Virtual Memory and Page Tables: How Operating Systems Manage Memory

A comprehensive exploration of virtual memory systems, page tables, address translation, and the hardware-software collaboration that enables modern multitasking. Understand TLBs, page faults, and memory protection.

Every process believes it has the entire machine to itself. It sees a vast, contiguous address space starting from zero, completely isolated from other processes. This illusion is virtual memory—one of the most important abstractions in computing. Understanding how operating systems and hardware collaborate to maintain this illusion reveals fundamental insights about performance, security, and system design.

1. The Need for Virtual Memory

Before virtual memory, programming was a constant juggling act.

1.1 Problems with Physical Addressing

Early systems used physical addresses directly:

Program A loads at address 0x1000:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 0x0000 │ 0x1000 │ 0x2000 │ 0x3000 │

│ OS │Program A │ Free │ Free │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Problems:

1. Relocation: Programs must know their load address

- Code compiled for 0x1000 won't work at 0x2000

- Must recompile or use position-independent code

2. Protection: Nothing stops A from accessing OS memory

- Buggy program can crash entire system

- Malicious program can read other programs' data

3. Fragmentation: Memory becomes unusable swiss cheese

┌────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┬────┐

│ OS │Free│ A │Free│ B │Free│ C │Free│

└────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┴────┘

Total free: 400KB, but largest contiguous: 100KB

4. Limited space: Programs limited to physical RAM

- 16MB RAM = 16MB maximum program size

- No way to run larger programs

1.2 Virtual Memory Goals

Virtual memory provides:

1. Isolation

Each process sees private address space

Process A's address 0x1000 ≠ Process B's 0x1000

2. Protection

Hardware enforces access permissions

Read-only code, no-execute data, kernel-only regions

3. Simplified programming

Every program links at same virtual address

Compiler doesn't need to know load location

4. Memory as abstraction

Virtual space can exceed physical RAM

OS pages data to disk transparently

5. Sharing

Multiple processes can map same physical page

Shared libraries loaded once, mapped many times

1.3 Address Space Layout

Typical 64-bit Linux process virtual address space:

0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF ┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │ ← Shared across all processes

0xFFFF800000000000 ├─────────────────────────────┤

│ (Unused/Guard) │

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ Stack │ ← Grows downward

│ ↓ │

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ Memory Mapped Region │ ← Libraries, mmap files

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ ↑ │

│ Heap │ ← Grows upward

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ BSS │ ← Uninitialized data

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ Data │ ← Initialized data

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ Text │ ← Program code

0x0000000000400000 ├─────────────────────────────┤

│ (Unmapped) │ ← Catch NULL derefs

0x0000000000000000 └─────────────────────────────┘

2. Pages and Frames

The fundamental unit of virtual memory is the page.

2.1 Dividing Memory into Pages

Virtual and physical memory divided into fixed-size blocks:

Virtual Address Space Physical Memory

(Pages) (Frames)

┌─────────────┐ Page 0 ┌─────────────┐ Frame 0

│ │ │ │

├─────────────┤ Page 1 ├─────────────┤ Frame 1

│ │ │ │

├─────────────┤ Page 2 ├─────────────┤ Frame 2

│ │ ──────────► │ │

├─────────────┤ Page 3 ├─────────────┤ Frame 3

│ │ │ │

├─────────────┤ Page 4 ├─────────────┤ Frame 4

│ │ ──────────► │ │

└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘

Page size is typically 4KB (4096 bytes)

Some systems support larger pages: 2MB, 1GB (huge pages)

2.2 Address Decomposition

A virtual address has two parts:

32-bit address with 4KB pages:

┌────────────────────┬────────────────────┐

│ Page Number │ Page Offset │

│ (20 bits) │ (12 bits) │

└────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

2^20 = 1M pages 2^12 = 4KB per page

Example: Virtual address 0x12345678

Binary: 0001 0010 0011 0100 0101 0110 0111 1000

Page Number: 0x12345 (top 20 bits)

Page Offset: 0x678 (bottom 12 bits)

Translation:

1. Look up page number 0x12345 in page table

2. Get physical frame number (e.g., 0xABCDE)

3. Physical address = frame number + offset

0xABCDE << 12 | 0x678 = 0xABCDE678

2.3 Why Fixed-Size Pages?

Advantages of fixed-size pages:

1. Simple allocation

- Any free frame can satisfy any page

- No external fragmentation

- Bitmap or free list tracking

2. Efficient swapping

- Swap page-sized chunks to disk

- Predictable I/O sizes

3. Hardware simplicity

- Page table entry size is fixed

- Address translation is bit manipulation

Disadvantages:

1. Internal fragmentation

- 4097 bytes needs 2 pages (wastes 4095 bytes)

- Average waste: half a page per allocation

2. Page table size

- Must map entire address space

- 4KB pages in 48-bit space = huge tables

Trade-off: Larger pages reduce table size but increase fragmentation

3. Page Tables

The data structure that maps virtual to physical addresses.

3.1 Simple Flat Page Table

Conceptually, a page table is an array:

Page Table for Process A:

┌─────────┬─────────────┬───────────────────┐

│ Index │ Frame Number│ Flags │

├─────────┼─────────────┼───────────────────┤

│ 0 │ 0x00123 │ Present, RW │

│ 1 │ 0x00456 │ Present, RO │

│ 2 │ --- │ Not Present │

│ 3 │ 0x00789 │ Present, RW, User │

│ ... │ ... │ ... │

│ 1M-1 │ 0xFFFFF │ Present, RW │

└─────────┴─────────────┴───────────────────┘

Problem: For 32-bit address space with 4KB pages:

- 2^20 = 1,048,576 page table entries

- Each entry ~4 bytes

- Page table = 4MB per process!

For 64-bit with 48-bit virtual addresses:

- 2^36 entries = 68 billion entries

- Completely impractical

3.2 Multi-Level Page Tables

Solution: Hierarchical page tables

Only allocate table portions that are actually used

Two-Level Page Table (32-bit x86):

Virtual Address: 0x12345678

┌──────────┬──────────┬────────────┐

│ Dir (10) │Table (10)│Offset (12) │

└──────────┴──────────┴────────────┘

0x48 0x345 0x678

Page Directory Page Table Physical Memory

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ Entry 0 │ │ │ │ │

├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤

│ ... │ │ │ │ │

├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤

│ Entry 0x48 │───────────►│ Entry 0x345 │────────►│ Frame │

├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤ ├─────────────┤

│ ... │ │ │ │ │

└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘

Benefits:

- Sparse address spaces need few page tables

- Unused regions don't need table entries

- Trade: Extra memory access per level

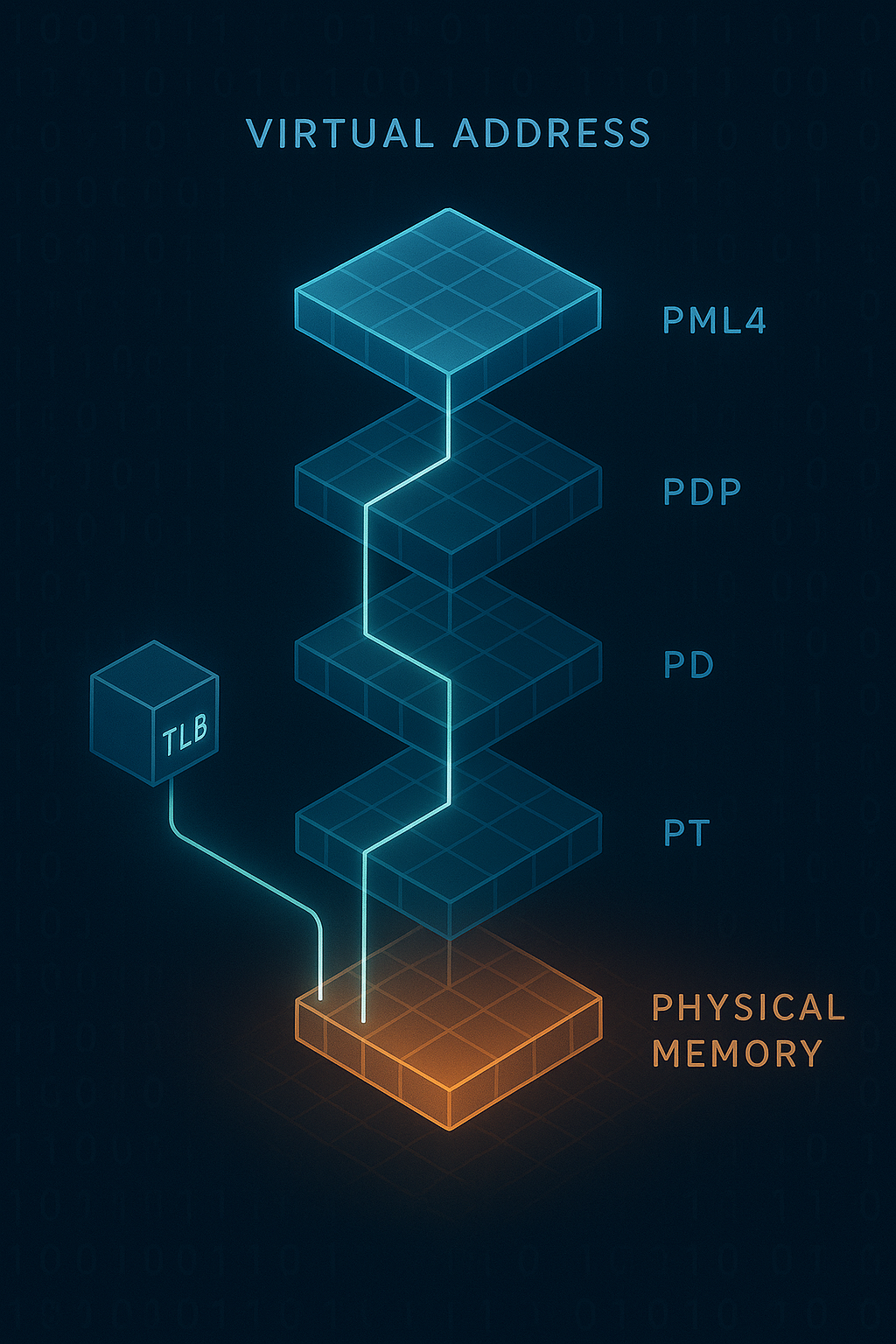

3.3 Four-Level Page Tables (x86-64)

Modern x86-64 uses 4-level paging (48-bit virtual addresses):

Virtual Address breakdown:

┌───────┬───────┬───────┬───────┬────────────┐

│PML4(9)│PDP(9) │PD(9) │PT(9) │Offset(12) │

└───────┴───────┴───────┴───────┴────────────┘

512 512 512 512 4096

Levels:

PML4 - Page Map Level 4 (512 entries)

└─► PDP - Page Directory Pointer (512 entries each)

└─► PD - Page Directory (512 entries each)

└─► PT - Page Table (512 entries each)

└─► 4KB Physical Page

Each entry is 8 bytes (64-bit pointers + flags)

Each table is 4KB (512 × 8 bytes = 4096)

Maximum addressable: 2^48 = 256 TB

Typical process uses tiny fraction of address space

3.4 Page Table Entry Format

x86-64 Page Table Entry (PTE):

Bit 63 Bit 12 Bit 11-9 Bit 8-0

┌──────────────┬───────────┬───────────┬────────────┐

│ NX │Reserved │Frame Addr │ Avail │ Flags │

└──────────────┴───────────┴───────────┴────────────┘

Key flags (bits 0-11):

Bit 0 (P): Present - page is in physical memory

Bit 1 (R/W): Read/Write - 0=read-only, 1=writable

Bit 2 (U/S): User/Supervisor - 0=kernel only, 1=user accessible

Bit 3 (PWT): Page Write-Through - caching policy

Bit 4 (PCD): Page Cache Disable

Bit 5 (A): Accessed - set by hardware on access

Bit 6 (D): Dirty - set by hardware on write

Bit 7 (PS): Page Size - 1=huge page (2MB/1GB)

Bit 63 (NX): No Execute - prevent code execution

Frame address: Physical frame number (bits 12-51)

4. Address Translation in Hardware

The CPU performs translation on every memory access.

4.1 Translation Process

CPU executes: mov eax, [0x12345678]

1. Extract page table indices from virtual address

PML4 index: bits 47-39 = 0

PDP index: bits 38-30 = 0

PD index: bits 29-21 = 0x91 (145)

PT index: bits 20-12 = 0x45 (69)

Offset: bits 11-0 = 0x678

2. Walk the page table hierarchy

CR3 register points to PML4 base address

PML4[0] → PDP base address

PDP[0] → PD base address

PD[0x91] → PT base address

PT[0x45] → Physical frame + flags

3. Check permissions

If not present → Page Fault

If user accessing kernel page → Page Fault

If writing read-only page → Page Fault

4. Compute physical address

Frame number from PTE + offset = physical address

4.2 Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

Problem: Page table walk requires 4 memory accesses per translation

Solution: Cache recent translations in TLB

TLB: Hardware cache of page table entries

┌─────────────────┬────────────────┬─────────────┐

│ Virtual Page # │ Physical Frame │ Flags │

├─────────────────┼────────────────┼─────────────┤

│ 0x12345 │ 0xABCDE │ RW, User │

│ 0x00001 │ 0x00042 │ RO, User │

│ 0x7FFFF │ 0x12345 │ RW, Kernel │

│ ... │ ... │ ... │

└─────────────────┴────────────────┴─────────────┘

TLB characteristics:

- Fully associative or set-associative

- Typically 64-1024 entries

- Split I-TLB and D-TLB common

- Hit rate > 99% for most workloads

TLB hit: ~1 cycle (included in memory access)

TLB miss: ~10-100 cycles (page table walk)

4.3 TLB Management

TLB must be kept consistent with page tables:

Context switch:

- New process has different page tables

- Old TLB entries are invalid

- Option 1: Flush entire TLB (expensive)

- Option 2: Tag entries with ASID (Address Space ID)

Page table updates:

- OS modifies page table entry

- Must invalidate corresponding TLB entry

- invlpg instruction on x86

TLB shootdown (multiprocessor):

1. CPU 0 modifies page table

2. CPU 0 invalidates local TLB entry

3. CPU 0 sends IPI to other CPUs

4. Other CPUs invalidate their TLB entries

5. CPU 0 waits for acknowledgment

Very expensive! Minimized by batching updates

4.4 Hardware Page Table Walker

Modern CPUs have dedicated page table walk hardware:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CPU │

│ ┌──────────┐ ┌───────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ Core │───►│ TLB │───►│ Page Table │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ Walker (PTW) │ │

│ └──────────┘ └───────┘ └─────────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ TLB Hit TLB Miss │

│ ▼ │ │ │

│ ┌──────────┐ │ ▼ │

│ │ Memory │◄────────┴───────────────┘ │

│ │Controller│ │

│ └──────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

PTW features:

- Runs in parallel with CPU execution

- Multiple outstanding walks possible

- Caches intermediate page table entries

- Can prefetch based on access patterns

5. Page Faults

When translation fails, the OS takes over.

5.1 Types of Page Faults

Page fault occurs when:

1. Page not present (P bit = 0)

2. Permission violation (write to RO, user to kernel)

3. Reserved bit violation

Fault types by cause:

Minor fault (soft fault):

- Page is in memory but not mapped

- Just update page table, no I/O

- Example: Copy-on-write page accessed

Major fault (hard fault):

- Page must be read from disk

- Significant latency (milliseconds)

- Example: Swapped-out page accessed

Invalid fault:

- Access to truly invalid address

- Results in SIGSEGV (segmentation fault)

- Example: NULL pointer dereference

5.2 Demand Paging

Pages loaded only when accessed:

Program starts:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Text │ Data │ BSS │ Heap/Stack │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

All pages marked "not present" initially

First instruction fetch:

1. CPU tries to read from text segment

2. TLB miss, page table walk

3. Page not present → Page fault

4. OS loads page from executable file

5. Maps page, marks present

6. Returns to instruction, retry succeeds

Benefits:

- Fast program startup

- Only load pages actually used

- Many code paths never executed

5.3 Copy-on-Write (COW)

Efficient process forking:

fork() without COW:

Parent: [Page A][Page B][Page C]

↓ copy all pages

Child: [Page A'][Page B'][Page C']

Problem: Expensive, child might exec() immediately

fork() with COW:

Parent: [Page A][Page B][Page C] ← Marked read-only

↘ ↓ ↙

Child: Shares same physical pages

When either process writes:

1. Page fault (writing to read-only page)

2. OS copies the page

3. Each process gets its own copy

4. Writing process page marked writable

Parent writes to Page B:

Parent: [Page A][Page B'][Page C] ← B' is new copy

Child: [Page A][Page B ][Page C] ← Still shares A and C

5.4 Page Fault Handler

// Simplified page fault handler logic

void page_fault_handler(fault_address, error_code) {

struct vm_area* vma = find_vma(current->mm, fault_address);

if (vma == NULL) {

// Address not in any mapped region

send_signal(current, SIGSEGV);

return;

}

if (!permissions_ok(vma, error_code)) {

// Permission violation

send_signal(current, SIGSEGV);

return;

}

if (is_cow_fault(vma, error_code)) {

// Copy-on-write

handle_cow(vma, fault_address);

return;

}

if (is_file_backed(vma)) {

// Memory-mapped file

page = read_page_from_file(vma->file, offset);

} else if (is_swap_backed(vma)) {

// Swapped out page

page = read_page_from_swap(swap_entry);

} else {

// Anonymous page (heap/stack)

page = allocate_zero_page();

}

// Map the page

map_page(current->mm, fault_address, page, vma->permissions);

}

6. Memory Protection

Virtual memory enables fine-grained access control.

6.1 Protection Bits

Each page has protection attributes:

Read (R): Can read from page

Write (W): Can write to page

Execute (X): Can execute code from page

Common combinations:

R--: Read-only data (constants, shared libraries)

RW-: Read-write data (heap, stack, globals)

R-X: Executable code (text segment)

RWX: Self-modifying code (JIT, avoid if possible)

User/Supervisor bit:

- U=1: User mode can access

- U=0: Kernel mode only

Protection prevents:

- Writing to code (code injection)

- Executing data (buffer overflow exploits)

- User accessing kernel memory

- Process accessing other process memory

6.2 Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)

Randomize virtual address layout for security:

Without ASLR (predictable):

Stack: 0x7FFFFFFFE000

Heap: 0x00602000

libc: 0x7FFFF7A00000

Binary: 0x00400000

With ASLR (randomized each run):

Run 1:

Stack: 0x7FFC12345000

Heap: 0x55A432100000

libc: 0x7F8901234000

Run 2:

Stack: 0x7FFD98765000

Heap: 0x562B87600000

libc: 0x7FA456789000

Makes exploitation harder:

- Attacker can't predict where things are

- Return-to-libc attacks need address leak

- Stack buffer overflows harder to exploit

6.3 Kernel Address Space Layout

Kernel/user separation:

Lower half (user): 0x0000000000000000 - 0x00007FFFFFFFFFFF

Upper half (kernel): 0xFFFF800000000000 - 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

Canonical address gap:

- Addresses 0x0000800000000000 - 0xFFFF7FFFFFFFFFFF invalid

- Hardware checks bit 47 is sign-extended through bits 48-63

- Provides 128TB user + 128TB kernel

KPTI (Kernel Page Table Isolation):

- Meltdown mitigation

- User page tables don't map kernel

- Switch page tables on kernel entry/exit

- Performance cost ~5% on syscall-heavy workloads

7. Swapping and Paging to Disk

Virtual memory can exceed physical RAM.

7.1 Page Replacement

When physical memory is full:

1. Select victim page to evict

2. If dirty, write to swap

3. Update page table (mark not present)

4. Use freed frame for new page

Page replacement algorithms:

FIFO (First In First Out):

- Evict oldest page

- Simple but ignores usage patterns

- Suffers from Belady's anomaly

LRU (Least Recently Used):

- Evict page unused longest

- Good approximation of optimal

- Expensive to implement exactly

Clock (Second Chance):

- Circular list of pages

- Check accessed bit, give second chance

- Approximates LRU cheaply

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ │

│ │ A │─►│ B │─►│ C │─►│ D │ │

│ │A=1│ │A=0│ │A=1│ │A=0│◄─┐ │

│ └───┘ └───┘ └───┘ └───┘ │ │

│ ▲ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────┘ │

│ Clock hand │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

7.2 Working Set Model

Working set: Pages actively used by process

Working Set Size over time:

│ ┌────────────┐

│ ┌──────────┐ │ │ ┌───────

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ └────┘ └────┘

└────┴─────────────────────────────────────────►

Phase 1 Transition Phase 2 Phase 3

Thrashing:

- Working set > available memory

- Constant page faults

- Process makes no progress

Detection:

- High page fault rate

- Low CPU utilization despite load

- Excessive disk I/O

Solutions:

- Reduce degree of multiprogramming

- Add more RAM

- Kill memory-hungry processes

7.3 Swap Space Management

Swap partition/file organization:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Swap Space │

├─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┤

│ P1 │Free │ P2 │ P1 │Free │ P3 │ P2 │Free │ P1 │

│pg 5 │ │pg 2 │pg 8 │ │pg 1 │pg 9 │ │pg 3 │

└─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

Swap entry in page table:

When page is swapped out, PTE contains:

- Present bit = 0

- Swap device/file identifier

- Offset within swap space

Linux swap organization:

- Swap areas (partitions or files)

- Priority ordering (faster swap first)

- Swap clusters for sequential I/O

- Frontswap for compressed memory

7.4 Memory Pressure Handling

Linux memory management:

Free memory watermarks:

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ High watermark ───────────────────────────── │

│ (comfortable, no action needed) │

│ │

│ Low watermark ───────────────────────────── │

│ (kswapd wakes up, background reclaim) │

│ │

│ Min watermark ───────────────────────────── │

│ (direct reclaim, allocations block) │

│ │

│ Out of memory ───────────────────────────── │

│ (OOM killer invoked) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Reclaim targets:

1. Page cache (clean file pages)

2. Dirty file pages (write back first)

3. Anonymous pages (swap out)

4. Slab caches (kernel allocations)

8. Memory-Mapped Files

Mapping files directly into address space.

8.1 mmap() System Call

// Map file into memory

int fd = open("data.bin", O_RDWR);

struct stat st;

fstat(fd, &st);

void* addr = mmap(

NULL, // Let kernel choose address

st.st_size, // Map entire file

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, // Read and write access

MAP_SHARED, // Changes visible to other processes

fd, // File descriptor

0 // Offset in file

);

// Now access file like memory

char* data = (char*)addr;

data[0] = 'H'; // Writes to file (eventually)

// Unmap when done

munmap(addr, st.st_size);

close(fd);

8.2 Private vs Shared Mappings

MAP_SHARED:

- Changes written back to file

- Changes visible to other processes

- Used for: IPC, shared databases

Process A: [Page]──┐

├──► Physical Frame ◄──► File on disk

Process B: [Page]──┘

MAP_PRIVATE:

- Changes are copy-on-write

- Changes NOT written to file

- Used for: Loading executables, private copies

Process A: [Page]──┐

├──► Physical Frame (COW)

Process B: [Page]──┘

│

▼ (after write)

[Page A']──► Different Frame (private copy)

8.3 Memory-Mapped I/O Benefits

Traditional read() vs mmap():

read() approach:

1. System call overhead

2. Copy from kernel buffer to user buffer

3. Sequential access pattern assumed

mmap() approach:

1. One-time setup cost

2. Zero-copy access (page table trick)

3. Random access efficient

4. Automatic caching via page cache

When to use mmap:

✓ Large files with random access

✓ Shared memory between processes

✓ Memory-mapping hardware devices

✓ Efficient file-backed data structures

When to use read/write:

✓ Sequential access patterns

✓ Small files

✓ Portability concerns

✓ Fine-grained error handling needed

8.4 Anonymous Mappings

Memory not backed by any file:

// Allocate 1GB of anonymous memory

void* mem = mmap(

NULL,

1UL << 30, // 1GB

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS,

-1, // No file

0

);

// Memory is zero-initialized (lazily)

// Pages allocated on first access

Uses:

- Large heap allocations (malloc uses for big allocs)

- Stack growth

- JIT compilation buffers

Backed by:

- Zero page initially (read)

- Anonymous frames on write

- Swap space if swapped out

9. Huge Pages

Larger pages for better performance.

9.1 TLB Pressure Problem

Standard 4KB pages:

- 1GB of memory = 262,144 pages

- TLB might hold 1024 entries

- TLB covers only 4MB

- High miss rate for large data

Huge pages (2MB):

- 1GB = 512 huge pages

- Same TLB covers 1GB

- Dramatically fewer misses

Huge pages (1GB):

- 1GB = 1 page

- Single TLB entry covers all

- Best for truly huge allocations

9.2 Transparent Huge Pages (THP)

Linux can automatically use huge pages:

Configuration:

/sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

[always] madvise never

always: System tries to use huge pages everywhere

madvise: Only where application requests

never: Disabled

Benefits:

- No application changes needed

- Reduced TLB pressure

- Less page table overhead

Drawbacks:

- Memory fragmentation can prevent huge pages

- Compaction overhead (khugepaged)

- Memory waste (internal fragmentation)

- Latency spikes during promotion/demotion

9.3 Explicit Huge Pages

// Using hugetlbfs

#include <sys/mman.h>

// Allocate 2MB huge page

void* huge = mmap(

NULL,

2 * 1024 * 1024,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_HUGETLB,

-1,

0

);

// Or using madvise

void* regular = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

madvise(regular, size, MADV_HUGEPAGE);

// Database use case: pre-allocate huge pages at boot

// Reserve: echo 1024 > /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages

// Mount: mount -t hugetlbfs none /mnt/huge

// Application maps files from /mnt/huge

9.4 Huge Page Trade-offs

Advantages:

+ Fewer TLB entries needed

+ Smaller page tables

+ Faster page table walks

+ Better for large contiguous data

Disadvantages:

- Memory fragmentation (need contiguous 2MB/1GB)

- Internal fragmentation (waste for small allocs)

- Longer page fault handling

- Copy-on-write copies more data

- Swapping granularity larger

Best for:

- Databases (large buffer pools)

- Scientific computing (large arrays)

- Virtual machines (guest RAM)

- In-memory caches

Avoid for:

- Small allocations

- Short-lived processes

- Memory-constrained systems

10. NUMA and Memory Locality

Non-Uniform Memory Access in multi-socket systems.

10.1 NUMA Architecture

Uniform Memory Access (UMA):

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ CPU 0 │ │ CPU 1 │

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │

└─────┬──────┘

│

┌─────┴─────┐

│ Memory │ ← Same latency from both CPUs

└───────────┘

Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA):

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────┐

│ CPU 0 │ │ CPU 1 │

└────┬────┘ └────┬────┘

│ │

┌────┴────┐ QPI/UPI ┌────┴────┐

│ Memory 0│◄─────────►│ Memory 1│

└─────────┘ └─────────┘

(local) (remote) (local)

~70ns ~120ns ~70ns

Local access: Fast

Remote access: Slower (cross-socket interconnect)

10.2 NUMA-Aware Allocation

// Linux NUMA API

#include <numa.h>

#include <numaif.h>

// Check NUMA availability

if (numa_available() == -1) {

// NUMA not available

}

// Allocate on specific node

void* local = numa_alloc_onnode(size, 0); // Node 0

void* remote = numa_alloc_onnode(size, 1); // Node 1

// Allocate interleaved across nodes

void* interleaved = numa_alloc_interleaved(size);

// Bind memory policy

unsigned long nodemask = 1; // Node 0 only

set_mempolicy(MPOL_BIND, &nodemask, sizeof(nodemask)*8);

// Migrate pages to local node

numa_migrate_pages(pid, &from_nodes, &to_nodes);

10.3 First-Touch Policy

Default Linux policy: First touch

Page allocated on node where first accessed:

// Thread on Node 0 allocates

char* data = malloc(1GB); // No physical pages yet

// Thread on Node 1 first touches

memset(data, 0, 1GB); // Pages allocated on Node 1!

// Thread on Node 0 accesses → remote!

Problem for parallel initialization:

// Main thread allocates

data = malloc(large_size);

memset(data, 0, large_size); // All on main thread's node

// Worker threads access → all remote!

Solution: Parallel first touch

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 0; i < size; i += PAGE_SIZE) {

data[i] = 0; // Each thread touches its portion

}

10.4 NUMA Balancing

Automatic NUMA balancing (Linux):

1. Periodically scan process memory

2. Identify pages accessed from wrong node

3. Migrate pages closer to accessing CPU

Implementation:

- unmaps pages periodically

- Page fault reveals accessing CPU

- Migration if remote access detected

Enable/disable:

echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/numa_balancing

Trade-offs:

+ Adapts to changing access patterns

+ No application changes needed

- CPU overhead for scanning

- Migration overhead

- May fight with application's own policy

11. Kernel Virtual Memory

How the kernel manages its own address space.

11.1 Kernel Address Space Layout

Linux x86-64 kernel memory layout:

0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF ┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Fixed mappings │ ← APIC, etc.

0xFFFFFFFFFE000000 ├──────────────────────────────┤

│ Modules │ ← Loadable modules

0xFFFFFFFFC0000000 ├──────────────────────────────┤

│ vmemmap │ ← Page descriptors

0xFFFFEA0000000000 ├──────────────────────────────┤

│ vmalloc space │ ← Non-contiguous allocs

0xFFFFC90000000000 ├──────────────────────────────┤

│ Direct mapping │ ← All physical RAM

0xFFFF880000000000 ├──────────────────────────────┤

│ (guard hole) │

0xFFFF800000000000 └──────────────────────────────┘

11.2 Direct Mapping

All physical RAM mapped linearly:

Physical: 0x00000000 0x00001000 0x00002000 ...

│ │ │

Virtual: 0xFFFF880000000000 ...

│ │ │

page_offset + phys = virt

Benefits:

- Simple physical ↔ virtual conversion

- All kernel data accessible without mapping

- Page tables themselves in direct map

Conversion macros:

__pa(virt) → physical address

__va(phys) → virtual address

phys_to_virt(phys) → virtual address

virt_to_phys(virt) → physical address

11.3 vmalloc Area

For large, non-contiguous kernel allocations:

kmalloc: Physically contiguous

vmalloc: Virtually contiguous, physically fragmented

Physical Memory: vmalloc Virtual Space:

┌───┐ ┌───────────────────┐

│ A │ │ ┌───┬───┬───┐ │

├───┤ │ │ A │ B │ C │ │

│///│ (used) │ └───┴───┴───┘ │

├───┤ │ Contiguous │

│ B │ └───────────────────┘

├───┤

│///│

├───┤

│ C │

└───┘

Use cases:

- Loading kernel modules

- Large buffers where contiguity not needed

- When physical memory is fragmented

Cost:

- Requires page table entries

- TLB pressure

- Slightly slower access than kmalloc

11.4 Kernel Memory Allocation

// Kernel allocation functions

// Small, physically contiguous

void* p = kmalloc(size, GFP_KERNEL);

kfree(p);

// Page-aligned, physically contiguous

struct page* page = alloc_pages(GFP_KERNEL, order);

void* addr = page_address(page);

free_pages(addr, order);

// Virtually contiguous (may be physically scattered)

void* v = vmalloc(large_size);

vfree(v);

// DMA-capable (specific physical constraints)

void* dma = dma_alloc_coherent(dev, size, &dma_handle, GFP_KERNEL);

// Slab allocator (object caching)

struct kmem_cache* cache = kmem_cache_create("my_objects",

sizeof(struct my_object), 0, 0, NULL);

struct my_object* obj = kmem_cache_alloc(cache, GFP_KERNEL);

kmem_cache_free(cache, obj);

12. Virtual Memory in Virtualization

Additional translation layers for virtual machines.

12.1 Shadow Page Tables

First-generation virtualization:

Guest virtual → Guest physical → Host physical

(Guest OS) (VMM)

Shadow page tables:

- VMM maintains shadow copies of guest page tables

- Shadow maps: Guest virtual → Host physical directly

- Guest page table changes trapped and synchronized

Guest Page Table: Shadow Page Table:

GVA → GPA GVA → HPA

┌─────┬─────┐ ┌─────┬─────┐

│ 0x1 │ 0xA │ │ 0x1 │ 0x50│

│ 0x2 │ 0xB │ ──────► │ 0x2 │ 0x51│

│ 0x3 │ 0xC │ │ 0x3 │ 0x52│

└─────┴─────┘ └─────┴─────┘

GPA → HPA mapping:

0xA → 0x50

0xB → 0x51

0xC → 0x52

12.2 Hardware-Assisted (Nested) Paging

Modern CPUs: EPT (Intel) / NPT (AMD)

Two levels of translation in hardware:

Guest Virtual Address (GVA)

│

▼ Guest page tables

Guest Physical Address (GPA)

│

▼ Extended/Nested page tables

Host Physical Address (HPA)

Benefits:

- No shadow page table maintenance

- Guest can modify its page tables freely

- Fewer VM exits

Costs:

- More levels to walk (up to 24 memory accesses!)

- Larger TLB entries (VPID + ASID)

- Still expensive on TLB miss

12.3 Memory Overcommitment

Giving VMs more memory than physically available:

Host has 64GB RAM

VM1: 48GB allocated

VM2: 48GB allocated

VM3: 48GB allocated

Total: 144GB > 64GB physical

Techniques:

1. Ballooning

- Balloon driver in guest "inflates"

- Guest OS pages out its own memory

- Host reclaims balloon pages

2. Page deduplication (KSM)

- Scan for identical pages across VMs

- Map to single physical page (COW)

- Common OS pages shared

3. Swap to host

- VMM pages out entire guest pages

- Guest unaware

- Poor performance if thrashing

4. Memory compression

- Compress cold pages in memory

- Faster than disk, saves space

13. Performance Considerations

Optimizing for virtual memory behavior.

13.1 TLB Optimization

Maximize TLB coverage:

1. Use huge pages for large data

Regular: 4KB × 1024 TLB entries = 4MB coverage

Huge: 2MB × 1024 TLB entries = 2TB coverage

2. Improve locality

- Access memory sequentially when possible

- Keep working set in as few pages as possible

- Avoid pointer chasing across many pages

3. Reduce context switches

- Each switch may flush TLB (without PCID)

- Batch work to reduce switches

4. Pin critical data

- mlock() to prevent swapping

- Ensures TLB entries remain valid

13.2 Page Fault Optimization

Minimize page faults:

1. Prefetch data

- madvise(MADV_WILLNEED) hints to kernel

- readahead() for file-backed mappings

2. Lock pages for real-time

- mlockall(MCL_CURRENT | MCL_FUTURE)

- Prevents any page-out, no major faults

3. Pre-touch memory

- Access all pages after mmap

- Takes faults upfront, not during critical path

4. Use MAP_POPULATE

- Pre-fault all pages at mmap time

- Slower setup, no faults later

// Pre-population example

void* mem = mmap(NULL, size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_POPULATE,

-1, 0);

13.3 NUMA Optimization

For NUMA systems:

1. Measure first

numastat # System-wide stats

numastat -p pid # Per-process stats

2. Bind processes to nodes

numactl --cpunodebind=0 --membind=0 ./app

3. Interleave for bandwidth

numactl --interleave=all ./bandwidth_heavy_app

4. Application-level awareness

- Query topology: numa_num_configured_nodes()

- Allocate per-thread data on local node

- Avoid false sharing across nodes

5. Monitor migrations

/proc/vmstat | grep numa

numa_hit, numa_miss, numa_foreign

13.4 Memory Bandwidth

Bandwidth bottlenecks:

Modern CPUs:

- Cache bandwidth: 100+ GB/s

- Memory bandwidth: 20-50 GB/s per channel

- Many-core chips can easily saturate memory

Optimization strategies:

1. Cache blocking / tiling

Process data in cache-sized chunks

2. Non-temporal stores

Bypass cache for write-only data

_mm_stream_si128() intrinsics

3. Memory-bound parallelism

More threads don't help beyond bandwidth limit

May hurt due to cache thrashing

4. Prefetching

Hide memory latency with lookahead

Hardware prefetch + software hints

14. Debugging Virtual Memory Issues

Tools and techniques for memory problems.

14.1 Process Memory Inspection

# Memory maps

cat /proc/PID/maps

7f8a12340000-7f8a12540000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 123456 /lib/libc.so.6

7f8a12540000-7f8a12740000 ---p 00200000 08:01 123456 /lib/libc.so.6

7f8a12740000-7f8a12744000 r--p 00200000 08:01 123456 /lib/libc.so.6

# Detailed memory stats

cat /proc/PID/status | grep -i mem

VmPeak: 1234 kB # Peak virtual memory

VmSize: 1200 kB # Current virtual memory

VmRSS: 800 kB # Resident set size

VmSwap: 100 kB # Swapped out memory

# Per-mapping details

cat /proc/PID/smaps

# Shows RSS, PSS, swap per mapping

# Page table stats

cat /proc/PID/pagetypeinfo

14.2 System Memory Analysis

# Overall memory

free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 15Gi 8.0Gi 2.0Gi 500Mi 5.5Gi 6.5Gi

# Detailed breakdown

cat /proc/meminfo

MemTotal: 16384000 kB

MemFree: 2048000 kB

MemAvailable: 6656000 kB

Buffers: 512000 kB

Cached: 5120000 kB

SwapTotal: 8192000 kB

SwapFree: 7168000 kB

Dirty: 12000 kB

AnonPages: 5000000 kB

Mapped: 1000000 kB

Shmem: 500000 kB

PageTables: 50000 kB

HugePages_Total: 0

HugePages_Free: 0

14.3 Page Table Analysis

# Page table overhead

grep PageTables /proc/meminfo

PageTables: 50000 kB

# Per-process page table size

cat /proc/PID/status | grep VmPTE

VmPTE: 5000 kB

# TLB statistics (requires perf)

perf stat -e dTLB-loads,dTLB-load-misses,iTLB-loads,iTLB-load-misses ./app

# Example output:

# 1,000,000,000 dTLB-loads

# 1,000,000 dTLB-load-misses # 0.1% miss rate

# 500,000,000 iTLB-loads

# 100,000 iTLB-load-misses # 0.02% miss rate

14.4 Common Problems and Solutions

High page fault rate:

- Check if swapping: vmstat 1

- Pre-touch memory: memset after mmap

- Use huge pages for large allocations

- Increase memory or reduce working set

TLB thrashing:

- Use huge pages

- Improve memory locality

- Reduce process count (fewer TLB flushes)

- Check for excessive mmap/munmap

NUMA imbalance:

- numastat shows hits vs misses

- Check thread-to-memory binding

- Consider interleaving for bandwidth workloads

Page table bloat:

- Large sparse address spaces waste page tables

- Consider madvise(MADV_DONTNEED) for unused regions

- Compact allocations when possible

OOM kills:

- Review overcommit settings

- Add swap space

- Set oom_score_adj for important processes

- Use cgroups memory limits

15. Advanced Topics

Cutting-edge virtual memory techniques.

15.1 Memory Tagging

ARM Memory Tagging Extension (MTE):

Each 16-byte granule has 4-bit tag:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Pointer: 0x1234_5678_9ABC_DEF0 │

│ Tag: ────────────────────0x5 │

│ │

│ Memory at 0x...9ABC_DEF0 has tag 0x5 │

│ Access with tag 0x5: OK │

│ Access with tag 0x3: Hardware exception! │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Use cases:

- Use-after-free detection

- Buffer overflow detection

- Memory safety without full bounds checking

Hardware support:

- Tags stored in memory (extra bits)

- Checked on every access

- Minimal performance overhead

15.2 Persistent Memory

Non-Volatile Memory (NVM):

byte-addressable persistent storage:

- Survives power loss like disk

- Accessed like memory (load/store)

- Latency ~100-300ns (between DRAM and SSD)

Programming model:

DAX (Direct Access) - bypass page cache

mmap() directly to NVM

Stores persist... eventually

Challenges:

- Cache flush ordering

- Atomic update guarantees

- Recovery after crash

// Persistent store pattern

store(data, address);

clwb(address); // Cache line write-back

sfence(); // Store fence

15.3 Heterogeneous Memory

Systems with multiple memory types:

Example: DRAM + NVM + HBM

- DRAM: Fast, expensive, volatile

- NVM: Slower, cheaper, persistent

- HBM: Fastest, very expensive

Tiered memory:

Hot data → Fast tier (DRAM/HBM)

Cold data → Slow tier (NVM)

Linux support:

- Memory tiering (kernel 5.14+)

- Automatic page migration

- NUMA-like node representation

Intel Optane / CXL memory:

- Attached via CXL interconnect

- Latency higher than local DRAM

- Capacity expansion use case

15.4 Memory Disaggregation

Future: Memory as network resource

Traditional:

┌─────────────────────┐

│ Server 1 │

│ CPU ←──► Memory │

└─────────────────────┘

Disaggregated:

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐

│ Compute Node │ ◄────► │ Memory Pool │

│ CPU only │ RDMA │ (shared) │

└─────────────────────┘ └───────────────┘

┌─────────────────────┐ ▲

│ Compute Node │ ◄───────────┘

│ CPU only │

└─────────────────────┘

Benefits:

- Independent scaling of compute/memory

- Better utilization (pool shared memory)

- Failure isolation

Challenges:

- Network latency in critical path

- Complex consistency models

- New programming models needed

16. Summary and Best Practices

Key takeaways for working with virtual memory.

16.1 Core Concepts Review

Virtual memory provides:

✓ Isolation between processes

✓ Protection (R/W/X permissions)

✓ Abstraction (address space > physical RAM)

✓ Sharing (libraries, copy-on-write)

Key mechanisms:

- Page tables map virtual → physical

- TLB caches translations

- Page faults handle on-demand loading

- Swap extends memory to disk

Performance factors:

- TLB coverage and hit rate

- Page fault frequency

- NUMA locality

- Cache behavior

16.2 Practical Guidelines

For application developers:

1. Understand your allocator

- Large allocations use mmap

- Small allocations from heap

- Consider jemalloc/tcmalloc for heavy allocation

2. Use huge pages for large data

- madvise(MADV_HUGEPAGE)

- Or MAP_HUGETLB explicitly

3. Consider NUMA on multi-socket

- First-touch placement matters

- Profile with numastat

4. Avoid excessive virtual memory

- Each mmap has overhead

- Don't map huge sparse ranges

5. Lock memory for latency-critical paths

- mlockall() or mlock()

- Prevents page faults in hot paths

For system administrators:

1. Monitor memory pressure

- Watch for swap usage

- Check for OOM events

2. Tune overcommit policy

- /proc/sys/vm/overcommit_memory

3. Configure huge pages appropriately

- Reserve at boot for guaranteed availability

4. Balance swappiness

- /proc/sys/vm/swappiness

- Lower for latency, higher for throughput

16.3 Debugging Checklist

When investigating memory issues:

□ Check overall memory usage (free, /proc/meminfo)

□ Examine process memory (pmap, /proc/PID/smaps)

□ Look for memory leaks (valgrind, AddressSanitizer)

□ Check page fault rates (perf stat)

□ Examine TLB behavior (perf stat TLB events)

□ Review NUMA placement (numastat)

□ Check for swap activity (vmstat, sar)

□ Look for OOM events (dmesg)

□ Verify memory limits (cgroups, ulimit)

Virtual memory is the foundation upon which modern operating systems build process isolation, memory protection, and the illusion of infinite memory. The collaboration between hardware page table walkers, TLBs, and operating system page fault handlers creates a seamless abstraction that programmers often take for granted. Yet understanding these mechanisms deeply enables you to write more efficient code, debug mysterious performance problems, and make informed architectural decisions. Whether you’re optimizing a database buffer pool, debugging a memory leak, or designing a new system, the principles of virtual memory inform every aspect of how programs interact with the machine’s most fundamental resource.