include <sys/resource.h>

struct rusage usage;

getrusage(RUSAGE_SELF, &usage);

printf("Minor faults: %ld\n", usage.ru_minflt);

printf("Major faults: %ld\n", usage.ru_majflt);

11.2 TLB Profiling

# Measure TLB misses

$ perf stat -e dTLB-load-misses,dTLB-store-misses,iTLB-load-misses ./myprogram

# TLB miss ratio

$ perf stat -e dTLB-loads,dTLB-load-misses ./myprogram

# 1,000,000 dTLB-loads

# 10,000 dTLB-load-misses # 1% miss rate

High TLB miss rates suggest:

- Working set too large for TLB

- Consider huge pages

- Improve memory locality

11.3 Memory Access Patterns

# Visualize memory access patterns

$ perf record -e mem_load_retired.l3_miss ./myprogram

$ perf report

# Memory bandwidth and latency

$ perf stat -e cache-references,cache-misses ./myprogram

11.4 Common Performance Issues

Issue: High major page fault rate

Cause: Memory pressure, frequent swapping

Fix: Add RAM, reduce memory usage, tune swappiness

Issue: High TLB miss rate

Cause: Large working set, scattered access patterns

Fix: Use huge pages, improve locality

Issue: NUMA imbalance

Cause: Memory on wrong node, poor first-touch

Fix: numactl binding, parallel initialization

Issue: High syscall overhead (with KPTI)

Cause: Frequent user/kernel transitions

Fix: Batch syscalls, use io_uring

12. Virtual Memory Across Operating Systems

Different operating systems implement virtual memory with their own approaches and optimizations.

12.1 Linux

Linux’s virtual memory system is highly configurable:

# Key tunables in /proc/sys/vm/

# Swappiness: tendency to swap vs. drop cache (0-100)

cat /proc/sys/vm/swappiness # Default 60

# Overcommit behavior

cat /proc/sys/vm/overcommit_memory

# 0 = heuristic, 1 = always overcommit, 2 = never overcommit

# Dirty page writeback thresholds

cat /proc/sys/vm/dirty_ratio # % of RAM for dirty pages

cat /proc/sys/vm/dirty_background_ratio # Start background writeback

# Huge page settings

cat /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages

cat /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

Linux memory zones:

Zone Purpose

─────────────────────────────────

ZONE_DMA Legacy 16MB for ISA DMA

ZONE_DMA32 Memory addressable by 32-bit DMA

ZONE_NORMAL Regular memory

ZONE_MOVABLE For memory hotplug/migration

12.2 Windows

Windows uses a different terminology and approach:

Windows Memory Concepts:

─────────────────────────

Working Set: Pages currently in physical memory

Commit Charge: Total virtual memory committed

Paged Pool: Kernel memory that can be paged out

Nonpaged Pool: Kernel memory that must stay resident

Windows memory management differs from Linux in several ways:

// Windows API for memory management

LPVOID VirtualAlloc(

LPVOID lpAddress,

SIZE_T dwSize,

DWORD flAllocationType, // MEM_RESERVE, MEM_COMMIT

DWORD flProtect

);

// Reserve address space without committing physical memory

void *reserved = VirtualAlloc(NULL, 1GB, MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_NOACCESS);

// Later, commit portions as needed

void *committed = VirtualAlloc(reserved, 4096, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

Windows has distinct reserve and commit operations, unlike Linux’s implicit overcommit.

12.3 FreeBSD

FreeBSD’s virtual memory system has unique characteristics:

FreeBSD VM Features:

─────────────────────────────────────────

Superpages: Automatic huge page promotion

VM objects: Copy-on-write at object level

Swap clustering: Group pages for efficient swap I/O

NUMA domains: First-class NUMA support

12.4 macOS

macOS builds on Mach microkernel VM concepts:

// Mach VM API

vm_allocate(mach_task_self(), &address, size, VM_FLAGS_ANYWHERE);

vm_deallocate(mach_task_self(), address, size);

// Memory pressure notifications

dispatch_source_t source = dispatch_source_create(

DISPATCH_SOURCE_TYPE_MEMORYPRESSURE,

0,

DISPATCH_MEMORYPRESSURE_WARN | DISPATCH_MEMORYPRESSURE_CRITICAL,

queue

);

macOS aggressive compression:

macOS Memory Compression:

─────────────────────────

Instead of swapping to disk immediately, macOS compresses inactive pages

in memory. Decompression is much faster than disk I/O.

Typical compression ratio: 2-3x

Result: More effective RAM, less swap I/O

13. Advanced Topics

13.1 Persistent Memory

Intel Optane and similar technologies blur the line between memory and storage:

#include <libpmem.h>

// Map persistent memory

void *pmem = pmem_map_file("/pmem/data", size,

PMEM_FILE_CREATE, 0666, &mapped_size, &is_pmem);

// Writes are durable after flush

memcpy(pmem + offset, data, len);

pmem_persist(pmem + offset, len); // Data survives power loss!

This changes virtual memory assumptions:

Traditional:

Virtual Address → Physical RAM → (volatile, lost on power loss)

With Persistent Memory:

Virtual Address → Physical PMEM → (durable, survives reboot)

13.2 Memory Ballooning

Hypervisors use ballooning to reclaim memory from VMs:

Balloon Driver Operation:

1. Hypervisor wants to reclaim 1GB from VM

2. Sends signal to balloon driver in guest

3. Balloon driver allocates 1GB of guest memory

4. Guest OS pages out or compresses that memory

5. Balloon driver tells hypervisor which physical pages to reclaim

6. Hypervisor unmaps those pages, can give to other VMs

// Linux virtio_balloon driver

static void balloon_inflate(struct virtio_balloon *vb) {

struct page *page = alloc_page(GFP_KERNEL);

list_add(&page->lru, &vb->pages);

tell_host_about_page(page); // Hypervisor can reclaim this

}

13.3 Memory Hotplug

Adding or removing memory while the system runs:

# Check available memory blocks

ls /sys/devices/system/memory/

# Online a new memory block

echo online > /sys/devices/system/memory/memory32/state

# Offline memory (requires pages to be migrated first)

echo offline > /sys/devices/system/memory/memory32/state

Challenges:

Offlining Memory:

1. Cannot offline pages with kernel data structures

2. Must migrate movable pages to other memory

3. Huge pages complicate migration

4. Some memory is inherently unmovable (kernel text)

13.4 Kernel Same-page Merging (KSM)

Deduplicate identical pages across processes:

// Mark memory region as mergeable

madvise(addr, size, MADV_MERGEABLE);

KSM operation:

1. ksmd kernel thread scans mergeable pages

2. Computes hash of each page

3. Compares pages with same hash

4. Identical pages merged (copy-on-write)

5. Significant memory savings for VMs with same OS

Trade-offs:

Benefits:

- Memory savings (especially for VMs running same OS)

- Can overcommit more aggressively

Costs:

- CPU overhead for scanning and hashing

- Memory access latency (copy-on-write faults)

- Security concern: timing attacks can detect merging

14. Historical Context and Evolution

14.1 Pre-Virtual Memory Era

Early systems used physical addresses directly:

1950s-1960s:

- Programs loaded at fixed addresses

- Only one program in memory at a time

- Manual memory management (overlays)

14.2 Segmentation

Before paging, segmentation provided some isolation:

Intel 8086 Segmentation:

Physical Address = (Segment × 16) + Offset

Segments provided:

- Code segment (CS)

- Data segment (DS)

- Stack segment (SS)

- Extra segment (ES)

Segments were variable-sized, leading to fragmentation.

14.3 Paging Revolution

Atlas Computer (1962) introduced paging:

Key innovations:

- Fixed-size pages (512 words)

- Demand paging

- Page replacement algorithms

- Virtual addresses transparent to programs

14.4 Modern Evolution

1990s: PAE (36-bit physical addresses on 32-bit x86)

2000s: x86-64 (48-bit virtual, later 57-bit)

2010s: Virtualization extensions (EPT/NPT)

2018: Hardware mitigations (KPTI, Retpoline)

2020s: Memory tagging, CXL memory expansion

15. Practical Implementation Example

Let’s implement a simple page table simulator to solidify understanding:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Optional, Dict

from enum import IntFlag

class PageFlags(IntFlag):

PRESENT = 1 << 0

WRITABLE = 1 << 1

USER = 1 << 2

ACCESSED = 1 << 3

DIRTY = 1 << 4

NO_EXECUTE = 1 << 63

@dataclass

class PageTableEntry:

frame_number: int

flags: PageFlags

def is_present(self) -> bool:

return bool(self.flags & PageFlags.PRESENT)

def is_writable(self) -> bool:

return bool(self.flags & PageFlags.WRITABLE)

class PageTable:

"""Simple single-level page table for demonstration."""

def __init__(self, page_size: int = 4096):

self.page_size = page_size

self.entries: Dict[int, PageTableEntry] = {}

self.tlb: Dict[int, int] = {} # Virtual page -> Physical frame cache

self.tlb_hits = 0

self.tlb_misses = 0

def map_page(self, virtual_page: int, physical_frame: int,

flags: PageFlags = PageFlags.PRESENT | PageFlags.WRITABLE) -> None:

"""Map a virtual page to a physical frame."""

self.entries[virtual_page] = PageTableEntry(physical_frame, flags)

# Invalidate TLB entry if exists

if virtual_page in self.tlb:

del self.tlb[virtual_page]

def unmap_page(self, virtual_page: int) -> None:

"""Unmap a virtual page."""

if virtual_page in self.entries:

del self.entries[virtual_page]

if virtual_page in self.tlb:

del self.tlb[virtual_page]

def translate(self, virtual_addr: int, write: bool = False) -> int:

"""Translate a virtual address to physical address."""

virtual_page = virtual_addr // self.page_size

offset = virtual_addr % self.page_size

# Check TLB first

if virtual_page in self.tlb:

self.tlb_hits += 1

physical_frame = self.tlb[virtual_page]

else:

self.tlb_misses += 1

# Walk page table

if virtual_page not in self.entries:

raise PageFault(virtual_addr, "Page not mapped")

entry = self.entries[virtual_page]

if not entry.is_present():

raise PageFault(virtual_addr, "Page not present")

if write and not entry.is_writable():

raise PageFault(virtual_addr, "Write to read-only page")

# Update accessed/dirty bits

entry.flags |= PageFlags.ACCESSED

if write:

entry.flags |= PageFlags.DIRTY

physical_frame = entry.frame_number

# Cache in TLB

self.tlb[virtual_page] = physical_frame

return physical_frame * self.page_size + offset

def flush_tlb(self) -> None:

"""Flush entire TLB."""

self.tlb.clear()

def get_stats(self) -> dict:

"""Return TLB statistics."""

total = self.tlb_hits + self.tlb_misses

hit_rate = self.tlb_hits / total if total > 0 else 0

return {

"tlb_hits": self.tlb_hits,

"tlb_misses": self.tlb_misses,

"hit_rate": hit_rate

}

class PageFault(Exception):

def __init__(self, address: int, reason: str):

self.address = address

self.reason = reason

super().__init__(f"Page fault at 0x{address:x}: {reason}")

class VirtualMemorySimulator:

"""Simulates a simple virtual memory system."""

def __init__(self, physical_memory_size: int = 1024 * 1024):

self.page_table = PageTable()

self.physical_memory = bytearray(physical_memory_size)

self.next_free_frame = 0

self.page_size = 4096

def allocate_frame(self) -> int:

"""Allocate a physical frame."""

frame = self.next_free_frame

self.next_free_frame += 1

return frame

def mmap(self, virtual_addr: int, size: int) -> None:

"""Map a region of virtual memory."""

start_page = virtual_addr // self.page_size

num_pages = (size + self.page_size - 1) // self.page_size

for i in range(num_pages):

frame = self.allocate_frame()

self.page_table.map_page(start_page + i, frame)

def read(self, virtual_addr: int) -> int:

"""Read a byte from virtual memory."""

try:

physical_addr = self.page_table.translate(virtual_addr)

return self.physical_memory[physical_addr]

except PageFault as e:

# Handle page fault - in real OS, would allocate/swap in

print(f"Page fault: {e}")

raise

def write(self, virtual_addr: int, value: int) -> None:

"""Write a byte to virtual memory."""

try:

physical_addr = self.page_table.translate(virtual_addr, write=True)

self.physical_memory[physical_addr] = value

except PageFault as e:

print(f"Page fault: {e}")

raise

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

vm = VirtualMemorySimulator()

# Map 16KB starting at virtual address 0x1000

vm.mmap(0x1000, 16384)

# Write and read some data

vm.write(0x1000, 42)

vm.write(0x1001, 43)

print(f"Read 0x1000: {vm.read(0x1000)}") # 42

print(f"Read 0x1001: {vm.read(0x1001)}") # 43

# Check TLB stats

print(vm.page_table.get_stats())

# Access unmapped memory

try:

vm.read(0x9000) # Not mapped

except PageFault as e:

print(f"Caught: {e}")

This simplified implementation demonstrates:

- Page table structure and lookup

- TLB caching for fast translation

- Page fault handling

- Address decomposition into page number and offset

Production implementations add multi-level tables, hardware acceleration, and integration with the physical memory allocator.

16. Summary

Virtual memory is one of the most elegant abstractions in computing:

Core concepts:

- Pages and frames divide memory into fixed-size chunks

- Page tables map virtual addresses to physical addresses

- Multi-level page tables handle sparse address spaces efficiently

- TLBs cache translations for fast access

Key mechanisms:

- Demand paging allocates memory lazily

- Copy-on-write enables efficient process forking

- Memory-mapped files provide zero-copy I/O

- Huge pages reduce TLB pressure for large allocations

Performance considerations:

- TLB misses can dominate memory-intensive workloads

- NUMA awareness is critical for multi-socket systems

- Page faults are expensive—minimize major faults

- Memory layout affects cache and TLB efficiency

Security foundations:

- Address space isolation protects processes from each other

- ASLR randomizes memory layout to hinder exploits

- W^X prevents code injection attacks

- Memory tagging catches memory safety bugs in hardware

Understanding virtual memory transforms how you think about system performance. Whether you’re debugging mysterious slowdowns, optimizing database buffer pools, or securing applications against memory attacks, this knowledge is foundational to effective systems programming.